The Chinese Lady by Lloyd Suh

Barrington Stage and Ma-Yi Theatre Company

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 02, 2018

The Chinese Lady

By Lloyd Suh

Directed by Ralph B. Pena

Scenic/ costume designer, Junghyun Georgia Lee; Lighting, Oliver Wason; Composer/sound, Fabian Obispo

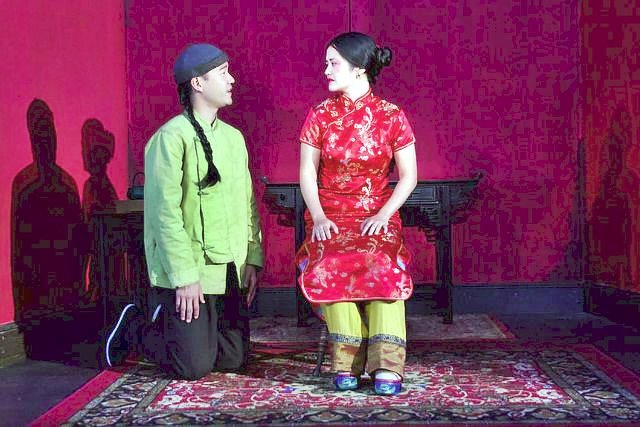

Cast: Daniel K. Isaac (Atung), Shannon Tyo (Afong Moy)

Co production of Barrington Stage Company and Ma-Yi Theater Company

St. Germain Stage

July 20 to August 11, 2018

There is a large shipping container at the center of the stage. In dim light it is rotated. Atung (Daniel K. Issac) prepares the set change. Thin curtains, of non descript color, are drawn in framing the box and its wing doors from either side.

With an “aha” moment the lights (Oliver Wason) brightly illuminate “The Room.” It is tackily ornamented with a 19th century entrepreneur’s notion of kitschy, curio shop Chinoiserie.

That term derives from 18th century French furniture and decorative arts when such objects were imported by the court. The best examples of Chinese porcelain were so expensive that Madame De Pompadour founded the Sevres pottery industry as a patriotic investment.

The American fad for Chinese exotica was launched in 1834, when Afong Moy (Shannon Tyo), arrived in New York allegedly at the age of 14. The youngest of seven, she was sold for two years to New York-based Far East importers Nathaniel and Frederick Carne. She was exhibited at Peale's Museum. Long after the contract expired she performed twice a day, Tuesdays through Sundays.

For two bits, ten cents for children, the rubes could hear her speak, through Atung as interpreter, about her culture, food, manner of using chop sticks, and other ephemera. Part of the presentation entailed circumnavigating the restricted space on tiny bound feet.

There is a gruesome description of how the bones of children were repeatedly broken and bound to make a girl more helpless and feminine. It is just such atrocities and malformations that drew audiences to horrendous freak shows. As a child it’s something I experienced in the side show when the circus came to town.

While Chinese “Coolies” sought their fortune in the California Gold Rush of 1849 no women emigrated. For decades that made Afong Moy exotic and unique. At the peak of interest her display cost seventy five cents and fifty cents for kids. There was a forty city tour and an audience with the “American Emperor” then president Andrew Jackson.

She was sold to P.T. Barnum who eventually replaced her by purchasing another teenager. Atung, with no other skills or means of income, was retained as interpreter and care provider.

The play by Lloyd Suh, as directed Ralph B. Pena, is as constricted and confined as the bound feet of Afong Moy. The dramatic action is so limited and repetitive that it becomes ever more enervating. That equates to a very long, one act, ninety minute play.

A part of that is the playwright’s device of conveying the tedium of endless sameness of performance rituals and how that plays out over years that stretch into decades.

Initially speaking no English, and with restricted mobility and no money, we wonder about the time frame of her dialogue. As she ages and becomes more fluent there is a commentary on American and world events.

The aging process is mostly accomplished through inventive lighting by Wason. The cubicle/room is darkened then lit from a different angle. That ends with a staggered fade out. By then she is in her 80s and there is even a stretch as an ancient spokesperson in 2018.

In a sweep and leap of faith Suh has stretched out the narrative to become an analogy for the current disaster of immigration in America. During the last third of the play Afong Moy provides harrowing accounts of the fate of Chinese laborers who were the primary workers of the Transcontinental Railroad. It was difficult work with many casualies. Part of it entailed blasting through mountains. The men sent meager money home to their families.

The golden spike that connected the coasts was driven on May 10, 1869. After that Chinese labor was expendable. There is a vivid recounting of numerous slaughters including castration and lynchings.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers. The act was initially intended to last for 10 years, but was renewed in 1892 with the Geary Act and made permanent in 1902. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first law implemented to prevent a specific ethnic group from immigrating to the United States. It was repealed by the Magnuson Act on December 17, 1943.

In the Age of Trump what about that sounds familiar?

If the intention of Suh was to present social justice theatre there is a curious and tedious end around. It is a thumper to have such a restricted character take on the task of being a spokesperson for an atrocious chapter of American history.

We are not at all clear about how she survived to a ripe old age particularly during the struggle of the post Barnum years. The playwright provides her with implausible longevity as well as an heroic persona. You can drive a truck through holes in the narrative.

Within the limits of what they are given the performances are credible. Isaac presents a caricatured subordinate role. He moved the props around but, by definition, is a non person. Even he presents himself as an enigma. We never know how he came to be fluent in English or how he got the room and board job. There is a hint of romance which was quickly snuffed. Their relationship, other than one of necessity, is never established.

Overall, he was better off than working on the railroad.

The performance of Tyo has engaging moments. Her persona is a delicate, stylized cultural amalgam. Initially, she is just a precocious teenager, lost and bewildered, someone to view with racist curiosity. It is subtle and challenging to morph into a grasp of social and political awareness.

It is for this latter aspect that the production will be respected and find an audience. Eventually, the two hander developed a voice but mostly The Chinese Lady was little more than a side show.

To pursue the history we recommend the books of Maxine Hong Kingston particularly her China Men and The Woman Warrior. It’s essential reading for all Americans.