Francesco Clemente's Encampment at Mass MoCA

With Jim Shaw to January, 2016

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 13, 2015

Writing about “Superman Body Parts’’ from “Jim Shaw: Entertaining Doubts” at Mass MoCA though January 2016, Sebastian Smee in the Boston Globe stated that “.” The exhibition, organized by Mass MoCA’s Denise Markonish, might prove to be the show of the summer.”

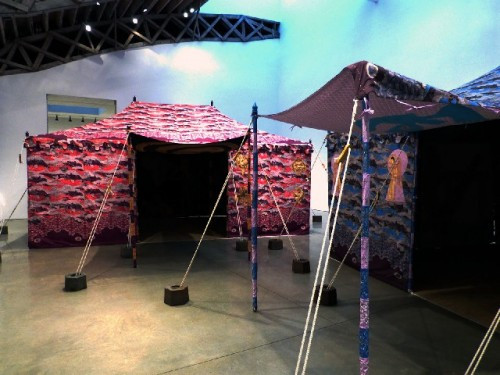

That bold statement written several months ago predated the opening of The Clark Art Institute’s "VanGogh and Nature” which opens with a gala this weekend. Last night Mass MoCA unveiled Francesco Clemente’s “Encampment” a multi-part 30,000 square foot installation in the museum’s vast Building Five gallery. Like the large Shaw installation with theatrical-like painted backdrops and accompanying galleries of Surperman inspired paintings and drawings these shows will both be on view until the New Year.

As a droll observer of all things Mass MoCA commented during the vernissage there is an ironic synergy between the loosey goosey, cartoonish, ersatz vaudevillian, campy images of Shaw and Clemente. One wonders if the pairing and juxtaposition in contingent spaces in the museum was deliberate or serendipitous.

Were the dada prankster Marcel Duchamp to visit the museum he would be likely to find the works on view “too retinal.” Duchamp was a skilled painter. His “Nude Descending a Staircase” in a cubist/ futurist style caused a sensation when shown in the seminal Armory Show which introduced the avant-garde to America on the eve of WWI.

His signature painting was mocked by a journalist as “An explosion in a shingle factory.”

Not long after Duchamp denounced hand crafted art while inventing the Found Object, Readymade and Assisted Readymade. The artist, whose influence has proven to be more pervasive and enduring than that of Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian, Miro or Malevich in a singularly passive aggressive manner also pioneered conceptualism and performance art.

In the debates that have prevailed ever since Duchamp either widened the scope of art or utterly destroyed it. These dichotomies may escape the general public but are pursued with passion by those who take them seriously.

Recently, for example, I posted poems about John Cage, Philip Glass and Ornette Coleman who passed away this week. I had opportunities to meet with, interview and photograph these exemplars of the contemporary avant-garde. It would be absurd to claim that I understand their work. They each demand intensive research and daunting case studies. But I appreciate them as creators and find their mandates fascinating and inspiring.

But the Cage/ Glass poems evoked a heated exchange with a composer of music in the classical tradition. He dismissed Cage as a “Charlatan” and described the serial music of Glass as “Wallpaper.” Efforts to expand the discussion to jazz and improvisation were unproductive. The thread of discourse was terminated rather than resolved.

During the post WWII era and the emergence of abstract expressionism as a globally dominant movement of art aesthetic argument gravitated to jingoism and the polemical. The formalists claimed the aesthetic high ground that only abstraction and non objective art represented the purest and most elevated work. There was a total rejection of the strident social realism and literary, illustrative regionalism that was sacrificed on the altar of Parnassus for the phoenix like rebirth of the Triumph of American Art.

Starting with the Ancient Greeks there has always been a dichotomy between the purity of the Apollonian and the orgiastic expressionism and humanism of the Dionysian.

“Masscult and Midcult,” Dwight Macdonald’s famous essay in cultural taxonomy, distinguished three levels in modern culture. In 1939 Clement Greenberg published the influential essay “Avant-garde and Kitsch.”

By Macdonald’s standard the Clemente/ Shaw exhibitions are likely Middlebow and Kitsch by Greenbergian paradigms.

