Was Malcolm Rogers the MFA's Greatest Director

By Far Its Most Controvesial

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 01, 2020

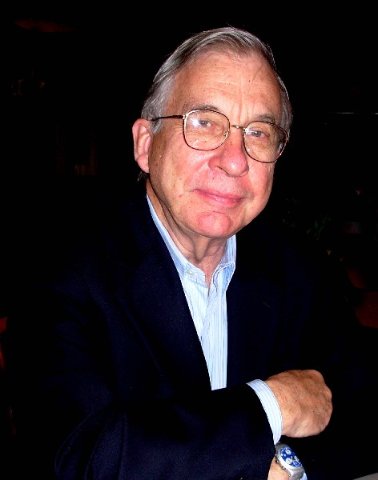

Malcolm A. Rogers, CBE (born October 3, 1948) served as the Ann and Graham Gund Director the Museum of Fine Arts from 1994 through 2015. Rogers was Deputy Director of London’s National Portrait Gallery before seeking a position in Boston.

As director Rogers made sweeping changes that were controversial. About which the jury is mixed. The opinion of the late critic David Bonetti, in a 2014 piece for Berkshire Fine Arts, however, was unequivocal.

“To begin with, you have to admit that Malcolm - as everyone calls him, whether he likes it or not - was the MFA's greatest director since the end of World War II. (since I don't know the history before that that well, I can't say whether he was the greatest director in its history, but I suspect that he might well be a contender.)”

During an economic downturn the museum had fallen on hard times under prior director, Alan Shestack, who served from 1987 to1993. Rogers was given a broad mandate to kick-start what had become a moribund institution.

In June 1991, under Shestack, the board ordered the administration to trim $1.7 million off a projected $4.7 million deficit. Forty-two positions were affected, and 21 people were laid off. The MFA had borrowed an estimated $6 million to $10 million from its endowment, which had decreased to $145 million. As a part of cost cutting the grand Huntington Avenue entrance was closed. Rogers soon made staff cuts that shaved $3.4 million off the museum’s $4.5 million deficit. More cuts and shakeups would follow.

We met for the interviews that follow. There were others as well as lunch. For the first he had been on the job for just seven weeks. The second occurred September, 2011, during the opening of the Linde Wing of Contemporary Art.

New to the job there were signifiers of policy positions that would erupt under the mantra of One Museum. Through growth of the endowment, brick and mortar expansion, property acquisition and collections growth, arguably, he left the museum in better shape than he found it.

When Rogers arrived in 1994, the budget was about $77 million; today, it is more than $101 million. The number of visitors was 864,179 in 1994, and 1,227,163 in fiscal year 2015. The endowment grew from $180.6 million to $623.7 million today. The museum’s debt, however, grew from $35 million; to $189 million at its peak, through construction and the 2007 acquisition of the adjacent, former Forsyth Institute. The current administration of Matthew Teitelbaum inherited a debt of $140 million.

While there were undeniable efforts toward fiscal balance and physical expansion, Rogers accomplished this while ravishing the independence of the museum’s world-renowned curators and their departments. When the dust settled it was said that he micro-managed their domain. His mantra of One Museum left little doubt as to who was in charge.

The special exhibitions on his watch were often populist. These ranged from the commercial photographer, Herb Ritts, to the vintage cars of Ralph Lauren, Dangerous Curves: The Art of the Guitar, An Adventure with Wallace and Gromit and the mediocre collection of billionaire William I. Koch. The installation included empty bottles from Koch’s wine cellar, Native American Antiques Roadshow items and two of his America’s Cup yachts parked in front of the Huntington Avenue entrance. The Rogers program also included Goya and the prints of Katsushika Hokusai.

Garish works by the populist Takashi Murakami were installed in galleries of the world class Asiatic collection. As a renowned gallerist told me, encountering them in that context “Made me want to puke.”

