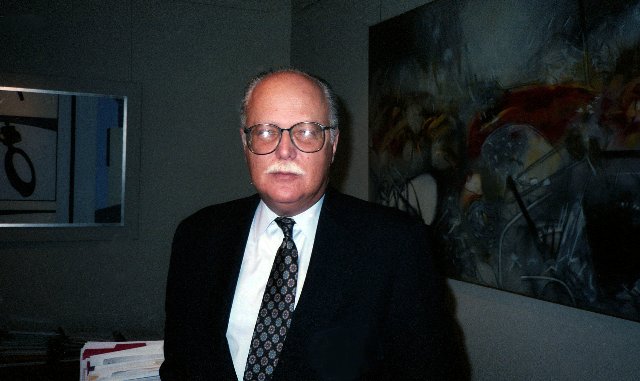

Former MFA Director Alan Shestack

Served from 1987 to 1993

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 11, 2020

On April 14, 2020 Alan Shestack passed away at 81. From 1987 to 1993 he was director of the Museum of Fine Arts. He was notable as a mediator and problem solver. As director he presided over 26 departments with an uneven distribution of resources and power.

There were highlights like the blockbuster 1990 Monet exhibition. A priority was support for contemporary art. An early hire was Kathy Halbreich to head the contemporary department. She left to become director of the Walker Art Museum where she remained for 16 years. He supported The Binational: German and American Art in the Late ‘80s a collaboration with the Institute of Contemporary Art. Shestack raised some $600,000 for the programming of Trevor Fairbrother who took over from Halbreich.

By the end of his tenure Shestack was contending with an economic downturn. He sought creative strategies to monetize the museum. This partly entailed establishing a twenty-year relationship to show a range of works from the MFA in Nagoya, Japan.

Ted Stebbins, who was the MFA’s John Moors Cabot curator of American paintings while Shestack was director, said in a museum statement that “Alan was one of the finest people I have ever known. A superb scholar, a lover of all kinds of art, a person of the highest integrity, he also had a terrific sense of humor.”

During an inaugural address in 1987, Shestack described how the elitist Medici era of museums was over. To upgrade and mdernise the museum entailed bricks and mortar espansion. There were projects for new galleries, retail and expanded dining facilities. Permanent collection galleries were climate controlled, renovated and reinstalled. It was no longer possible for board members to write end of the year checks to balance the books. Admission fees represents 20% of the actual cost per visitor.

Much of this had been initiated prior to his arrival. There was systemic instabity and rapid turnover of two directors following the scaandal that ended the long ternure of Perry T. Rathbone.

Shestack told me that he felt like he had jumped onto a fast moving express train. By the end of his six year term, bucking an economic downturn, that engine had lost momentum.

In his first remarks to an MFA audience he recalled early days, through graduate school, of quiet contemplation in galleries. Museum work was long regarded as a genteel profession for directors and senior curators. Museums attracted the wealthy and educated. There was limited impulse to educate visitors or explain works on view.

As museums expanded and became more expensive there was a paradigm shift. That entailed more outreach and fundraising. Conservative critics like Robert Hughes and Hilton Kramer deplored populism and commercialization. They lamented the passing of the good old days. Shestack noted that community outreach started with the Philadelphia Museum.

“Detroit, with a dominantly black community, came to realize that it needed a collection of African art” he told the audience. “The hope was that groups of school children who came to the museum would relate to that work. In order to understand it they would want to know more about it. They would be more interested in that than say a portrait of George III. Last year, in Minneapolis, I urged the acquisition of a very handsome Shoshone elk hide with pictographs, because Minneapolis sits in the largest concentration of Plains Indians in North America. I felt that we needed not just one object but many in the museum that Indian children could relate to. You couldn’t bring in a group of Indian children from a reservation and just show them Italian baroque paintings. There are legitimate reasons for doing this.”

If Shestack came to the museum with hopes of diversity there were mixed results. He fought for change but encountered resistance. As the Globe reported in his obituary “I do not choose the board, of course; they choose me,” he told the Globe in January 1991. “But I have certainly let them know my feeling that the board is a little homogenized.”

“Nearly all the museum’s department heads were white then as well. In the same interview, for a Globe report on the lack of diversity in the museum’s staffing and holdings, Mr. Shestack noted that change occurs slowly at institutions steeped in tradition.

“We haven’t been in the vanguard, I’m sad to say. But finally, museums are getting a little social conscience,” he said, adding with a note of frustration: “I am a member of the American Civil Liberties Union. It’s hard to be a liberal and lead an institution like this.”

What follows was the first of several interviews. This occurred in 1987 when he was new to the position. We will also transcribe and post an interview from 1991.

Charles Giuliano I attended your inaugural address. Can we pick up from there with an overview of coming to the museum at this time?

Alan Shestack The truth is very hard to define. Everyone has a different version of the past and any particular instance that has occurred. I’m not really sure I know the recent history of this museum in specific terms. I know where it stands at this moment. I’m not quite sure I know how it got to where it is. Who made certain decisions or why?