Given the prevailing eclecticism Macdonald's categories might be upgraded to Good, Bad and Indifferent.

With the general demise of the influence of critical thinking the evaluation of works of art is reflected in prices set by dealers and auction houses. The quality of the work is secondary to what it sells for. The market rules and for artists living well is the best revenge.

Through several generations abstraction eventually came to a dead end with the dissolution of Color Field painting into ever more discharged tributaries. The gushing great white water of the mainstream of Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko and Reinhardt was ever more diluted.

A recent revisionist treatment of founding color field painter, Helen Frankenthaler, and artists influenced by her was presented at the Rose Art Museum. It was given serious critical attention by Roberta Smith in the New York Times. Perhaps yet again it is time for emerging artists to water down their acrylics.

The widely discussed Return to the Figure that was to follow Abstract Expressionism was diverted into the neo realism of Pop art and its ironic exploration of post war American prosperity and consumerism.

As I tried to argue with my composer friend it is possible to find inspiration in the avant-garde of Cage, Glass and Coleman as well as all work that is clear, compelling and insightful on its own terms. It is possible to admire the work of Pollock and Warhol, Stravinsky, Miles Davis, John Cage, Benny Goodman and Dolly Parton.

The challenge is to treat the work of art on its own terms. Abandoning the neo Platonic a chair may have many forms and functions of equal value. Appreciating one genre of art does not negate all others. A compelling experience of art may be heads or tails or heads and tails.

We are now so far beyond the polytheism of post modernism that nobody is finger pointing at the reactionary, representational aspects of Clemente and Shaw that were so thoroughly renounced by the formalist critics whose influence subsided. There was weak mainstream critical resistance during the emergence of the neo expressionists that included Clemente as well as Julian Schnabel who makes movies and the once more widely admired David Salle. With the tents Clemente has reinvented himself and is again swimming in the critical mainstream,

As the stripper informs us in the musical Gypsy “Kid you gottah get a gimmick if you wannah get ahead.”

At Mass MoCA that equates to the Tent City of Clemente and a séance with Superman evoked by Shaw.

Actually, what’s not to like? In a formalist’s worst nightmare these installations are fun, fun, fun and awesomely accessible.

Unlike an exhibition of conceptualism or abstraction it doesn’t take a critic to explain and decode the work. Everyone knows that criticism is obsolete. Seen another way everyone with an I phone and a Facebook page is a critic. In our millennial culture anyone with an opinion is a critic.

In that regard your opinion of the work is just as valid as mine. Perhaps more so as it is reflects your ego and prejudices.

De gustibus non est disputandum.

Which is to say that I do and don’t take this work seriously. It is problematic on many levels particularly as it plays into Guy Debord’s arguments about Spectacle as a post modernist paradigm. The French theorist, Debord, is quoted in the museum’s pr which is pretty far out if you think of it. Not one in a thousand readers will have a clue about Debord and the Situationist International which was pretty groovy back in the day.

MoCA states that “Quoting Guy Debord’s seminal text, The Society of the Spectacle, the flag that hangs from the top of Hunger is embroidered with the words ‘the spectator feels at home nowhere because the spectacle is everywhere.’ ”

OMG.

Back in December I encountered two of the tents of Clemente at the Mary Boone Gallery in Chelsea. The works were surprising and challenging. It was certainly a bold departure for an artist that I thought I knew fairly well.

There was an inherent awkwardness and disconnect. The conceopt of a tent implied a range of associations. It is grounded in the notion of a temporary outdoor structure. It can be a place of shelter for campers, an environment for a circus or wedding, a portable home for nomadic people. With their painted interiors Clemente has been asked about them as sacred places, temporary temples or even primordial caves.

His very decorative and fragile tents are not intended to be durable and installed outside.

At Boone and MoCA the tents are tethered to large weighty blocks. My initial reaction was how this would equate to being shown in a museum or private collection. Their installation demands a lot of space.

The vast space of MoCA’s Building Five is either half empty or half full. In this case the tents are installed in the space in a manner that has no synergy with its ambiance. They are preexisting works that are installed here. This is not another example of an installation specifically designed and fabricated for the space. This exhibition evokes a traveling tent show like the circus or carnival passing through town.