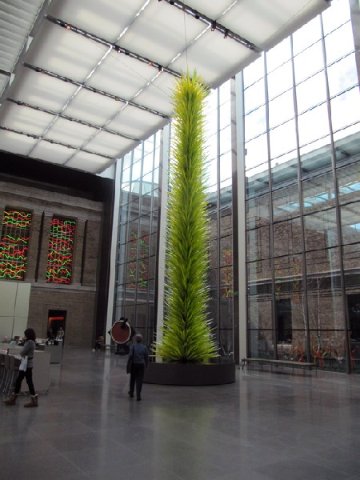

The glitzy glass sculptures Chihuly: Through the Looking Glass drew crowds in 2011. Money was raised to purchase an enormous, Christmas tree-like, tchotchke. It remains in the enormous atrium, dining, visitor’s center of the American Wing designed by Lord Norman Foster. During holiday season it is a space prized for corporate receptions.

The Chihuly exhibition seemed to bring Vegas taste to Boston. It is no surprise then that the museum’s priceless works by Claude Monet were rented to the Bellagio for a million dollars. In addition to a contractual agreement with a museum in Nagoya, Japan the museum’s treasures were often on the road to earn their keep. These loans were for commercial gain rather than the quid-quo-pro of scholarly museum exhibitions.

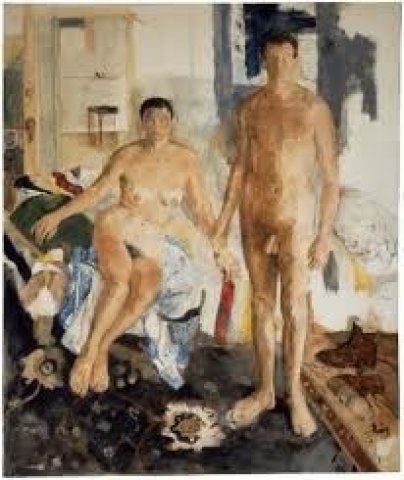

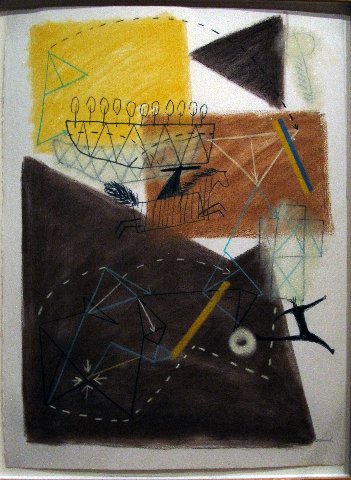

The MFA presented 375 exhibits during Rogers’s tenure, from ancient Chinese art to David Hockney, Ellsworth Kelly and Impressionist masterpieces. The museum acquired some 67,000 works of art, including a $20 million-plus painting by Edgar Degas, “Duchessa di Montejasi with Her Daughters, Elena and Camilla.” In modern and contemporary art, the late doctors, Melvin Blank and Frank Purnell, donated 60 works by surrealists and an early nude by pop artist Larry Rivers.

The museum has a long and ambivalent track record on issues of diversity and inclusion. In 1969, Edmund Barry Gaither became director of the National Center of Afro American Artists. It was allied with the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts. In 1970, Gaither curated for the MFA Afro American Artists: New York and Boston. As Special Consultant he went on to curate seven more exhibitions for the museum. On his watch works were acquired for the permanent collection.

John Axelrod, the philanthropist, credits Rogers with initiating an internal diversity report and action plan in 2002. In 2011, Axelrod sold 67 works by African-American artists to the museum for $5 to $10 million. He also helped fund “Common Wealth: Art by African Americans in the Museum of Fine Arts,” a comprehensive catalog edited by curator Lowery Stokes Sims. It documents some hundred acquisitions since 1970. The museum is committed to expand on this foundation. Vintage acquisitions included renowned Boston artist, Alan Rohan Crite, and outsider artist Horace Pippin.

We spoke in 1994.