There has been a recent spate of articles criticizing the museum. There was one three weeks ago. It seems that my arrival has been accompanied by a series of critical articles. They seem to be digging up problems of the past. Including things that Walter Whitehill (1905-1978) said fifteen or twenty years ago but not stating that he said them fifteen or twenty years ago. As far as the reader is concerned, they may have been uttered recently. It’s a bit unfair in that respect.

(Whitehill was director of the Boston Athenaeum and a trustee. He was a prolific writer including Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: A Centennial History Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 1970.)

The media is critical of the traditional, elitist image of the museum. I told my staff that unlike Ronald Reagan, who was described as a Teflon President, we seem to be The Velcro Museum.

Problems that were legitimate fifteen or twenty years ago no longer are but stick because of the museum’s reputation. Opinions lag reality for quite a long period because frankly I have not, in my very short tenure here, but also in my negotiations with the board when I was deciding if I wanted to come to this job, I have not sensed any elitism in terms if keeping anyone out of the museum or keeping the board pure. I have not sensed that at all.

I find the board here to be very much in line with boards of other major American museums. Its diversity, or lack thereof, is very much in line with how it is in most museums. Typically, trustees are people with money, civic pride, and jobs that allow them a lot of free time. As it is with most museums, I do not find the board in any way unusual.

As it is for every museum director in this country, there is an attempt for a proper balance between traditional values of art museums, and the new initiatives that museums have taken. Maintaining our integrity is going to be a tricky business.

For these initiatives we have to find money because these museums are so expensive. The admission fee to this museum is admittedly a bit on the high side at $5 a ticket. The admissions pay for only a fifth of what it actually costs to run the museum. In other words, each visitor who walks through the door costs us $25. You derive that by taking the number of visitors and dividing into the annual budget.

(The museum is closed because of Covid-19. Until then, and when it resumes, adult admission is $25.)

Compared to other major museums we get no money from the city, unlike The National Gallery, Met, Philadelphia, and Art Institute of Chicago. They all get substantial subsidies from their cities. This museum does not.

CG I believe the city helps to fund the program to bus school children to the museum. (Then $60,000 annually,)

AS I wasn’t aware of that. To be fully honest the Mass Council for the Arts and Humanities has been very generous of late and that has been very heartening. When I walked through the door the first thing I heard was a grant from them ($300,000) for the German show we are doing next year (with the ICA American and German Art of the Late 80’s: The Binational.)

Compare that to $13 million a year the Met gets from New York City.

CG What’s the annual budget of the MFA?

AS $26 million. We have to find that money. Marketing is part of the American way of life. But if we do it that has to be done with integrity. We have to look at the quality of what we sell in the shop. I went down to the shop the other day and didn’t see anything objectionable.

If I may criticize your profession for a moment, you look for cute things to say, or a handle to hang an article on. There was that comment on Howard Johnson (board president) and cats. He didn’t get it. Selling cats in the shop? I wonder if we should look for unpopular things to sell in our shop. What’s wrong with Winslow Homer greeting cards?

The other side of this is if the museum never got into the retail business. Improving its restaurant and building the (West) wing. What if the museum were just the way it was twenty years ago? If we continued in that way, I am pretty sure the press would be criticizing us for not taking any initiative. Not taking ways to balance our budget. Half or our galleries would be dark because we didn’t have the money to pay enough guards.

No matter which direction we took there would be room for criticism. This museum finally got on the bandwagon in the past fifteen or twenty years, and began to think about how do we survive into the 21st century? You can’t do it the old way anymore. That speaks well for this museum.

CG I understand and don’t have a problem with that. I have programming concerns. What was the motivation for showing a corporation like Tiffany?

AS Tiffany has been a very classy company over the years and has employed the best designers. It’s been at the forefront of design experimentation. We justify the exhibition based on the quality of the objects in the show. The fact that they were produced to be sold by a store, rather than an individual artist, is not an issue. I have no idea how it was decided to have that show. It was installed when I got here.

CG I understand that the Met turned it down.

AS That would have no impact on me. What they do makes no difference to decisions that we make. The National Gallery and Detroit chose to have it as did San Francisco and I think Dallas. There were plenty of museums that chose to have it. I don’t want to second guess my predecessors.

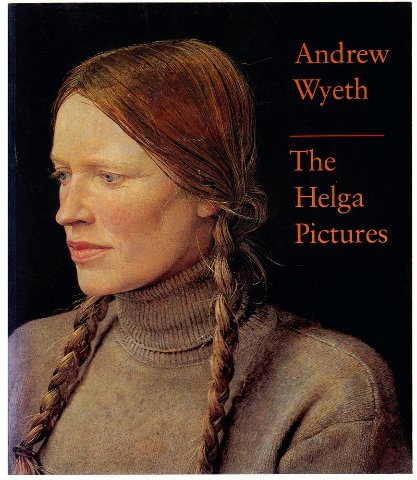

Let me say this though about Helga. It’s ironic that the MFA has been criticized for being stodgy and elitist but the minute that it does a show that is bound to have a large audience, because it presents a beloved artist of the people, then we get accused of pandering to the public.

