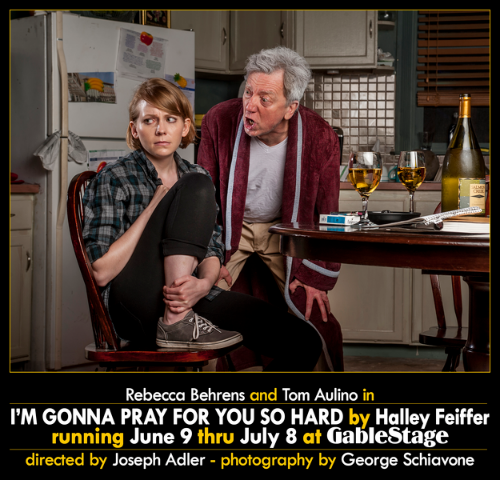

I'm Gonna Pray For You So Hard

Play by Halley Feiffer in South Florida

By: Aaron Krause - Jun 25, 2018

Our desire for affirmation that others value us is sometimes as strong as our hydration needs on a sweltering day.

Playwright Halley Feiffer illustrates this with penetrating insight in I’m Gonna Pray For You So Hard.

But praying may not be enough when others reject us. Such rejection can affect us so adversely, that we end up without power to stop destroying ourselves.

Plenty of self-destruction occurs in Feiffer’s dark, daring, absurd and comic play. GableStage, near Miami, is presenting it in a mostly riveting production through July 8.

Indeed, the characters feverishly snort cocaine. They also smoke and gulp liquor as though it were much-needed water.

Sure, there’s poison aplenty in David and Ella’s present-day Upper West Side Manhattan apartment (designed spaciously, elegantly and with detail by Lyle Baskin). However, an entirely different type of poison sets into motion this father and daughter’s self-mutilating behavior. This other poison originated from the pens of critics.

With this in mind, welcome to the bipolar world of veteran actor David and his daughter, young, green performer Ella. To be sure, there’s nothing complicated plot-wise. Mostly, over the course of a long evening, dad and daughter drink, snort, smoke and decide whether to read reviews of her performance as Masha in Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull.

As a matter of fact, Feiffer’s play sometimes has a Chekhovian feel. Ella sinks into despair and hopelessness while facing her formidable dad. He changes his demeanor with the frequency of a shifty politician.

Of course, one can’t blame this insecure young woman for her behavior. After all, she adores her father.

And why not? He soothes her with the kind of love you might expect a parent to lavish on his adorable toddler. David also exudes charm and likability. He regales Ella with tales about his troubled past, but also his indomitability and brush with Broadway fame.

Needless to say, a transfixed Ella, communicating girlish excitement, cannot take her eyes off her father as he dramatically relates his exciting past.

But just as light-heartedness pervades the room, darkness invades. David admonishes and belittles Ella for allegedly failing to audition for Nina in The Seagull. This part is meatier than Masha, in dad’s mind. Furthermore, it went to a less-talented but better-looking actress.

The lasting effect from dad’s severe criticism, and the critics’ harsh words, seems never-ending.

Suddenly, Feiffer’s ferocious, biting play, with all its booze and drugs, feels like Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night or Tracy Letts’ August: Osage County.

To further unnerve us, while David speaks casually and playfully at times, there’s a slight undercurrent of menace in his voice. All this, while Ella is sobbing uncontrollably or begging for dad’s approval.

“Nothing to be done,” he says casually and mater-of-factly. He’s referring to the famous line from Samuel Beckett’s existential, absurdist classic Waiting for Godot.

Speaking of renowned works, Feiffer deftly weaves in lines from classics to fit within the context of her play.

“So how come you’re not a star?” Davis asks Ella rhetorically. The answer is “as random and meaningless as the universe.”

Meanwhile, Feiffer expresses one of Ella’s other desires through the West Side Story song, “Somewhere.”

Its presence in Feiffer’s play isn’t by accident.

Indeed, who doesn’t need to feel there’s a place for them in their family?

The one Feiffer depicts in her play might be dysfunctional.

Still, this is a family. And even in their dysfunction, such clans can be among the most loving.

But this isn’t your average dysfunctional family play. In fact, it’s hard to neatly categorize. Feiffer’s piece is part love letter to the theater and part criticism of its tendency to play it “safe,” staging easy to digest plays at the expense of meaty works. Feiffer’s dramady is also part absurdist, part tragic and even cruel, but always entertaining.

This much is certain: Feiffer isn’t interested in making you feel good or comfortable. For instance, there's no happy, neat ending or denouement. There’s a sentimental scene toward the end featuring a weakened, ailing David who’s just suffered a stroke. Slowly, he walks toward Ella, now a confident artist at a downtown black box theater. To the tune of "Somewhere," dad sings apologetically for basically having been a rotten father. We sense forgiveness is forthcoming.

But Ella’s almost unthinkable reaction should leave you aghast. Apparently, sometimes there isn’t a place for a shred of kindness or human decency.

Still, if Feiffer is out to depict with unflinching honesty how cruel people can be, the author also writes with insight and sensitivity.

GableStage’s producing artistic director, Joseph Adler, has staged this play with equal emphasis on its light and dark aspects.

Sure, there are moments that could use improvement. For instance, when David tells his daughter about his childhood, one of the things he mentions is how cheap it was to secure a front row seat to a Broadway show. Ella (Rebecca Behrens) could register more surprise.

But Behrens mostly shines in this role.

The first act is basically one long monologue by David (a fine Tom Aulino). While Behrens speaks mostly short sentences during the monologue, her telling facial and body postures are appropriate. They include wide, excited, eyes, sitting still and attentively, looking up in admiration to her father, looking lost and forlorn and pleading non-verbally with dad.

During the second act, Ella seems like a different person. Gone is the nervous, giddy, girlish Ella. Behrens has replaced her with a confident, commanding, assured artist.

Meanwhile, Aulino offers a tour-de-force performance.

One gets the sense the actor is being careful not to immediately turn David into a ferocious man. If he did, it would make more sense for Behrens to fear David, rather than love him and desire love back.

Perhaps with this in mind, Aulino, at first, exudes some charm and gives us a curmudgeonly kind of David, complete with a scratchy type voice. But make no mistake: The actor slowly, but surely, builds intensity, until David is a man with whom you don’t want to mess. He’s an impulsive, explosive and even more bitterly sarcastic man. Moreover, he's thoroughly ashamed at his daughter, whom he believes has embarrassed him, his profession and the American theater.

In the second act, Aulino acts and appears a bit too sturdy. We need to see more fragility and vulnerability as he approaches his daughter. It would enhance the tragic element of the play.

With all the drug use, smoking (the actors use herbal cigarettes) and chugging liquor with abandon, it’s easy to leave the theater with this thought: I’m, indeed, gonna pray for these people so hard.

In today’s world, our society could surely use the prayers.