Charles Giuliano Can we talk about Nagoya (Museum in Japan)?

Malcolm Rogers We are getting close to a contract. I have been here just seven weeks now and I wasn’t involved in the negotiations.

CG Your predecessor, Alan Shestack, expressed that this would help to address deficit issues. It is thought of as a key piece of the puzzle of resolving a deficit.

MR It’s an important part of the puzzle as well as a part of our outreach.

CG It has been projected to bring in at least $1 million annually.

MR I don’t have an exact figure as the process is still in negotiation. We have been running a deficit this past year approximately $4.5 million with an operating budget of $60 million.

There are certain things you have to know about the deficit. Some 5% of the spending capital of the endowment is set by the trustees so that you can build up endowment. It is set aside and invested as a reserve. In case there is a special project or an emergency. To be perfectly honest our structural deficit is about $2 million a year.

CG In recent years there has been a lot spent on construction. What is the debt service on those loans?

MR About $2 million a year.

CG In the 1980s there was extensive museum expansion. There was a decision to climate control special exhibition galleries to accommodate major traveling exhibitions and to provide amenities as well as refreshed collection galleries. You have inherited the responsibility of paying for those brick and mortar improvements. The MFA has seemed out of the loop. Boston lost out on the Rembrandt show that Peter Sutton initiated for the museum.

MR In hindsight we realize it would have been better to be building and fund raising at the same time. Looking on the positive side because of the building that was put up we have doubled attendance.

CG Jan Fontein is remembered for expanding the museum while Alan Shestack was increasingly burdened with managing the museum through a declining economy. You come in with that over your head which is a daunting undertaking. Knowing that why did you want this job?

MR When I was considering coming here there were some 20 major museum positions to be filled. There I was in London thinking America might be an interesting place to work. I looked at those twenty positions and one stood out. It was literally the best job which I started to chase. I knew the MFA very well as one of the greatest museums in the world. In one of the finest cities in the world.

It was also an impossible job to do. I liked the idea that it was a difficult job in a great, great place.

CG What’s the difference between impossible and difficult?

MR (laughing) I don’t think there are any impossibilities. The impossibility is thinking it’s impossible. In my very first message here, and I tend to say and write what I believe, it all broke down into challenges. There are committed, able people here who love this museum when you enable and empower them to do their job. I was convinced that we can turn it around with the support of the trustees, with the support of our staff and motivating it. Clearly, we have to think long and hard about how to use our resources.

No doubt you read in this morning’s Globe about Mr. Rogers. I wouldn’t put it the way that Christine (Temin) did. Have we got the balance right between permanent and temporary exhibitions? The permanent collections are important but are they more important? It’s difficult to say what’s the right balance? My feeling is that we should be doing a certain number of exhibitions a year but we should also be improving a certain number of permanent displays each year. That you would have budgets for education plans that fit into the museum’s mission. Exhibitions, temporary and permanent, should be planned well ahead and we should know why we want to do them. We can’t just exist. We have to be a priority for visitors.

CG The programming has been a bit dull. Because of the deficit and funding there seems to have been too many in-house exhibitions with things dragged up from the basement.

MR (with emphasis) Can I assure you that I do not intend to drag up shows from the basement. Can I also say to you sometimes we try to use a bit more imagination? When we did our recent Egyptian mask exhibition, many of the objects came out of storage and are international treasures. They have been put into a gallery that is used for education. We hope it will be a major public attraction and that is not an attempt to palm them off as a temporary exhibition. It’s quite different.

(Long pause). How do I put it? What it comes down to is planning well ahead and knowing what we want to do. What will be as effective as possible. I sense what you are thinking about but a retread can be so much more than that. Ah, what’s the word I want. (pause) The opportunity to have an exhibition which just happens to be around, as a long-term planner, we have to explore the bounds between temporary and long-term exhibitions. I’m not saying to do permanent displays because they are cheap to do. Often, they proved to be more expensive. But our permanent collection is incredible and it’s what is so special about this museum.