It can’t go both ways. Either we’re doing something useful for the public’s good. Indeed, a show that is bound to be mighty popular and we’re not stodgy. Or we’re stodgy for not doing that kind of show. We get criticized from both directions at the same time. I have mixed feelings about Andrew Wyeth: The Helga Pictures (1987).

There have been Wyeth works in museums that I have found very impressive. The jury is still out on Helga. The avant-garde critics regard Wyeth as sentimental and anecdotal. If you’re an Ellsworth Kelly person you’re not going to find Helga attractive.

I’m not sure that it’s wrong, for a museum such as this one, that’s desperately trying to shed its old, outdated, elitist image to put on a show from time-to-time that most people will like.

CG You mentioned a Monet show.

AS We’re working on one. I hate to mention it because we haven’t negotiated and committed to it yet. There’s a possible show of Leonardo DaVinci drawings. It’s a show we would pull from the collection of Windsor Castle. We’re not going to know for a year or so if it’s OK or not.

CG Who initiated it?

AS The director of the Houston Museum. It’s a show of anatomical drawings by Leonardo. Given Boston’s importance in medicine it would be a wonderful show for us to have. Given the fame of Leonardo it would be a big drawing card.

If you were to ask me whether I would prefer to have Leonardo da Vinci or Andrew Wyeth the answer is clear. People would turn out in great numbers without a doubt.

CG Can you give me some other examples?

AS I will have to look in the book and see what’s coming up. I have been here such a short time that I haven’t had an influence on those decisions yet. My first exhibitions meeting is next week.

We have some shows planned which are not what you call blockbusters. You shouldn’t get the impression that all that happens in this museum is a season of blockbusters. We try to have a nice mix. We’re having Ellsworth Kelly. We’re doing much more with contemporary art.

This winter we’re doing a show of 17th century Dutch landscapes that Peter Sutton has been working on from the moment he got here. People will love the show if they give it a chance. It has Jacob van Ruisdael and all the great landscape painters of that era. But it’s not a show with a sexy title and household name quality. We don’t know what kind of public response we will get. We can take chances like that and throw into the mix something that’s going to help us make it through the year.

If Helga brings people in it helps us to do the scholarly shows we have an obligation to present. We are not able to find a corporate sponsor for the Dutch show, yet we are able to do it, and have our fingers crossed.

(The influence of Sutton and that exhibition proved to be palpable. In 2017 the museum announced a major acquisition of two collections that include 113 works by 76 artists. The gifts represent the largest donation of European paintings to the MFA and nearly doubled the museum's holding of Dutch and Flemish paintings. Boston-area collectors Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo and Susan and Matthew Weatherbie began collecting Netherlandish work in the '80s. Rose-Marie van Otterloo said Peter Sutton, a former curator of European art at the MFA, encouraged her and her husband to focus on collecting this genre.)

We’re having a show of Charles Sheeler’s photography from the Lane Collection. For me that represents the perfect show. We have staff members with great expertise. The show makes a point with a two-volume catalogue. It’s the last word on Sheeler with complete assessment and reappraisal. It’s the biggest show of this work ever mounted and Sheeler is just famous enough that people will want to see it. At the same time, it serves a scholarly function. It’s the kind of thing I like to see happen.

We have a Goya show for 1989. Our curator, Eleanor Sayre, is one of the great Goya scholars. It’s paintings, prints and drawings. It’s coming from all over with thirty or forty lenders. It opens in Madrid then comes to Boston and New York.

We have the Fitz Hugh Lane show (now Fitz Henry Lane) which Ted (Stebbins) wants to do. But Lane is not a household name. That will be coming here in ’88. It’s a show I’m very excited about but not sure it will attract crowds.

We are collaborating with David Ross and the ICA, and Jurgen Harten for Germany, on a show that we are organizing of avant-garde American and German art. Half will be at the ICA and half will be here. (The Binational: American Art of the Late 1980s and German Art of the Late 1980s) The museum in Dusseldorf will be organizing a show of avant-garde German art. When the shows end, they will then exchange. We’ll have the German show and they’ll have the American show. Younger staff members of both institutions are involved in the selection of the art.

(Trevor Fairbrother for the MFA with Elizabeth Sussman and David Joselit for the ICA. The project evolved from a global colloquium organized by the ICA and funded by Ann Hawley and the Mass Council which contributed $300,000 to The Binational. Harten participated in the colloquium and pitched the idea to Ross who expanded to the MFA through curator Ted Stebbins and director Jan Fontein. Shestack inherited and saw through the project.)

