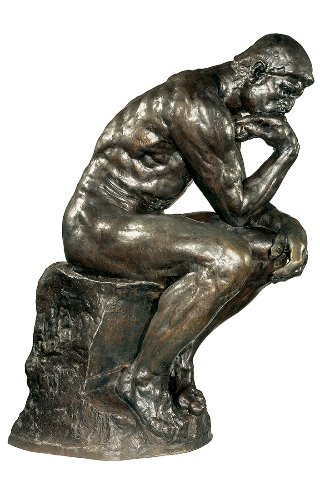

Rodin in the United States Confronting the Modern

Organized by the Clark Art Institute

By: Clark - Jun 09, 2022

While there has been much consideration of Auguste Rodin’s reputation in France and throughout Europe, less attention has been paid to his legacy in the United States. Organized by the Clark Art Institute, Rodin in the United States: Confronting the Modern, presents one of the largest Rodin exhibitions in the United States in the last forty years. Featuring some fifty sculptures and twenty-five drawings, including both familiar masterpieces and lesser-known works of the highest quality, the exhibition tells the story of the collectors, agents, art historians, and critics who endeavored to make Rodin known in America and considers the artist’s influence and reputation in the U.S. from 1893 to the present. Rodin in the United States is on view at the Clark Art Institute June 18 through September 18, 2022. The exhibition will then travel to the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia, where it will be on view from October 21, 2022 to January 15, 2023.

“This summer’s exhibition is an exciting opportunity for us to present a significant collection of many of Rodin’s most important sculptures and drawings and to share the story of the early years when his art was first being added to American museum collections” said Olivier Meslay, Hardymon Director of the Clark. “We will explore the ebb and flow of Rodin’s reputation over the last 125 years as the tastes of the time and curatorial interests evolved, and we will look at the influence of a fascinating group of Rodin’s supporters and critics. ”

The exhibition explores changing perceptions of the sculptor’s work, beginning with the first acquisition made by an American institution—the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1893—and Rodin’s controversial debut at Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition in the same year. The exhibition examines the collecting frenzy of the early twentieth century, promoted by noted philanthropist Katherine Seney Simpson, avant-garde performer Loïe Fuller, and collector Alma de Bretteville Spreckels. In the 1920s and 1930s many museums made important acquisitions of Rodin’s work, further fueling avid interest in the artist. By the 1940s and 1950s, the early enthusiasm had waned, and, in the words of art historian Leo Steinberg, Rodin’s reputation was “in full decline.” The exhibition further explores another shift in Rodin’s reputation in the 1980s that renewed the celebration of the artist which continues to the present day.

“The love story between Rodin and the United States, which first blossomed through the friendship between the artist and Katherine Seney Simpson, has never ended,” said Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, Rodin scholar and guest curator of the exhibition. “The United States is thus, after France, the country where Rodin is best represented in sculpture—terra cotta, plaster, marble, or bronze—as well as in drawing. The history of these collections, whether public or private, constitutes a history of taste whose vagaries form part of the history of modernity, represented in painting by the Impressionists, who we must not forget were Rodin’s contemporaries and some of whom, like Claude Monet, were his friends.” Le Normand-Romain is the former Director General of the National Institute of the History of Art in Paris and former curator at the Musée d’Orsay and Musée Rodin. She was the Edmond J. Safra Visiting Professor at the Center for the Advanced Study of the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. in 2016-17.

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

Auguste Rodin followed an unusual path to becoming one of the most innovative, influential, celebrated, and controversial sculptors of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Rejected at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, he studied instead at the Petite École, where copying traditional styles was promoted. For twenty years, he worked for jewelers, decorative artists, and masons. He honed his skill as a modeler of clay in other sculptors’ studios, taking evening art classes, and eventually setting up his own studio where he worked from live models.

Beyond literary, historical, and religious subjects, Rodin was interested in expressing human emotion. He often broke from convention by representing people around him, instead of models celebrated for their classical beauty. Some of Rodin’s sculptures looked unfinished to his contemporaries or bore the traces of his process. Rodin also went against academic standards that favored representations of the whole body posed in a traditional manner, choosing instead to focus on the fragment or partial figure in unexpected poses. Further, some pieces had no narrative framework while others expressed sexuality with an unapologetic frankness that was considered scandalous at the time.