Entering the gallery there is the long “approach” until we encounter the cluster of tents. There is a haphazard design as we explore them.

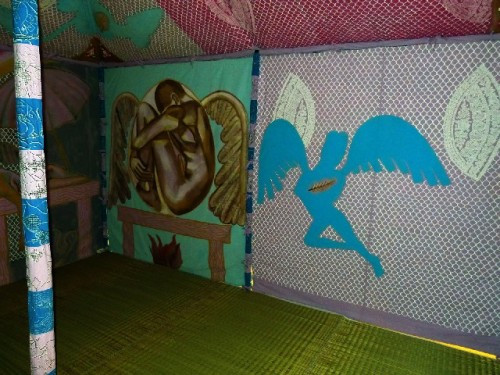

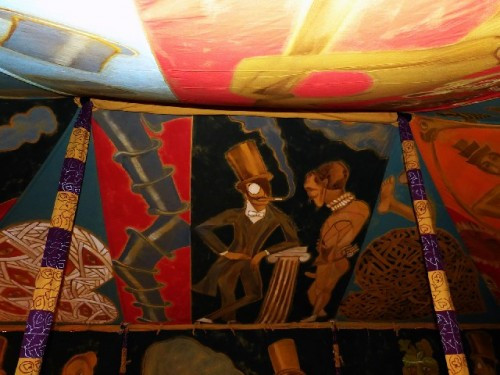

The MoCA press release states that “ Created over the course of three years from 2012 through 2014, in collaboration with a community of artisans in Rajasthan, India, the large 2-pole structures (each measuring some 10’ x 18’ x 12’ high) transform MASS MoCA’s signature Building 5 gallery into a kind of tent village, inhabited by painted human figures both supine and in motion, and emblematic symbols and signs both obvious and arcane. Secured in place by ropes and special cast-iron weights, the exteriors of the large bamboo and fabric tents are richly decorated with hand-printed woodblock designs, carved after drawings by Clemente. The patterns recall the camouflaging on the uniforms and gear of the Indian Army in Rajasthan — the visual resonance of which is heightened by the region’s complex social, political, and military relationship with Pakistan, whose border it shares. Closer inspection of the camouflage patterns reveals esoteric texts, embedded icons, human silhouettes, and other subtle signs, all intricately outlined with hand-embroidered gold-colored thread. Inside the tents, walls, ceilings, and entryways are awash in richly toned jewel-like paintings. Depictions of love and carnal desire are juxtaposed with trompe l’oeil paintings of framed portraits of Clemente, for example, in which the artist’s arm and hand reach through the frame, grasping towards viewers. Implicating our very presence in the museum, Clemente draws visual parallels between erotic voyeurism and the spectatorial enjoyment of art…”

At Boone Gallery I explored and photographed the imagery in the tents. In a brief review I wrote “Thematically there was an emphasis on decadence and class in a circus like context. There were a number of cavorting renderings of a billionaire in tuxedo and tall silk hat with a signifying monocle. He appears to be repressing servants or sex slaves stripped and crawling like animals on leashes.”

The images are painted in an aqueous, ersatz naïve, outsider manner. This has been a constant in his work since it emerged in the 1980s. There is always a casual, intuitive approach. Critics have often commented on a connection to classical Indian miniature paintings. The Italian born artist divides time between New York and India.

There is a connection to the indigenous folk art tradition of vaudeville and circus billboards. In contemporary art history these works have been conflated into the main stream of high art and critical thinking. Clemente has been renowned for exploring the thin edge between naïve and high art. What tips the work into the latter category is its inventive installation and conceptualism.

Of course none of this theoretical discussion will mean much to the museum’s visitors. The shows are likely to have enthusiastic audiences. This includes all the rock fans who explore the galleries during Wilco’s Solid Sound Festival. Or the VanGogh folks who wander over from The Clark. Also don't miss the massive Warhol show at the Williams College Museum of Art.

The combined forces of The Clark, WCMA and Mass MoCA assure a blockbuster season for cultural tourism in Northern Berkshire County. What's not to like about that?