I don’t know how Boston will react. It’s very experimental. Many of the artists will create works for the exhibition. That’s why the deadline for the catalogue is held to the very last second. It’s expensive with a lot of complex logistics but an exciting idea. Of course, I had nothing to do with the planning of the project.

(The curators jointly made studio visits in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Texas and New York. It was decided not to follow a Whitney Biennial formula with a mix of established and emerging artists. There was a decision not to seek geographic distribution. The focus was on the most impactful art of that moment. The artists included: Ross Bleckner, St. Clair Cemin, Constance DeJong, Tim Ebner, Karen Finley, Robert Gober, Peter Halley, Connie Hatch, Tishan Hsu, Mike Kelley, Jeff Koons, Tony Labat, Annette Lemieux, David McDermott and Peter McGough, Tony Oursler, Stephen Prina, Richard Prince, Tim Rollins + K.O.S., Lorna Simpson, Doug and Mike Starn, Haim Steinbach, Philip Taaffe, Meyer Vaisman, Meg Webster, James Welling, and Christopher Wool.)

I just signed a letter of commitment to a show of Ancient Greek bronzes from American collections. It will be us, Cleveland, and another museum.

We are doing a lot of scholarly shows. The mix is good. Over the next two years here the museum will provide something for every taste. To be judged solely on accepting Helga for 1987 would be a very unfair thing. Helga is controversial and that’s interesting.

In the November calendar which is going out to members I say “Come see Sheeler one of the great American photographers, and, while you’re here take a peek at the Helga show and judge for yourself.”

CG It will take some time before you have an impact on the exhibition schedule.

AS It won’t be until 1990.

CG As said before there has been a period of growth and change. What shape do you find the museum in now? There has been enormous renovation. Do decorative arts come next?

AS I’m not sure what comes next. There’s renovation pending for classical, Egyptian, European and American decorative arts.

CG Completing renovation of Evans Wing of Paintings and the Asiatic Wing gives a false impression that the work has been done.

AS That’s a tremendous start. The other day I said to the board it feels as though I have leaped onto a fast-moving train. My job here will be to access what’s going on. It’s a little too soon to say. Around Christmas I will have enough of a handle to make strong recommendations.

CG Will you be a bricks and mortar director?

AS That will be determined by what’s needed most. I’ll probably be a little of everything. I don’t think I categorize myself easily. I enjoy every aspect of museum work. I’m interested in what’s going on in the education department. I’m a part of the reassessment which is in full swing now. I’ll look at our space needs. Every curator wants more space.

Between now and Christmas, I’m spending two or three hours with each department. I’ve made 26 appointments. I plan to spend one or two hours with each. The other day it turned into five hours. I had a 2:30 appointment and thought I would be back in the office by five. I was there until 7:30. I learned everything I needed to know about that department.

Over the coming months I have so many things to cope with that I can’t do it all at once. When I have made all of those individual calls, only then will I be able to sit down and draft a state of the museum message.

Between now and then I’m going to have to make decisions on an ad hoc basis.

CG When you were negotiating for the position you likely had overall impressions of the institution. What did you feel you might achieve and why were you the right person for the tasks at hand?

AS From a distance my impression was that it was at the cutting edge of the problems we are talking about. If you were looking for a museum that was struggling with the issues of the day you couldn’t find a better case study than the MFA. The museum has a great professional staff.

Two things made me want to be here. The collection. Most people don’t sense to what extent a curator or director feels attached to a collection and enjoys the job even if it is full of other problems, financial and political. If the collection is great it makes up for a lot of other problems.

I knew the collections here. Not intimately, there were parts I hadn’t looked at in depth. But I had a sense of the greatness of the collections.

That was number one. Then the curatorial staff is one of the best in the world. To be affiliated with this group of people was attractive to me. The combination of collections and staff being of very high quality, to tell you the truth, being in Boston was very attractive to me.

I was very conscious that there are problems here. The curatorial staff is concerned about what they see as the commercialization of the museum. This end of the museum is where all the authority lies and the curatorial offices are in the older, other side of the museum. That’s a perception that some curators have. I can change not just the perception but the reality. I enjoy curatorial opinion and I think of myself as a consensus manager. I love to hear what people think about things.

The curators are welcoming my management style which is to hear people out. To listen to what they think and mix it all together before I come up with my own opinion.

CG I’ve been covering the museum for a long time through ups and downs. The amenities have changed with an expanded spectrum including dining to retail. There’s popular programming from film to jazz concerts. The projection is more populist. But it’s rather like a Hollywood set. If you get behind the curtain it feels more hardball and that nothing has changed. There is the sense of departments as fiefdoms and entities onto themselves with little access for the public. The façade is more engaging but in reality, there has been not that much change.

AS What do you feel we should be doing?