Rodin first achieved a successful reception in the United States in the last decade of the nineteenth century and enjoyed a celebrated following for the next forty to fifty years. By the time of the Second World War, however, sentiment regarding Rodin’s art had shifted and his reputation suffered. His sculptures were either relegated to less prominent places in many museum collections or removed from the public eye. Tastes shifted again in the early 1980s following an important exhibition of his work at the National Gallery of Art, bringing about a resurgence of appreciation for Rodin in the United States that continues today.

Rodin in the United States: Confronting the Modern explores how American collectors have embraced Rodin’s sculptures and drawings over time, assembling collections and often giving them to public institutions to ensure more people could encounter Rodin’s revolutionary art. The highly researched show includes loans of key works by more than thirty museum and private collections from across the country.

Rodin’s reputation is firmly established in the United States today, but the path to his acceptance was a complicated, winding one, and the stories of the collectors and institutions who embraced his work reveal a desire to look beyond the conventional to confront—and embrace—the modern.

THE COLLECTORS

Rodin enjoyed success in Europe and England before American collectors and museums became interested. The first group of his sculptures was shown in the United States at the Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 and went largely unnoticed. Sara Tyson Hallowell (1846-1924), who lived in Chicago and worked as a curator and art advisor between Europe and America, was an early admirer of Rodin’s sculpture. She developed the “Foreign Masterpieces Owned in the United States” exhibition for the Department of Fine Arts at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition. Hallowell arranged for three Rodin marbles, including Cupid and Psyche (before 1883), to be shown in the Fine Arts Building at the international fair. The sensual quality of this work—a highlight of the Clark’s exhibition—was unexpected. Rodin’s entries were quickly judged too provocative and were moved into a private space that was only accessible by request. The Chicago Herald observed: “If such works were placed in the open of the sculpture corridors, they would have been brutally defaced.” As the Exposition progressed, however, the censorship garnered Rodin a notoriety that spurred public interest.

Rodin’s sculptures slowly began to enter private and public collections. Samuel Isham, a student at the Académie Julian in Paris from 1885 to 1887, was perhaps the first American to acquire one of Rodin’s marbles, Fallen Caryatid, now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and presented as part of the Clark’s exhibition. In 1893, collector Samuel P. Avery gifted The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bust of Saint John the Baptist (1888), making it the first Rodin sculpture to enter the collection of an American museum and setting a course of acquisition that would culminate in 1912 when the Metropolitan opened its Rodin Gallery.

The exhibition details the intriguing confluence of Rodin enthusiasts and the roles these influential collectors played in generating interest in his art from the late nineteenth century to today. Among them:

KATHERINE SENEY SIMPSON

Katherine Seney Simpson (1868-1943) was an important early advocate of Rodin’s work in the United States. In 1902, she and her husband, John Woodruff Simpson, met Rodin through a dealer and visited his Paris studio, where Katherine began posing for a portrait bust. The Simpsons bought bronzes, marbles, and drawings from Rodin for their own collection, and encouraged friends and museums to acquire his work as well. Simpson urged sculptor Daniel Chester French, chair of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Committee on Sculpture, to acquire Rodin’s work for the museum’s collection. The Metropolitan’s early interest resulted in the establishment of the first gallery in its history dedicated to a living artist, positioning the museum as a major repository of Rodin’s work in the United States. Although she was instrumental in helping to develop the Metropolitan’s Rodin collection, Simpson donated her own collection to the newly formed National Gallery of Art upon her death, bringing Rodin to a new audience, and helping to launch modern sculpture as a collecting priority at the museum.

LOÏE FULLER

American actor, dancer, and choreographer Loïe Fuller (1862-1928)—who pioneered modern, symbolist dance with billowing fabrics and theatrical lighting—became friends with Rodin while living and performing in Paris in 1900. She served as an agent for the artist, promoting his drawings and sculptures through exhibitions in New York (1903) and Cleveland (1917), as well as offering works to collectors. Fuller donated Rodin sculptures to the Cleveland Museum of Art and facilitated sales to West Coast collectors, including Alma de Bretteville Spreckels and Samuel Hill.

