Compagnie CNDC-Angers/ Robert Swinston

Celebrating Merce Cunningham Centennial at Jacob's Pillow.

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 08, 2019

Compagnie CNDC-Angers/ Robert Swinston

Jacobs’s Pillow

Ted Shawn Theatre

July 3-7, 2019

Artistic Director: Robert Swinston

Dancers: Matthieu Chayrigues, Anna Chirescu, Pierre Guibault, Gianni Joseph, Catarina Parnao, Flora Rogeboz, Carla Schiavo, Claire Seigle-Goujon

Suite for Five (1953-1958)

Choreogrtaphy: Merce Cunningham

Reconstruction: Robert Swinston

Music: John Cage “Music for Piano 4-19”

Musician: Adam Tendler

Costumes: Robert Rauschenberg

Inlets 2 (1983)

Choreography: Merce Cunningham

Reconstruction: Robert Swinton

Music: John Cage “Inlets” (1977)

Costumes and Lighting: Mark Lancaster

Costume execution: Catherine Garnier

How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run (1965)

Choreography: Merce Cunningham

Reconstruction: Robert Swinston

Music: John Cage stories from “Indeterminancy”

Costumes: Michelle Arnet

Readers: Laura Kuhn and Adam Tendler

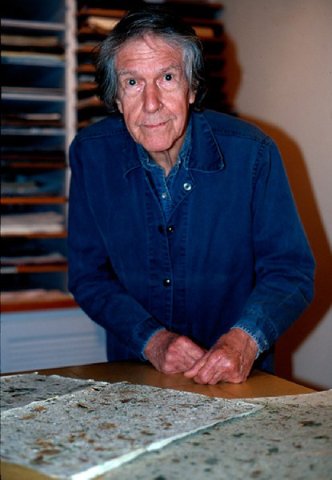

For his centennial Jacob’s Pillow presented three dances by the avant-garde choreographer Merce Cunningham (1919-2009). The “music” featured his collaborator and life partner John Cage (1912-1992).

In July, 2009 we attended the final performance at Jacob’s Pillow by the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Too ill to attend there was a live video feed which he viewed. Several days later, on July 26, he passed away.

In accordance with his will the company toured for the next two years. That ended with three performances in New York including New Year’s Eve at the Park Avenue Armory. In compliance with his wish tickets were just $10 each.

The long time Cunningham dancer and associate Robert Swinton was the artistic director for that endgame.

Not long after the final performance Swinton was hired as director of Centre National de Dance Contemporaine (CNDC) in Angers, France. In 2013 he founded Compagnie CNDC-Angers, the Center’s resident dance company.

With its combination of ballet and the upper body movement of modern dance he trained the company in the Cunningham technique. With intimate knowledge of the repertoire he reconstructed works of which three were presented at Jacob’s Pillow.

That was a complex process. The early work preceeded the era of routine video documentation. In the Cunningham archive were hand written notes all of which were not decipherable. By disbanding the company it is not evident that the choreographer intended to preserve the oeuvre. Many companies may change but continue to perform under new artistic directors.

Individual works performed by other companies may be documented and preserved. But the legacy as a whole of Cunningham/Cage was questionable.

That made the program we experienced at Jacob’s Pillow all the more palpable and historically resonant.

The intangible aspect of the experience was that, while academically correct, it lacked their whimsy. To see Cunningham/ Cage in performance or video documentation was to imbibe in the intoxication of their mischief.

They were serious creators but with humor and irony. This is directly evident in the overlapping, clear and contradictory, recitation by two narrators for the final piece How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run. The text is full of deadpan anecdotes and absurdist humor. That’s in the dada tradition of Marcel Duchamp from whom Cage drew inspiration.

In the early days of the company they drove around in a VW bus. It was the era of Black Mountain college where they recruited the young art student Robert Rauschenberg. He designed costumes and sets that had to fit into the van. They were inspired by Duchamp, his aesthetic puns, and jokes.