CG There is little access to how things are done. For example, the acquisition of “Troubled Queen” by Jackson Pollock. It entailed deaccessioning two Renoirs and a Monet. That was done behind closed doors. When I tried to probe that process there was backlash from the institution and the director in particular. I learned that sources were instructed not to communicate with the media. Those who did were reprimanded. The issue was swapping apples for oranges. French impressionism for American modernism.

(By exchange “Troubled Queen,” valued at $1.6 million, was sold to the museum in 1984 by Stephen Hahn a New York dealer. The museum deaccessioned two works by Pierre Auguste Renoir “Young Girl Reading” (16 x 13”) and a pastel “A Woman with Black Hair” (23 x 18”) and “Autumn Scene” (24 x 29”) an 1884 painting by Claude Monet.)

I also investigated the relationship between billionaire Williams I. Koch and his foundation with the museum. My research revealed that the curator of European Paintings, John Walsh, was paid as a consultant to the collector. That seemed like an unusual relationship. It called to question the interaction of a non profit institution with the private sector and to what end? Were works collected with an understanding that they would come to the museum? In this instance that was less than clear.

There is secrecy and obstruction when trying to follow functions of the museum with responsibility to the general public.

AS That’s the way it is in every museum in America. It’s not unique to the MFA. The board of trustees is entrusted that’s what trustee means. They have a fiduciary responsibility for this museum. I don’t understand why, if their goal is public accessibility, a good mix of popular and scholarly, that they are abusing that power. If that’s the case, you have every right to probe and find out what’s going on.

They’re using their power, which is given to them by the charter of the institution, and the legal apparatus of the state. They’re using it to make a better museum with a more complete and encyclopedic collection by acquiring a Pollock. And I have no idea how that happened. Then I don’t see what the problem is.

What you are saying is that you don’t like the style with which you have been dealt with as a journalist.

CG That’s a part of it. The question arises as to whether the museum should make public the components of such an acquisition?

AS In New York City it’s mandatory.

CG If you make major deaccessions should you do that at auction?

AS On the other side of the coin should we publicly be discussing what we are acquiring?

CG Yes.

AS Before the fact?

CG No. In this case the issue was swapping 19th century French impressionism for American modernism? Are your trading apples for oranges? That’s drawing on a strength of the collection to make up for negligence in another area of collecting.

AS I feel very strongly that if you deaccession. That’s a word I don’t like. I prefer to say sell. If you sell from the collection there are several steps that have to be taken.

One. Find out where you got the work of art in the first place. If the donor is alive, the children or grandchildren. You go to them and inform them of your desire to sell. If they have any issues whatsoever the whole issue is dead. If people have left works of art to a museum, they have the expectation that the work will be there forever. If the donor is no longer alive you must go to the next living relative for permission. Even when the written will doesn’t require that. It’s a courtesy that must be followed. If you don’t get permission you forget the whole deal.

Two. With permission in hand you next go to your curatorial staff. I like to confer. I don’t like it to be one curator and myself. I want everyone to have input regarding the work that’s under consideration.

For example, we have so many Millets. (Jean-François Millet, 1814-1875) Why not sell one? You could argue that we don’t need so many. I would argue that we are a resource and scholars come here to study the artist. I’m against selling any Millets. I would take that as a very important consideration in a deaccessioning decision. It would diminish the importance of Boston as a Millet center. If the staff agrees then it goes to the trustees. They may know more about the family or background of the donor.

If there is one strong dissenting voice among the trustees, for me, that’s a veto. Once the object is sold, that’s it. That’s within the walls, however, I can’t have a thousand people writing and telling me what to do about deaccessions.

At that point you put the work in a public auction. That way there can be no doubt that you got full value for the object. That you did not waste the assets of the institution.

The other option to sell it is to approach several dealers. You can approach a dealer in London, Paris and a couple in New York. They do not know of each other. You ask if they are interested in buying or taking on consignment. You get back four bids. The competition between dealers is so great that they won’t confer.

You also ask the auction houses what they would estimate at. Then you make a decision about the best way to go. In terms of getting the greatest yield for the works of art.

There are safeguards against doing it wrong. You must then publish what you did in your annual report. In the same way that you brag about what you acquire. It should be public record. Particularly for scholars. Also, you keep a file alive in your institution indicating where and when you sold it. A scholar should always be able to track the object if possible.

When I was at Yale, I established there a very clear policy regarding the process for deaccessioning. It’s pretty much what I just described to you. You can be embarrassed when you sell. Particularly if you get too low a price. You can be embarrassed years later if a distant relative of the donor shows up and wants to see the object. It’s not there anymore and that can be humiliating. That’s why you have to proceed in the most cautious and conservative way.