ALMA DE BRETTEVILLE SPRECKELS

Alma de Bretteville Spreckels (1881-1968), a wealthy philanthropist and heir to a sugar fortune, was an important collector of Rodin’s sculptures. She loaned and later donated sculptures to the Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco. (She and her husband also gave the museum building to the city.) Among the masterpieces Spreckels gifted to the Legion of Honor were bronzes such as The Prodigal Son (cast 1914) and Fallen Angel (cast probably 1915), as well as the remarkable portrait bust of Rodin by his contemporary, Camille Claudel, all featured in the exhibition.

SAMUEL HILL

Samuel Hill (1857-1931), a businessman and railroad executive who promoted development in the Pacific Northwest, founded the Maryhill Museum in Goldendale, Washington in 1926, donating more than eighty Rodin sculptures and drawings to the museum, including the exquisite sketch after Michelangelo’s Apollo sculpture, which Rodin encountered in Florence in 1876.

JULES MASTBAUM

Jules E. Mastbaum (1872-1926) opened his first movie theater in 1911 and over the next fifteen years, created the world’s largest theater chain. He may have encountered Rodin’s work in exhibitions and collections in his native Philadelphia, but a visit to the Musée Rodin in Paris in 1924 confirmed his passion. From that moment, he was determined to share his profound fascination with Rodin’s sculptures and drawings with others by assembling a significant collection. The monumental bronzes Mastbaum acquired—The Gates of Hell and The Burghers of Calais—showed his interest in Rodin’s important commissions as well as in works that revealed the artist’s debt to the sculpture of the Italian Renaissance. He displayed his collection at the Sesquicentennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1926 and began plans to create an independent museum on the city’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Although he died before his vision was realized, his wife and daughters continued his work and opened the Rodin Museum as a gift to the City of Philadelphia in 1929. Several works acquired by Jules Mastbaum as well as his wife Etta Mastbaum are in the exhibition.

- GERALD AND IRIS CANTOR

B. Gerald Cantor (1916-1996) became interested in Rodin after seeing a marble Hand of God (carved 1907)in New York in 1945. He began collecting, and later, with his wife Iris (b. 1931), formed a foundation through which they donated pieces by Rodin to institutions including the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for the Visual Arts at Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, which holds an encyclopedic collection of Rodin bronzes, particularly objects cast after Rodin’s death. The Cantors were keen to see Rodin’s work circulate widely, and to that end, supported the Musée Rodin’s efforts to produce posthumous bronzes, including the monumental Gates of Hell; the fifth bronze version of this portal was cast in 1981 for display at the National Gallery of Art’s Rodin Rediscovered exhibition, and is now part of the Cantor Arts Center’s collection. On display in this exhibition is the Cantor Arts Center’s The Age of Bronze (cast c. 1910–20), one of Rodin’s important early career works, as well as the posthumous bronze of Dance Movement H (cast 1965).

THE ERA OF MUSEUMS, 1917–1954

After Rodin’s death in 1917, a new generation of collectors discovered they could turn to the Musée Rodin to acquire newly cast bronzes. Rodin left the entire contents of his studio to the French state, under the condition that a museum dedicated to his art would be founded in the Hôtel Biron in Paris, a portion of which he had rented since 1908. Opened in 1919, the Musée Rodin had instruction from the artist to cast additional bronzes of his sculptures from clay and plaster models, in particular when they had never been cast before, as with the Gates of Hell. Casts had no limit during Rodin’s lifetime, but since the 1960s each model has been restricted to twelve bronze copies. By permitting these casts, the museum’s operations could be funded, and the addition of the works would further contribute to knowledge of Rodin’s art. Many collectors, including Jules Mastbaum and, later, the Cantors worked directly with the Musée Rodin to acquire bronzes of Rodin’s sculptures, which, through their philanthropy, then became part of public U.S. collections. A selection of posthumous casts is on view in the exhibition, including the unique cast of Shame (Absolution) (cast 1925–26, Rodin Museum/Philadelphia Museum of Art), ordered by Mastbaum after he encountered the plaster in storage at the Musée Rodin.

While U.S. museums expanded their holdings of Rodin by gift and purchase during this period, many institutions tended to display his more finished, narrative subjects. A majority of the seemingly unfinished, fragmented, or more “erotic” works—appreciated today for their daring and modernity--were consigned to storage, where they languished for years until after the Second World War when a “new” Rodin appeared.