I’m not in the business of doing things to save money. Whatever we do must be professional to the highest standards.

CG In the past few years we have had a diet of in house shows.

MR What do you mean by diet? I’m not so sure of that.

CG The generic, thematic impressionism show a couple of summers ago played like the basement’s greatest hits with some highlights and a lot of filler. It was formulaic in finding a way to recycle crowd pleasing impressionism. It did not make a strong scholarly or aesthetic point. Actually, it didn’t make much of an impression and I don’t remember much about it.

MR Could you check the dates about that. The show that’s up presently I did not choose personally. I would have done it differently and I am not interested in a diet of retread shows. It seems correct to me, from time-to-time, to do shows that attract some 40,000 people. That’s quite different from a retread which is a way to save money and come up with an exhibition. As far as I know Awash in Color: Homer, Sargent, and the Great American Watercolor (April 1993) was a much-appreciated exhibition. That came from our collection. When we do that it’s not limited. I’m not just showing things that are lying around. That would make no sense to anyone.

CG What I’m saying is, for now, have we seen the end of blockbusters? Considering the difficulties won’t it be some time before we again see something like Peter Sutton’s (1993) The Age of Rubens. As Alan Shestack told me, Sutton started working on that show from the minute he arrived at the MFA (1985).

Consider Monet in the ‘90s: The Series Paintings which Paul Tucker curated in 1990. It’s said that the museum had great attendance but didn’t make any money because the insurance costs were so high. On the other hand, Renoir in 1985, had a record attendance of some 500,000, and cleared $1 million for the museum. Between then and now costs have risen cutting into profit margins. Museums can only do those shows with corporate sponsorship. Shestack told me that he couldn’t find sponsorship for The Age of Rubens but believed in the project and took a chance. That gets risky and museums look more for a sure thing.

MR It doesn’t matter if shows make money or not as long as you know why you are doing them. I do not want to do exhibitions just to make a profit but we have to get the books balanced. We will put on some exhibitions that take a loss. That’s an attempt to balance the picture.

CG Exhibitions create interest in the institution as did Rubens last year. There is nothing on that level in the schedule this year.

MR Oh really. What about our Nolde show? Do you think that’s a worthwhile exhibition? It’s a great exhibition.

(Emil Nolde: The Artists Prints curated by Clifford Ackley, 1995, proved to be controversial because of the artist’s membership in the Nazi party. There was a contentious panel discussion at the Goethe Institute with emotional exchanges between the audience and panelists. The artist was presented as völkisch an adherent of a German ethnic and nationalist movement espousing “blood and soil” which was active from the late 19th century through the Nazi era. By keeping a low profile during National Socialism, Nolde was tolerated or ignored in a manner that other German expressionists were not. From critics there were no debates about the superb aesthetics of the exhibition. There were protests and headlines, however, that the artist’s Nazi background was not covered in the catalogue. The museum opted to add that information in wall text for the exhibition.)

CG Is there corporate support for the Nolde exhibition?

MR I’m not sure. Frankly, I’m running a museum with worthwhile exhibitions not developing projects to lure corporate sponsors. We want to do what we want to do. Nolde is a potentially wonderful exhibition. You seem to criticize the museum for doing exhibitions to make money and then are displeased when we do something superb like Nolde. It’s a wonderfully worthwhile opportunity.

(The backfire of Nolde’s Nazi affiliation was an unforced error of the curator. The question is whether Ackley knew of, but opted to ignore, the artist’s questionable politics. It underscores an era when the moral compass and sensitivity to social justice by curators and museums were less well calibrated.)

CG What we are discussing is the museum as a presenter of major exhibitions like those focused on impressionist masters. They attract record attendance and outreach. Niche exhibitions like Nolde are a part of the scholarly mix but on their own, as is the case currently, don’t accomplish goals for expanding and sustaining attendance, membership and income.

MR We need to do Renoir and Nolde. That’s very important.