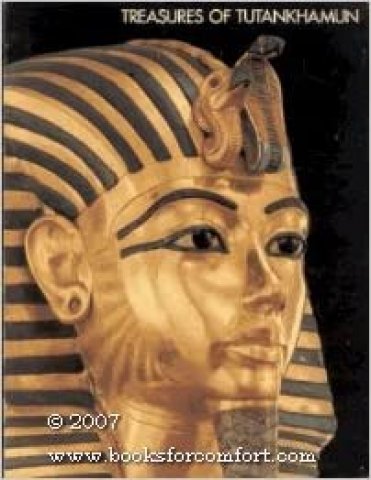

CG The King Tut exhibition was supposed to come to the MFA but didn’t. In many ways that was a turning point for the museum.

AS In a way it was.

CG There was the historically important relationship between Egypt and the museum’s Egyptian Department. If you recall, the museum was supposed to get the Treasures of Cairo exhibition but that got disrupted by the Israeli/ Arab war. The catalogue was produced but the show never traveled. There could not be assurances regarding potential acts of terrorism. That cancellation opened the door for a possible future project.

The MFA initiated negotiations for the Tut show which, as things turned out, went to the Met and National Gallery bypassing Boston. The reason given was lack of climate control. Losing out on a major exhibition, and the potential for others, was a game changer for Boston.

In competing for major traveling exhibitions what is the current status of the MFA?

AS It depends on what criteria you use for judging. If you base it on the permanent collection of the MFA. We are without peer in this country in Egyptian and classical art. That doesn’t mean we have the biggest collection but I would say that you’ve got to judge it department by department. For classical, object by object, there is no greater American collection. The National Gallery does not collect classical and we are far ahead of Chicago and Philadelphia. Because of the UNESCO convention it is now harder to buy classical art. I would take our collection over that of the Met based on the consistency of quality.

In Ancient Egyptian art there is no museum in this country that matches us though Brooklyn comes close. Then in European decorative arts without doubt the Met is ahead of us but we rank second in the nation. American decorative arts are spectacular and needs to be reinstalled someday soon, I hope. The collections of silver and furniture here are just fabulous. There we are on a par with the Met. There’s Winterthur and museums that specialize in decorative arts, but among encyclopedic museums, we are not beaten by anyone.

Where we fall down, as everyone knows, we failed to collect modernism and the 20th century. We’re paying the price now as we can never catch up to Philadelpia’s (Louise and Walter) Arensberg collection (of Marcel Duchamp and others). Our goal over the next decade can be to add ten to twenty wonderful early modern works. We can try to have a respectable showing. To play catchup would take hundreds of millions of dollars. You can get on Amtrak and got to Philadelphia to see Duchamp and Dali, Picasso and Braque.

Our prints collection is spectacular. It is a collection that, as a prints and drawings person, I have come back to over the years. It has been a place to recharge my batteries. The collection is so ravishing.

CG It has been described as the area of the museum that has the greatest potential for growth.

(There is a gallery named for collectors Lois B. and Michael K. Torf who focused on modern and contemporary prints.)

AS The print collection already has 500,000 sheets of paper. With Cliff Ackley there he’s done a great job.

(Although the MFA famously neglected to collect 20th century painting and sculpture the prints and drawings department was active in modernism. The Torf collection has expanded this with depth in contemporary prints and works on paper.)

In American painting, with our Homers and Washington Allstons, we are one of the best. The Met and National Gallery are also very strong in this area. You may argue our Thomas Cole vs. your Bierstadt but it’s a matter of apples and oranges. Boston has depth in Copley while Philadelphia is notable for Eakins. Chicago may have a tiny edge in French Impressionism.

With all these other strengths add to that our Asian collection which is the best in the world. Most Japanese scholars would acknowledge that the MFA’s collection is better than anything in Japan.

CG In areas of weakness how do you gain ground?

AS On average some twenty to thirty great works come on the market each year. The Getty has the deepest resources for acquisitions as well as the greatest need. They are having the fun of being in the market with its rough and tumble.

CG What lured you here?

AS After seventeen years in New Haven I got restless. So, I went to Minneapolis. (As director in 1985 for two years before the MFA.)

CG There were media reports that you were going to Chicago.

AS That never happened and I stayed at Yale from 1971-1985. With Chicago it worked out for the best. They got a wonderful director. I was the wrong person for that job. I went to Minneapolis in 1985. I loved that city and thought I would have a lot of fun there and stay for who knows how long. There I was when I got a call from the MFA search committee to be a consultant for them.

I met with them in January in that capacity. They asked me all kinds of questions about what I would do were I director. It was a couple of hours. They asked what kind of person they should hire and I answered to the best of my ability. When I got to the airport, I called my wife and said “I think they offered me the job but I’m not sure.” They called about three weeks later and said we would like to talk seriously with you about offering you the job.

I went back for another dialogue. It was a place I had always loved and felt that I could be useful. I felt badly about leaving Minneapolis so quickly. Things I wanted to accomplish there were just getting started.

CG It was a once in a lifetime opportunity. You have detailed the status of the museum and its collections. Where does it rank in terms of getting the major international traveling exhibitions?

AS In the top five.

CG There was a time when we weren’t getting those shows (Tut).

