Ivo van Hove's The Damned

Hatred as Source of All Evil at Park Avenue Armory

By: Susan Hall - Jul 21, 2018

The Damned by Ivo van Hove, based on the screenplay of Luchino Visconti, tears through the Park Avenue Armory. The stage is in four parts, if you don’t include a scene which goes out onto Park Avenue where a shocked dog walker sees the mad Sophie von Essenbeck running wildly in search of her son.

Rituals of sexual predation are portrayed stage right on beds behind which are a row of mirrored tables. Behind them on a riser are seats where actors who are not immediately engaged in a scene watch the proceedings.

Stage left are caskets which are not at Dachau where some of the characters in the play are burned even before World War II starts. Burial rituals takes place here, often accompanied by dirge music on an organ. Music in the show ranges from a beautiful soprano solo to heavy metal.

In addition to the rituals taking place on both sides of the stage, an active LED screen at the back of the stage displays image. Predatory camera operators peer into the faces of the actors, blowing them up for us to examine. We can not avert our eyes. In these images, the actors have no chance to adjust for the camera. Often the faces are contorted and distorted not for the best camera angle, but to reveal the extreme emotions the actors have dredged up as they express their characters.

There is no escaping the cameras. In fact, lights-up moments breaking up scenes reveal the audience on the screen, where we too become complicitous in this drama.

The main action takes place on an orange-floored stage designed by Jan Versweyved. It reflects fire everywhere. The burning of the Reichstag opens the film. We do not see the Dachau furnace fires, but surely the floor also captures the color of their heat.

Werner Herzog’s Lessons of Darkness, a documentary on the Gulf War in which the beautiful orange of oil fields on fire, is mesmerizing. The score for this film was Wagner, whose final opera of the Ring Cycle bears the title, The Damned, translated from German.

Wagner is showing us the end of the world as the Gods knew it. In the Visconti take, we are in the lead up to WWII in Germany in the home of a family who are modeled on the German armament aristocrats, the Krupps.

The only son of Alfred and Bertha Krupp was arrested on the Isle of Capri where he was being entertained by 40 adolescent boys. There was no history of in-breeding. In fact the Krupps and Visconti’s imagined family, the Essenbecks, try hard to breed out. Yet this does not help character.

The great Belgian imagist van Hove goes to the heart of the matter, hatred. He is known for stripping away all but the emotion from character. We dive quickly into the consequences of the Essenbeck heir Martin’s perversions, fanned by his mother’s taunting efforts to put him in a wig and makeup. Visconti opens his film with Martin in drag like Marlene Dietrich in Josef von Sternberg’s 1930 film Blue Angel.

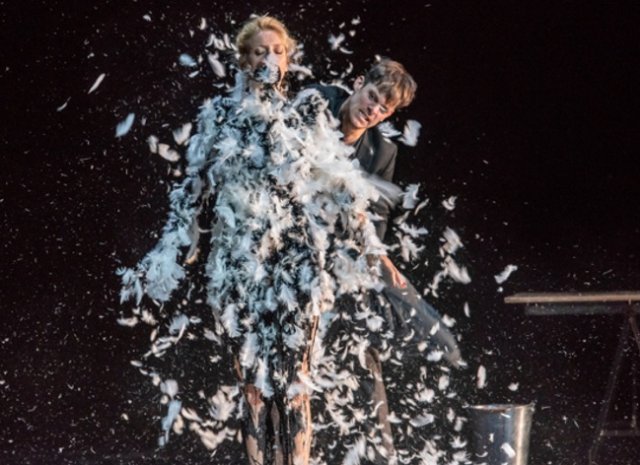

Christophe Montenez of the magnificent Comedie Francaise troop that enacts this theater, is a Martin more harlequin, dancing across the stage as he performs in a sequined jacket. He slithers balletically, as he will through the evening in the predation of his cousins, a young Jewish girl and finally triumphantly, his mother. Martin is the heir to the Essenbeck fortune, at first an unlikely candidate for power and finally the perfect Nazi.

Sophie, an arresting Elsa Lepoivre, starts out as Lady Macbeth, the widow of the Essenbeck heir who died as a hero of WWI. She slinks, sometimes sulking in the background, waiting for events to unfold. At other times, she is magnificently powerful, an active participant advancing the drama as she improves the prospects of her lover, who only gains the family name through a minute-long marriage.

During the brief marriage ceremony, Sophie is asked if she is Aryan. She replied yes, recalling the humor some common Germans found in this question, to which they answered yes. If being Aryan means being tall like Hitler, blond like Goebbels, and lithe like Göring .

Sophie is finally controlled by her son, Martin, who seeks vengeance based on hatred, the prime emotion von Hove has elected to expose.

View from the Bridge, van Hove’s production of the Arthur Miller play, was made relevant by van Hove’s exposure of emotion. In The Damned, using hatred as the prime prompt may take away from the story’s historical relevance.

Yet artists have every right to reinterpret great underlying works of art. Van Hove has done this with The Damned, following Visconti’s story line, and deliberately denying himself the film as initial prompt. For him, the consequences of hate are what we need to look at.

Recently at Dachau, these consequences resonated. In the Armory on the lip of the stage, spigots symbolize the emission of lethal gasses and an urn into which the ash-remains of humans we have come to know during the evening, are dumped. The work’s final image is of the consummate Nazi, Martin, covered in these ashes.

The Night of the Long Knives is created with two live figures on stage and images of the homosexual orgy at first live on screen. Killed, the dead figures are sprawled out in Matisse-like outlines. The sturmabteilemgen (SA) which an Essenbeck family member led, is shown with all its militant masculinity and homerotic overtones. Providing emotional shelter, it compressed many repressed conflicts of German society.

Novel and starkly disturbing choices include the dying of live people in caskets, and the seduction of young girls by Martin. The reverse black and white images of Martin’s seduction by and with his mother are blown up on the screen in the ghostly cast of couples past, like Oedipus and his mother.

Germans have nobly faced this part of their history. We have come to see that Hitler's rise was caused as much by habit, confusion, self-interest, fear and distraction as it was by the depravity of aristocrats. Yet depravity and hatred makes better theater.

What a rich and wrenching evening van Hove has mounted. Park Avenue Armory is the perfect venue to explore this incredible theatrical conception. We are compelled to engage during the show and afterwards.