CG Because of all the pressures of fund raising on museums it is interesting that some top curators, like Peter Sutton, leave for the private sector where they have more income and latitude. He was arguably frustrated not to get the Rembrandt show that he had initiated.

MR You will have to ask Mr. Sutton how he is getting along at Christie’s.

(Former MFA director, Perry T. Rathbone, joined the auction house for a number of years. What happens when top museum directors and curators lure great collections to the market rather than to museums? With changes in the tax laws there is less incentive for donations. There is logic to selling work which is then taxed or perhaps donated to charities. Many wealthy collectors, including museum trustees, acquire as an investment strategy. While the MFA’s curator of European Painting, Peter Walsh, the retired director of the Getty Museum, was a paid consultant to collector William I. Koch. An area of inquiry is the extent to which curators and art historians are compensated for attributions and finder’s fees. While regarded as unethical, it is common for curators to collect in their field and accept gifts from artists.)

Our curators have tremendous opportunities for what they want to do. You are generalizing based on one person. I have set my directorship from the time I’ve been here on the theme of One Museum. To not be a museum of separate departments but a museum of unity. The personality syndrome is subordinated to the museum and that’s an important change. I feel the mandate is as an educational institution. There is a focus on the integrity of the collections and their interpretation. We offer great opportunities in our own way.

(Five years later, in 1999, there was controversial clarification of what Rogers meant by One Museum. Until then a director presided over a number of departments, some world renowned, that functioned as independent fiefdoms. Some were powerful and well endowed with restricted funds. Some like contemporary art, which was founded in 1971, had limited staff and resources. The director presided over acquisition requests from relatively meager unrestricted funds.

Rogers was challenged by the power and independence of curators. They had prevailed in a cabal to oust Merrill Rueppel as director.

In what was later described by the media as the museum’s Boston Massacre the director struck quickly and decisively. The genteel aura of the museum changed forever. Emulating the manner of a corporation 18 curators were summarily dismissed and escorted from the building by security. Most notably this included two renowned curators of decorative arts: Jonathan Leo Fairbanks (28 years) and Anne Poulet (20 years).

Fairbanks is now retired as director of the Fuller Craft Museum. Poulet has retired as director of New York’s Frick Museum. As a part of her dowry Poulet brought to the Frick the major exhibition of the sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon which she worked on for the MFA.

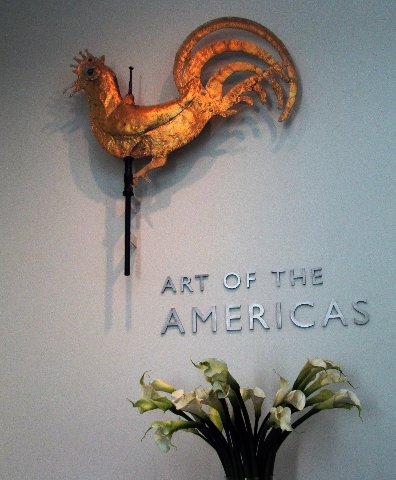

In a massive overhaul ignoring media delineations, such as painting and sculpture, prints and drawings or decorative arts and furniture, mega mergers were defined by geography.

For a three-year period under Jan Fontein, the reach of Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. included European and American Painting and Contemporary Art. He was John Moors Cabot curator of American Art when Rogers appointed him chair of the new Art of the Americas department. Several months later he resigned in protest and left to found the Department of American Art for the Harvard Art Museums)

CG What do you have in mind.

MR Museums tend to focus on painting but I would like to do more with three dimensional objects and non-European cultures. I think eventually we may get away entirely from just painting shows. We can definitely do more with contemporary sculpture.

CG Why are we missing shows like Rembrandt?

MR That’s got a lot to do with funding. We need individuals and corporations to give to us and trust us.

CG Recently I was surprised to see The Head of Sesostris III, a masterpiece of Middle Kingdom art, on view in the Egyptian galleries on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

MR We have a regular policy for such exchanges. Some things we are sending to Florida for the winter.