AS But that didn’t have to do with the reputation of the institution. What I have been told is that the museum didn’t have the appropriate special exhibition facilities with proper climate control. It wasn’t a lack of distinction for the institution but a facilities thing.

CG Wasn’t there also a kind of numbers game. To reach the maximum audience and geographic distribution the organizers of major traveling shows want one or two east coast museums, mid nation, and one or two west coast venues. Add to that the south with possibly Texas or Atlanta. Usually, that means the MFA and Met go head-to-head. Because of sponsorship and for diplomacy the National Gallery was another East Coast destination then perhaps Philadelphia or Baltimore.

AS Boston is the smallest of the three major East Coast destinations. In that game Philadelphia never seemed to be big. The question is how much attendance can you generate and handle. That is part of the economics of organizing these very expensive projects. You have to draw enough of an audience to pay for the cost of doing the show. A lot of that has to do with the size of the market.

In that respect Boston hasn’t been able to compete with New York. The percentage of tourists who visit the Met is far greater than tourists who visit the MFA.

CG How does the museum get its share of major traveling exhibitions?

AS I’m not so much interested in blockbusters but rather good, solid, balanced programming. To present something for every taste and a mixed diet of quality exhibitions as well as ones with the potential to bring in good attendance.

CG When John Walsh was head of European Paintings the museum had major shows of Chardin 1699-1779 (1979) and Renoir (1985). The Renoir show drew some 500,000 and produced a net of some $1million. The primary source of major exhibitions has been from the departments of paintings and prints and drawings.

(Renoir’s 97-painting exhibit drew record crowds in London and Paris. In Paris, Renoir drew crowds averaging 8,668 visitors per day. In London, it surpassed the attendance record of the Hayward Gallery. Boston was the only American venue of the exhibit. The prior MFA attendance record was for Pompeii, A.D. 79, with 432,000 visitors in 1978. Renoir topped 500,000. Under Shestack there was Monet in the ‘90s: The Series Paintings in 1990, curated by Paul Hayes Tucker, which drew capacity attendance. The exhibition was also seen at the Art Institute of Chicago and London’s Royal Academy of Arts. Tucker curated Monet in the 20th Century another blockbuster in 1998 that the MFA shared with The Royal Academy of Arts.)

AS We have shows scheduled through the classical and Egyptian departments. In the Gund Gallery in ’88 we have The Funerary Art of Ancient Egypt. We have a show of the figure in classical art in ’89. Classical Bronzes is also in ’89. So those departments will emerge. Little by little, until the turn of the century, everyone’s turn will come. Decorative arts and textiles are in line but we will soon have to make decisions about where next to turn our attention.

Cornelius’s (Vermeule acting director between Rathbone and Merrill Rueppel) term expired before we got to a project with the classical department. We have two classical shows now scheduled. Little by little those things will happen.

As I try to explain to everyone around here, in every museum paintings, prints and drawings are the major progenitors of exhibitions. That’s the way it is. Two dimensional objects are easy to work with. The works are relatively easy to install where an Egyptian show is hell on wheels. The objects are fragile and hard to move. Classical marbles are not to be moved at all if it can be helped. There are good reasons for these priorities. Prints and drawings are easy to transport.

So that’s the reason for showing a lot of photography but not the only reason. The logistics are so much simpler. But we are not ignoring the other departments.

CG Another factor is that some departments are rich while others are relatively poor. The Egyptian department resulted primarily through the archaeology of George Andrew Reisner who remained in the field for many years. Other than supporting the excavations, the museum did not purchase objects and few have come from private collections. Accordingly, the department is not well endowed.

By comparison the Asiatic and Classical departments are well endowed. Sitting at the round table of curators the contemporary department has the least resources. These are factors that determine the fiefdoms and power structures of the museum.

AS We’ve been fund raising for Asiatic renovations and have been very lucky to get Japanese support.

CG When the Asiatic department wants to build a new garden, they can get Japanese funding but the Egyptian department can’t rely on Cairo for support.

(During renovation the small, internal, traditional raked sand and boulders garden was relocated at grand scale to the exterior of the museum. The Tenshin-En Japanese Garden designed by Kinsaku Nakane opened in 1988.)

AS You can ask any museum director or college president and they will tell you that it is impossible to move forward with each department with equal energy simultaneously. You just can’t do that. You’ve got to establish priorities. The energies of your staff and resources available dictate that. You just have to do it one at a time. If we have to wait twenty years, I won’t be pleased but we till try to mitigate some of the problems. I promised the curators that I would not be a director who showed favoritism of one department over another. I weigh the positive and negative aspects of every proposal and give everyone a chance to have a fair hearing. To do it all at one time is physically and financially impossible.