With chutzpah the young Rauschenberg asked Willem de Kooning to give him a drawing which he meticulously erased. He also exhibited several vertical, grouped blank canvases. Cage countered by famously composing a piano piece with four minutes and thirty three seconds of silence.

When asked by an audience what he felt about people coughing during the piece he responded “I would listen to that.” That underscored his notions of sound as music.

Cage, in addition to dada and the European avant-garde, was also interested in Eastern philosophy. That entailed using the ancient I Ching oracles and its 64 hexigrams in creating works of art. He and Cunningham used “chance operations” to create works. They predetermined 64 variations and selected from them by rolling dice.

While seemingly arbitrary, by leaving choice to chance, they liked how that opened a range of possibilities. Success, in the usual sense of pleasing an audience and critics, was not their intention. One approach to experiencing their work is to apply Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle.

It was exhilarating and challenging to experience/ endure an evening of Cage/ Cunningham. One of their signifying mantras was to be separate but equal. While sound and movement are presented simultaneously there is no evident co-dependency. One can listen to and focus on the sound of Cage or follow the movement of Cunningham’s austere choreography.

Even the dancers function for the most part independently. In Suite for Five, for example, each of the dancers appears to solo. Even when more than one dancer is on stage there is no partnering. There are mostly legato movements of stretching, extension, turns and sweeping gestures. The sound entails a “prepared” grand piano. Screws and other materials are wedged between strings. The player both strikes the keyboard and reaches in to play in a pizzicato manner. Cage commented that he composed the music based on imperfections of the paper.

For Inlets 2 we were intrigued by three musicians playing a table of conch shells of varying size from small to quite large. The shells contained water. By manipulating them microphones amplified their gurgling sounds. I had seen them played in videos but this was my first “live” encounter. Again it was a coin toss, something they would enjoy, between listening or looking.

As a young dancer Cunningham was a part of the Martha Graham company. It will appear at Jacob’s Pillow this season. She was the foremost American modern dancer of her generation. Her narrative choreography entailed strong emotion and expression of an American vernacular.

When Cage encouraged him to leave and start his own company, in a sense, Cunningham purged himself from Graham. While Cage developed sound the dance of Cunningham concentrated on movement.

In a video it was fascinating to see them improvising together. Cunningham with a erect, signature posture, executed a series of gestures forming a pattern of movements. It was tense and contained. Seated before a microphone Cage flicked a feather over the needles of a cactus plant. They were intently aware of each other while also focused and self contained. At the conclusion of the sequence there was a hearty burst of mutual laughter. Their pleasure and amusement was richly enjoyable to witness.

There was a sense of child like delight in seeing just how far they could push an audience getting away with their merry pranks. It’s ok to laugh with but not at them. Yesterday, however, in their absence it seemed excellent but too serious.

There was relief in the final piece How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run where mirth poked through. As the title implies there was a sense of a game. But with no rules, discernable patterns, or even common sense. The casually attired company of eight dancers wore colorful tops and pants. Although we never figured out the game the dancers were having fun. It was enjoyable to see them relaxed and smiling.

The dance started with a pop. One of the two narrators, Adam Tandler, opened a bottle of champagne. He poured a glass for himself as well as Laura Kuhn. By the end of the piece the bottle was empty. There was a laugh when a male dancer stopped by for a sip.

It is hard to imagine how the dancers responded to dual readings of a Cunningham speech. One could unscramble bits and pieces but when they spoke together there was a blur of sound. We discovered that they repeated each other. Typically, Cage was a name dropper and some anecdotes reference to his mentor, the Zen master Dr. D.T. Suzuki. I have heard other versions of the anecdotes but not the outrageous ones about Cunningham's eccentric mother.

We are grateful to have had this experience. Of greater significance, however, it was reminder of the spirit of Cage and Cunningham. Mirth, whimsy and reliance on chance is their enduring legacy. Homo Ludens, man the playful, is an ancient concept and creative force in the arts. As these merry pranksters continue to remind us it is better to laugh than cry.