CG It used to be less vibrant but there have been changes. The former MFA curator, Ken Moffett, for example is director of the Ft. Lauderdale Museum and has done interesting programming.

MR It is important to have the collections more widely seen at Nagoya and other museums.

CG That’s the argument of Tom Krens in creating satellite museums. He states that 85% of the collections of major museums like the Guggenheim are not on view. In recent years there have been some great exchanges. When the MFA was renovating it sent its Copley’s to the Philadelphia Museum. Similarly, when they were under construction, a great show of their Thomas Eakins collection came here. Do you see more of those kinds of exchanges?

MR We shall see. I am just getting started and it will take some time moving forward to create a dynamic exhibition program.

CG Do you come from money?

(With benefits and raises his compensation was some $900,000 annually. When visiting as a job candidate he was put up at the former Midtown Motor Inn near the museum. There was a dinner with trustees at The Ritz that has been described as brilliant.)

MR Myself? I’m afraid not. I was born on 20 acres in a Yorkshire hamlet. My family were farmers and butchers. If you wanted me to, I could break down a hog from hams to sausages. But I don’t want to be known as the “butcher of the MFA.”

CG What’s your personal style regarding leisure time. Do you like to cook and entertain?

MR I don’t have time to cook and am not a creature of habit. There is not a regular day when I do the shopping and errands.

CG Boston has long been regarded as an anglophile city.

MR I’m not coming here because it’s a city like London. I’m coming because there are wonderful opportunities and challenges. I’m paid to run the museum and a part of that job is to mingle with individuals who support our fundraising.

I have a small house in the Back Bay which is not suitable for entertaining. I felt that if I come to Boston I want to be a part of the city. There was temptation to live in one of the towns around but I want to be where I can walk to work and to theatre. Back Bay is near the shops and entertainment.

(The museum later provided housing in Newton suitable for the entertainment of donors and dignataries expected of a museum director.)

CG Talking to museum directors and curators there seem to be different models of how exhibitions are organized and marketed. Generally, that entails finding corporate sponsors. But that appears to be changing. Given the startup costs and touring, with a catalogue, a show may tour for a year or two. Different approaches are emerging with video and on line marketing. Do you see a shift in that direction particularly for funding major exhibitions? It appears, particularly with international projects, that potential media and marketing is a part of the initial stages of exhibitions.

MR The first thing I would say is that there is much more planning in terms of corporate support. We have to put a lot more thought into this. Corporations seem much more interested in health related and content related giving. What we have here is great resources for education. It’s at the very heart of new ways of getting corporations involved with exhibitions. We have to plan further ahead and with them. They have to see potential in exhibitions and have their demands met as well. The technological and media applications of exhibitions are very important. We are looking at ways in which information can be electronically published.

CG The Getty has been proposing projects to digitize museum collections. The goal would be to have images of objects on line. Eventually, one may make virtual tours of major museums. That would be a great resource for curators organizing exhibitions. There has been a decline in federal and state funding. Given this environment all of the cultural institutions are seeking the same private and corporate sources. There are many mouths to feed.

MR To succeed in attracting corporate support we have to give them something that they want. If we can do that, we will be successful.

CG It was before your time but what is your opinion about why the museum was not successful in securing support for its Rubens exhibition?

MR It’s a matter of creating opportunities for them. Rubens did have opportunities for the right corporation. The elements are there and we have to find the right match.

CG What is your position on contemporary art?

MR We will be doing an extraordinary number of special exhibitions. It’s very important to grow that collection. We have to be showing what we have to showcase contemporary art acquisitions to make the case for attracting more giving.

CG It’s well known that the MFA is a museum with world class collections but not in 20th century art.

MR I understand that but think that there are a lot of things that can be done. We have significant support for the contemporary department.