(The management style that Shestack defined was to seek consensus through mediation. The executive authority of the MFA director was offset by the uneven power and influence of individual departments and curators. The success of the director was always a matter of balance. By mishandling the Raphael scandal board president, George Seybolt, forced the retirement of Perry T. Rathbone. Classical curator, Cornelius Vermeule, became acting director. There was a curatorial coup that resulted in the ouster of Merrill Rueppel. In the resultant regime change Asiatic curator, Jan Fontein, became acting director and then director. Shestack was hired to restore the more traditional balance of power between executive, curators and the board. Caught by an economic downturn his authority was weakened. Malcolm Rogers, who followed, soon initiated the policy of One Museum. He moved to consolidate and undermine the independence of departments. The summary removal of curators and staff was widely reported in the media as ‘The Friday Night Massacre.’ Security escorted individuals from the museum. Others left voluntarily.)

CG How the 26 departments play out is primarily an internal affair. To the outside community there is particular concern about the status of modern and contemporary art.

AS I haven’t been here long enough the address that. Generally speaking, I hope a new curator will be on board soon. We haven’t started interviewing. Because I knew this was an issue that would come up, I’ve been talking with friends from around the country in the contemporary art world. We have a dozen candidates.

(Kathy Halberich was director of MIT’s List Visual Arts Center (1976-1986). She was appointed as curator of contemporary art at the MFA. She left to head the Walker Art Center where she remained for 16 years. At the MFA her assistant was Trevor Fairbrother. From a field of eleven candidates he became curator of a three-person department which Shestack was active in supporting.)

CG What does the institution have to offer that individual?

AS There is likely to be support from a great number of collectors here in town. Particularly among those who have been following this issue will help with acquisitions and underwriting exhibitions. The director will be supportive and there are individuals who will a want to see that department flourish.

When I spoke with David Ross (ICA director) the other day he said that he welcomes what we are planning. There will be more lively communication and I think that’s wonderful. I’m conscious that there have been problems.

A question is finding adequate space. A lot of modern art is big. We have the Foster Gallery where we can install a nice medium sized show.

CG When Ken Moffett founded the department in 1971, he struggled to find support. How has that changed? Will there be an attempt to endow a chair and what kind of budget do you see for the program?

AS I can’t talk about that yet.

CG You can address the level of commitment.

AS I can talk about my commitment and the commitment I’m hearing from some of the people in town. But I can’t give you specifics. If we hire the right person everything will fall into place. I’m very optimistic about that. If we get someone in there full time it looks like the MFA is committed to contemporary art. People in the community will see that as a message to support that program. We are eager to see this situation resolved. But I’m worried about space. That’s my biggest concern. If in the next few years we acquire eight or ten enormous objects where do they go?

(The contemporary program was founded in 1971. Since 1992, the MFA has focused on art created since 1955 and today the collection contains more than 1500 works.)

CG To what extent will you use your expertise (prints and drawings)?

AS Probably not as all of my energy will be focused on solving the museum’s problems. I see myself as a facilitator and one who can bring messages back and forth between people who don’t agree with each other. I am trying to be a mediator and solve problems here.

(In 1993 he joined the National Gallery of Art as deputy director and chief curator until his retirement fifteen years later.)

CG To what extent will you be an ambassador attempting to bring major exhibitions to the MFA?

AS I have friends in the museum world in London and Paris, Germany and a few other places.

CG To what extent is a Philippe de Montebello a factor in landing major shows for the Met?

AS He is a very active ambassador for the Met. Carter Brown serves in that function for the National Gallery. I suppose to an extent I will be doing that. The curators here are very worldly people. They tend to do their own negotiations. Peter Sutton, for example, worked out all the details of his show with the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. I would certainly go to Amsterdam if I felt it would help. In my previous jobs I’ve gone to Russia and Israel. But I don’t see that as my primary function. Our curators are not afraid to speak for themselves.

But if somebody says we can get this show if someone goes and talk to the minister of culture in Romania or wherever, that’s my job and I go and do it. I may initiate some things but I’m not sure yet.

CG Do you miss scholarship?

AS No. I’ve written five books and now I have such a good job. When you take a museum job you don’t have large blocks of time for your own research. Unless you’re lucky as a curator to focus on exhibitions and writing catalogues. I’ve never had a job like that. Over the years I was able to crank out five exhibition catalogues. But this job rules out productive scholarship.

CG There has been a change in how museums are run. A Perry Rathbone, for example, had complete authority. Later there was a shift to the director as presiding over aesthetic decisions, acquisitions and exhibitions. Now there is the more usual approach of major museums to divide that with a director and business manager.

AS When Rathbone stepped down it took two people to replace him. When I step down I recommend that the museum have a coequal president. I prefer the situation I inherited where I’m CEO and there is a deputy director who deals with administrative problems. I don’t worry about purchasing paper clips. A museum director shouldn’t have to focus on that. The former directors didn’t have all the problems of the new museums with expanded marketing, retail and food services.

If there is a situation where the division of responsibilities overlap, I would have the final decision. We have to do what balances the books at the end of the year. But we are a long way from having sold our souls to make that happen.