THE REVIVAL, 1954—TODAY

In the 1940s, Rodin fell out of favor with avant-garde artists, critics, and curators. Some museums put their Rodin bronzes and plaster fragments in storage. Rodin’s more abstract sculptural forms and experimental drawings were hidden from public view, unrecognized for their powerful modernism.

In 1954, Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, requested a bronze cast of Rodin’s Monument to Balzac for the museum’s collection. Barr considered Balzac one of the greatest sculptures in the history of Western art. From that moment, scholars and critics began a reappraisal of Rodin’s works, culminating in exhibitions like the National Gallery of Art’s Rodin Rediscovered in 1981, and a host of new books that made Rodin more accessible to the public, while highlighting all aspects of his production. MoMA’s Monument to Balzac is presented in a special installation in the Clark’s Conforti Pavilion as part of the exhibition.

A 2011 exhibition at the Cantor Arts Center, Rodin and America: Influence and Adaptation, 1876–1936, studied early interest in the artist by American museums and his influence on younger American artists. Rodin in the United States: Confronting the Modern expands upon the critical precedent set by the Cantor Arts Center exhibition by bringing together a broad representation of acquisitions of the artist’s sculptures and drawings made by U.S. museums and collectors from 1954 to today, bringing consideration of Rodin’s work full circle for current audiences. The richness and variety on view demonstrates that Rodin’s reputation as an innovative and influential sculptor and draftsman is fully established in the United States.

Rodin in the United States: Confronting the Modern is organized by the Clark Art Institute and guest curated by independent scholar Antoinette Le Normand-Romain with the collaboration of Christina Buley-Uribe, an expert on Rodin’s drawings. The Clark’s curatorial team, including Esther Bell, Robert and Martha Berman Lipp Chief Curator, Alexis Goodin, curatorial research associate, and Kathleen Morris, Sylvia and Leonard Marx Director of Collections and Exhibitions, worked closely with Le Normand-Romain to develop the project for presentation at the Institute.

This exhibition is made possible by Denise Littlefield Sobel and Diane and Andreas Halvorsen. Major funding is provided by the Acquavella Family Foundation, with additional support from Jeannene Booher, Robert D. Kraus, the Robert Lehman Foundation, Carol and Richard Seltzer, and the Malcolm Hewitt Wiener Foundation. This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

A full slate of public programs, including curatorial lectures, dance performances, artist conversations, sandcasting and drawing workshops, and gallery tours will be offered throughout the run of the exhibition; details are available at clarkart.edu/events.

The exhibition also marks the publication of Rodin in the United States: Confronting the Modern, a 256-page catalogue edited by Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, with contributions by Christina Buley-Uribe, Patrick R. Crowley, C. D. Dickerson, Laure de Margerie, Veronique Mattiussi, Elyse Nelson, Jennifer A. Thompson, and Nora M. Rosengarten. The book is published by the Clark and distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven.

ABOUT THE CLARK

The Clark Art Institute, located in the Berkshires of western Massachusetts, is one of a small number of institutions globally that is both an art museum and a center for research, critical discussion, and higher education in the visual arts. Opened in 1955, the Clark houses exceptional European and American paintings and sculpture, extensive collections of master prints and drawings, English silver, and early photography. Acting as convener through its Research and Academic Program, the Clark gathers an international community of scholars to participate in a lively program of conferences, colloquia, and workshops on topics of vital importance to the visual arts. The Clark library, consisting of more than 285,000 volumes, is one of the nation’s premier art history libraries. The Clark also houses and co-sponsors the Williams College Graduate Program in the History of Art.

The Clark, which has a three-star rating in the Michelin Green Guide, is located at 225 South Street in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Its 140-acre campus includes miles of hiking and walking trails through woodlands and meadows, providing an exceptional experience of art in nature. Galleries are open 10 am to 5 pm Tuesday through Sunday, from September through June, and daily in July and August. Advance timed tickets are recommended. Admission is $20. Admission is also free on a year-round basis for Clark members, all visitors age twenty-one and under, and students with a valid student ID. Free admission is available through several programs, including First Sundays Free; a local library pass program; and EBT Card to Culture. For more information on these programs and more, visit clarkart.edu or call 413 458 2303.

Visitors age five and older are required to show proof of COVID-19 vaccination prior to entering the Clark’s facilities. Face masks are optional. For details on health and safety protocols, visit clarkart.edu/health.