(When a respected curator Trevor Fairbrother left search for top candidates was unsuccessful. Established curators were wary of reporting to Rogers. The position was filled by Cheryl Brutvan from the Albright Knox Museum. Her programming was regarded as less than remarkable. Eventually, she left for the Norton Gallery. In 2011, Edward Saywell became chair of the Linde Family Wing for Contemporary Art with Jen Mergel as the Beal Senior Curator of Contemporary Art. Currently, Reto Thüring is the Beal Family chair. Saywell is now Chief of Exhibitions Strategy and Gallery Displays.)

Interview September, 2011, opening of the Linde Wing of Contemporary Art.

Charles Giuliano Is there anything left to do?

Malcolm Rogers The museum is like one of those huge bridges. You start painting at one end and by the time you reach the other end it’s time to start all over again.

CG You’ve had so many projects.

MR I like new things. What a privilege it is to be here during a time of transformation for the museum.

CG How long have you been here?

MR Sixteen or seventeen years I can’t remember. I’m about the fourth longest serving director.

CG In terms of bricks and mortar also one of the most significant.

MR When you think of it for a museum of this size to have transformed every single façade in a period of four or five years.

CG Let’s talk about contemporary art. This was the major museum which was famous for not having any.

MR We’ll have to see what you think. It’s definitely new.

CG What have you acquired in the past few years?

MR There’s a lot that we’ve acquired. But I’ve also said there’s a real culture of collectors in town that’s growing up. People are backing purchases. Boston is in a process of exciting change.

CG How did that come about? Boston historically has been a city that didn’t have an interest in contemporary art.

MR It has gradually been gaining momentum. If you think about all the institutions there are in town. Think of the influence of the new ICA.

CG Are you going to work together?

MR Of course. If you look at the labels on the walls you will see that many of the benefactors are supporters of the ICA and the MFA.

(In 1988 the MFA and ICA jointly presented The BiNational: Art of the Late '80s in cooperation with the Stadtische Kunsthalle and the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen of Dusseldorf and with support from the Mass. Council on the Arts and Humanities, AT&T Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts.)

CG In New York there has been an interesting relationship between MoMA and the Met. When works in the MoMA collection morph from contemporary and modernist to historic some of that material gets transferred to the Met. The ICA is starting to collect but has little or no space to store more than a token of work. In a generation or so it will reach a critical mass and perhaps a crisis point. Can you see some of that work finding its way to the MFA using the model of MoMA and the Met?

MR We don’t have that relationship at the moment. We have art going back thousands of years. When things grow older, they become just as attractive to us.

CG What is your own definition of contemporary art.

MR My own, very personal definition is anything that was produced during the lifetime of the oldest person in the room.

(The MFA’s Linde Family Wing for Contemporary Art includes Claude Monet’s "La Japonaise" (Camille Monet in Japanese costume), 1876, as a conceptual aspect of a work by Louise Lawler. And “Rape of the Sabine Women” by Picasso, 1963.)

CG That’s an interesting definition. I haven’t heard that before.

MR I think there is too much emphasis on cutting edge and bleeding edge and wet paint. But I think it should be the art of a generation.

CG The issue is that contemporary art has evolved beyond the object with installations and the epic scaled works that we see on the global circuit of biennials. Much of that work just simply can’t be housed in the galleries of the MFA. We are only viewing the object-oriented slice of contemporary art in museums. Has that informed the mandate of what is contained here?

MR I think we have some pretty ambitious installation pieces here. When we are acquiring something, we have to ask will it stand the test of time artistically? Is it conservationally sound? Will it last? Does it stand a chance of coming out historically? You’ve also got to show imagination. You’ve got to love the subject. That sometimes allows you to make risky choices. Contemporary art is about risky choices to some extent.

CG How do you preserve an Anselm Kiefer? You have one actually.

MR Yes, we do have one with straw built into it. Conservation is very difficult.

CG That was a risky piece when it was acquired.

MR I’m not saying we’ll stop taking risks. I think you will see some risks around the walls. There are some things that are very conservative and quite New England.

