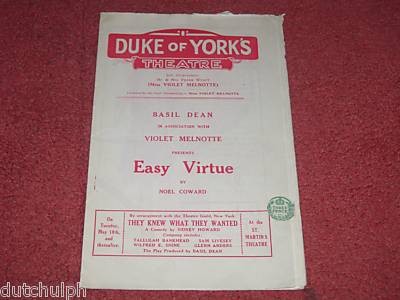

Noel Coward's Easy Virtue

Stephen Elliot's Adaption of 1925 Play

By: Susan Hall - Jun 27, 2009

"Easy Virtue," Stephan Elliot's adaptation of a 1925 Noel Coward play and now a delicious movie, opened to limited release in the US on May 22.

The play, considered second tier Coward, was well received when it premiered in Newark, New Jersey and later during a Broadway run and transfer to the West End. Young auteur Alfred Hitchcock made a silent film based on the play. Why would Hitchcock have been attracted when Coward is first and foremost a wordsmith and sound was not available for the 1927 production?

Hitchcock starts his film with a screen title that reads, "Virtue is its own reward, but easy virtue is society's reward for a slandered reputation." Webster says: A loose woman. Coward: A charming person. Elliot indicates: What seems to be easy virtue is only a reaction to very difficult moral decisions whose outcome is not always clear and a reward to the individuals who act with courage.

Coward was obsessed with charm and tries to show his protagonist Larita's charm as an act of courage. She is a figure of style and taste. Coward's description of her entrance at the end of Act I: "She is tall,exquisitely made up and very beautiful--above everything she is perfectly calm. Her clothes, because of their simplicity, are obviously violently expensive: she wears a perfect rope of pearls and a small close traveling hat."

Sex is a subject -- in Coward blanketed in language, in Hitchcock shrouded with mystery, and if you cast Jessica Biel as Larita as Elliot has, front, forward and fun!

In all three takes, Larita is a woman of an uncertain past who meets a young Brit on the Riviera. In Hitchcock, she signs into a hotel under an assumed name, wishing to shed her notoriety after she has been judged guilty of misconduct toward her first husband. She is ready for a new life when the young John Whittington hits her in the eye with a tennis ball. This young member of the fading English landed gentry is immediately smitten and proposes marriage.

Larita is frank:" Don't you want to know anything about me?"

He shrugs the question off: "I love you. That is enough." They kiss in a horse drawn carriage overlooking the Mediterranean, the horses kiss, and the traffic jammed behind them is appeased by the romantic display. Not your usual Hitchcock cool.

Returning with Whittington to the family estate in England, a rather plain affair in Hitchcock, his family instantly hates her. Her mother-in-law keeps saying she remembers Larita's face. When an old newspaper is held up to the camera, we know Larita will not end her life as mistress of the manse. Tabloid headlines detail a passionate romance with an artist who her husband had hired to paint her portrait. The crucial question -- was the maid always in the studio when Larita undressed -- did not resolve in Larita's favor. The Hitchcock back story is a prescient indictment of yellow journalism. Elliot saves his back story for a zinger at his film's end.

Under the cover of manners, Larita lobs insights at her new in-laws. "How-do-you-do seems so hopelessly inadequate, doesn't it, at a moment like this, but perhaps it's good to use it as a refuge from our real feelings."

Larita's charm comes from a combination of self-awareness and sincerity which make her all the more appealing to every one but her husband's family. Larita fends off all the bile with wit: "I've never had an affair with a man I wasn't fond of."

In the play and both movies, her mother-in-law dredges up an old scandal to hound her with.

Mrs. Whittaker: And how have you lived since this -- this scandal?

Larita: Extremely well.

Mrs. Whittaker: Your flippancy is unpardonable.

Larita: So is your questionÂ….

Mrs. Whittington: In our world, we do not understand easy virtue.

Larita: In your world, you understand nothing.

The scandal however has different twists in the different Easy Virtues. In Coward, it is the fact of the first marriage; in Hitchcock,an innocent woman is wronged to satisfy our prurience; Elliot deepens the whole matter to look at the seismic changes wreaked by the Great War. This resonates in our own time.

There's never a question about Larita's appeal: Her grand entrance to a party at which she's not welcome captures the Coward stage directions: "Her dress is dead white and cut extremely low...her face is as white as her dress and her lips vivid scarlet. She is carrying a tremendous scarlet ostrich-fan. There is a distinct gasp from everybody." Hitchcock precedes this with a scene in which Larita's maid makes deep inroads into her gown with scissors, revealing ever more back and front. As Larita descends the stairs, every head turns. Her sister-in-law drops a cup of claret. Every man registers her magnetism.

Hitchcock brackets the film with two divorce trials - in the second, her weak husband can't stand up to either his mother or the first scandal. Larita says at its conclusion, standing on the court house steps, addressing the reporters and photographers packed around her (like Richard Nixon exiting from a California gubernatorial race he lost in 1962), "Shoot. There's nothing left to kill."

So why did Stephan Elliot, whose "Priscilla of the Desert" will soon be mounted as a musical, elect to develop this piece with its own history?

He guessed what a grown up Coward would have made of the same situation (Coward was just twenty-five when he wrote the play). And perhaps Coward would have gone in the direction Elliot has chosen, since he is the quintessential English portraitist of the period between the First and Second World Wars. The period immediately prior to and after the First World War is the last monumental shift before our current tsunamis, which will land us we don't know where.

Larita's first marriage in Elliot's version ends in a conscious act of conscience. (This information is withheld until the very end of the film.) Colonel Whittington, father of the groom, a minor character in the Coward play and the Hitchcock film, is enlarged and played brilliantly by Colin Firth. Having led every one of the troops from his small village to death in the Great War, he is a tortured man. By comparison, every other character except Larita is silly. Acts of conscience and their aftermaths are examined in the film, giving meaning to their moment and ours.

My guess is that when we come out of the current mess, many of us will live in a new conscious place, driving battery operated cars, buying free trade market bags, wearing Eileen Fisher clothing and who knows what else. In some ways, the president we elected in 2008 is the beginning of such vibrantly conscious choices. These words conscience and conscious, both at the center of the Elliot film, are closely related, derived from the Latin -- To be knowing, aware. Knowledge within oneself, a moral sense.

Don't be misled by sober thoughts. The current film is a romp. Larita's solution to her mother-in-law's order that she ride to the hounds, which offends her own feelings for the fox, is unique. The funny murder she commits on screen may offend animal rights activists, but is clearly accidental. Elliot reports that the two female leads -- Kristin Scott Thomas, dowdy and fearful, and the luscious Jessica Biel (who once said she did not know why she didn't get to play comedy just because she was physically fit: translate, hot) -- were extremely jealous of each other on the set. Or perhaps more correctly, Thomas could not stand Biel's voluptuous glamour. This real life jealousy seeps compellingly onto the screen. Biel delivers one witty Coward line after another and her talent certainly doesn't surprise after her star turn in "The Illusionist." Turns out she can also sing having appeared in "Annie" and "The Music Man" at age nine.

If you can't find the film at a local theatre it will soon be available on Netflix and at your local video store. It's enormously entertaining and provocative.