Pelléas et Mélisande

Santa Fe Opera's Take on a Brooding Tale from Debussy and Maeterlinck

By: Victor Cordell - Aug 05, 2023

When Claude Debussy discussed a prospective opera libretto, he said that he sought a poetic source in which characters seemed out of place, out of time, and only half disclosed. For “Pelléas et Mélisande,” he found his soulmate in future Nobel Prize winner Maurice Maeterlinck, whose opaqueness suited Debussy so well that he adapted the playwright’s work almost verbatim except for modest trimming. The fit of the composer’s music with the play was fortuitous as it resulted in Debussy’s only completed opera.

In literary terms, “Pelléas et Mélisande” was the apotheosis of Symbolist opera, a somewhat ambiguous idiom with a reverence for language unbound by traditional meaning, with links to the delight of unnamed things and the mysticism of sound that becomes associated with them. Things are not what they appear to be but have a deeper meaning beneath the surface. The work is also full of symbolism with its metaphorical representations. Notwithstanding, the many symbols depicted are sometimes indecipherable. While many questions can be asked about this work, there are few answers that are absolutely right or wrong.

Musically, Debussy was a contemporary of Puccini, but his musical vocabulary in opera differed greatly. The Italian maestro penned many set pieces like arias, ensembles, and choruses replete with distinct and memorable melodies having wide musical range and leaps.

No stranger to melody, Debussy’s most famous pieces were the lush “Clair de Lune” and “Prelude of the Afternoon of a Faun.” Constrained to a fixed libretto that was not designed to accompany music limited the scope for musical expression in his opera. Thus, Debussy followed Wagner’s thesis of continuous melody with a tighter melodic line, more akin to lengthy but more tonal recitative. Without a chorus or large groups of principals on stage, Debussy’s work plays much like a chamber rather than a grand opera.

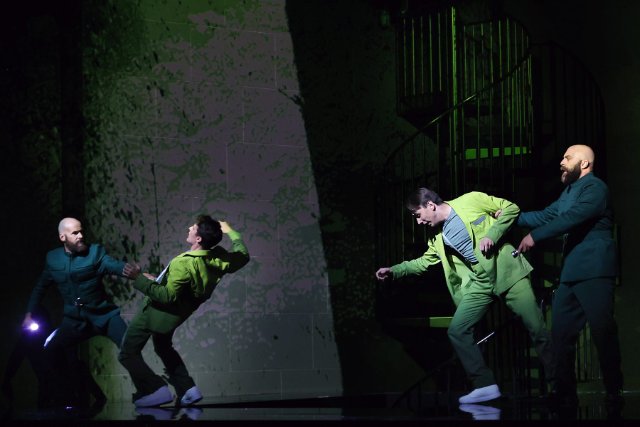

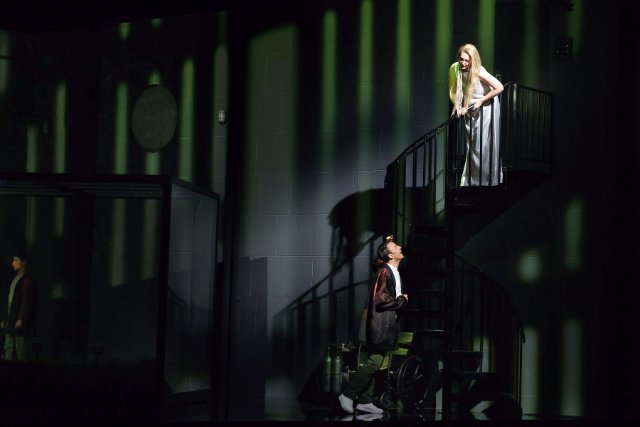

The resulting work however was a landmark in turn-of-the-century opera that is conducive to broad staging interpretation. Santa Fe Opera’s detailed and provocative rendering commands the attention and fascinates throughout. Director Natia Jones deserves immense kudos for also designing the complex scenery and projections, as well as costumery. Her only artistic design collaborator is D. M. Wood who is responsible for the also impressive lighting. The overall staging concept is brooding to match the unbroken darkness of the storyline.

The summary narrative of “Pelléas et Mélisande” is simple and well trodden. A prince, Golaud, finds a feral girl, Mélisande, in the forest and marries her. She and her husband’s younger half-brother, Pelléas, fall in love. People die. The end. Fortunately, considerable stimulating drama occurs along the way

Dyadal conflict within a group of well-differentiated characters drives the plot. Performances and voices excel across the board. Central to the clashes of desire is Mélisande. Haunted in character and with a haunting voice, Samantha Hankey portrays the innocence and beauty that trigger the hormonal reaction in the male siblings.

Knowing almost nothing about Mélisande and knowing that they don’t necessarily fit well, Golaud nevertheless takes her as his wife. While tolerant at the outset, he becomes increasingly hostile, symbolizing the abuse of the weak by the powerful, even using his son Yniold as a weapon of his oppression. Gihoon Kim is chilling as a conflicted tyrant who often intends well but struggles mightily with his urges. His emotive, mournful voice equally expresses his pain and his rage, and his portrayal is commanding.

The third member of the triangle is Pelléas, deftly portrayed by Huw Montague Rendall, a youthful sounding baritone in fine voice. In contrast to Golaud, Pelléas hesitates and long withholds his expression of love to Mélisande in spite of its long simmering.

This production is blessed with an exceptional cast of secondary principals. Raymond Aceto is King Arkel. We don’t know if his character has transformed as he readies for death, but for a royal, he is accommodating and empathetic. He holds special concern for Mélisande, despite the fact that her marriage to Golaud upset the king’s plan for a strategic alliance. From the opening words of the opera, Aceto demonstrates his booming resonance and range while he looms as a shell of past power.

Santa Fe treasure Susan Graham plays Geneviève, mother to the half-brothers. The role is small for an artist of Graham’s stature, but she displays both ideal presence and voice. Tweener Kai Edgar is Yniold, the son of Golaud. He is on point as the scared little boy with his penetrating treble (boy soprano) voice.

A dominant metaphor in the Symbolist narrative concerns water. Variously, a body floats in it; a crown falls into it; a ring is lost in it; hair is draped upon it; and the nose is offended by its acrid odor. What does it all mean? Who knows? It’s up to the observer. It could relate to transition or in some cases sexuality. A likely interpretation is that it has to do with danger or threat, but why should that be a focus of the story? Only Maeterlinck knew for sure.

If the libretto doesn’t create enough ambiguity, the staging adds to it. Gloominess and dim lighting signpost this production’s stage design. A flat, gray set acts as the receptacle for changing, colorless projections that dominate the visual field. Three circulating fans appear as part of the fixed set. Are they figurative, fanning the flames; functional, cooling the stage; or something else?

Another directorial conceit involves sometimes having doppelgangers in twosomes on stage. Often, the actions of the two sets of identical characters is the same, but at other times, they diverge. Do the replicants represent alter egos? Do they depict the differing perceptions of the two characters in their relationships? Probably the latter, but who knows?

In any case, this opera fulfills Debussy’s mystical quest, and this outstanding production offers plenty of entertainment and plenty to think about.

“Pelléas et Mélisande,” with music and libretto by Claude Debussy and book by Maurice Maeterlinck is produced by Santa Fe Opera and plays at its home at 301 Opera Drive, Santa Fe, NM through August 18, 2023.