CG Is this a good day for you Malcolm?

MR It’s an exciting day. I always love to see a project coming to fulfillment. The truth is it’s never complete. This leads on to other opportunities. I’m particularly happy because everyone involved in this project, it wasn’t a huge budget, everyone has a real sense of joy and achievement in the project.

CG Particularly having works to put on the wall and not fall flat on your face. Why has this historically been such a problematic aspect of the MFA’s collection?

MR We are what people in Boston collect. To a very large extent. Certainly, people from other cities are giving us art. In truth a city collection like this is a reflection of its donors. The taste in Boston has been fundamentally conservative. Now things are perking up.

CG In the 19th century, during the era of French Impressionism, Bostonians were progressive and made great acquisitions.

MR That’s absolutely right.

CG Then it tapered off in the early 20th century when business and banking in Boston lost momentum. The taste of old money was ever more conservative. In recent years there had been a boom and new entrepreneurship.

MR Yes, so we are in a way a reflection of the taste and mood of our city. This is an exciting time.

CG What happened when the focus of the Boston art world turned to immigrants in the 1920s and the Depression years of the 1930s? Boston collectors and the MFA passed on the era of the Boston Expressionists

(Ellsworth Kelly during the Linde opening discussed studying with Karl Zerbe at the Museum School.)

MR You know that these are artists whom we have on display in the museum. Just remember that we are one of the world’s great encyclopedic museums. We have to have a bit of everything. We can’t be a museum of New England. We work as hard as we can for New England artists as well. Just look around.

CG You have depth in Copley. The interest in contemporary Boston art tapered off from the 1920s until only comparatively recently. During the 1920s Boston Impressionists like The Ten were phasing out and the immigrant Boston Expressionists were emerging. It is precisely when the mainstream of Boston lost interest not just in Boston artists, but also passed on Post War abstract expressionism, pop, minimalism and other contemporary movements. Are you now picking up and coming back to multi-culturalism?

MR As you know multi-culturalism is an important theme in any encyclopedic museum.

We’re conscious that work has to be done in the Twentieth Century and in the contemporary period. You’ll see in these galleries a statement of good intentions. Some achievement. More still to do.

CG A way to go.

MR There’s always a way to go. There’s always a way to go.

CG Are you under pressure for that? What is your relationship with the National Center for Afro American Artists and the MFA’s adjunct curator, Barry Gaither?

MR It’s good. We see Barry here a lot. He works very actively with the museum. It’s a source of great interest to us. Watch this space. You’ll hear news of interesting acquisitions. What we are presenting here is a salad bar of things you will love and things you won’t. The idea is to provoke discussion.

(Re "Watch This Space" the museum soon after announced plans to acquire "Man at His Bath" by the French Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte (1848 – 1894.) The artist inherited from his father in 1874 and his mother in 1878. It allowed him to work as well as collect and support other artists. To purchase the Caillebotte, the museum sold works by Alfred Sisley, Maxime Camille Louis Maufra, Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro.)

CG Is there anything you are particularly pleased with?

MR What I am particularly pleased with, which benefits the whole of Boston, is that Boston is acquiring collectors of contemporary art. They are prepared to work with more than one institution which I feel is critical. It creates a scene here. Looking historically at what you will see here today I am particularly pleased by the acquisition of a major work by Ellsworth Kelly. It’s something we lacked and he is one of the greatest alumni of the Museum School.

CG Can you ever fill the gaps?

MR I would like to fill the gaps. There will still be opportunities to fill gaps in the next decades. As work is reassessed and things come on the market when collections break up. We’ll be active.

CG This week MoMA is opening a deKooning exhibition which, with works valued at more than a billion dollars, is the most expensive project the museum has ever undertaken.

MR We just acquired our first deKooning painting. It’s a comparatively small work but a beautiful head study. Perhaps one day deKooning’s prices may come down and we’ll have an opportunity.