Louise Bourgeois at the Gropius Bau

Berlin Displays The Woven Child

By: Susan Hall - Aug 08, 2022

The late work of Louise Bourgeois is on view at the Gropius Bau in Berlin. The overwhelming space, high ceilings, light curators will let it in, never makes Bourgeois seem small. Perhaps a point.

Instead the massive rooms draw you to classic forms in their stillness. Whatever turbulent emotions originated these works are quelled. Viewers can re-awaken them personally.

As you step into each new room, an object intrigues. You rest and absorb. Objects invite one by one scrutiny. I circle once through slowly, and then reverse direction even more slowly. Drawn in by the artist, I knew I could spend much more time with her. She speaks to women. You want to absorb her sculpted messages visually and viscerally.

Bourgeois started life in Paris where her parents restored antique tapestries and sold them in a gallery. Her mother we now know as Mamam, a giant spider cast in various incarnations at Storm King, New York and the Guggenheim in Bilbao, The National Gallery, Ottowa and many other locations.

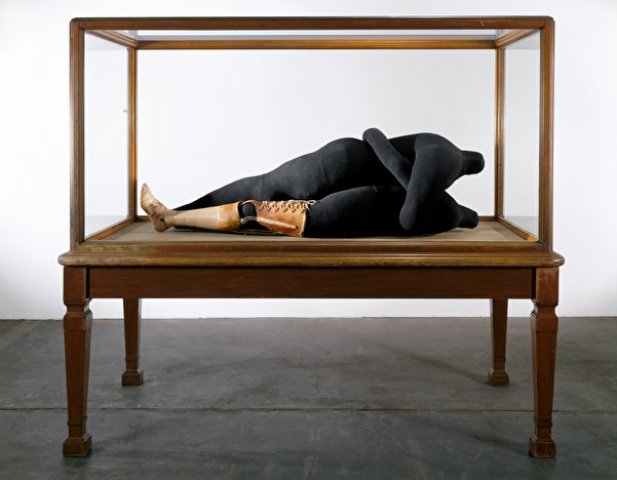

In Woven Child Bourgeois often encases a sculpture in a cell. Cells are scaled to the size of the rooms in her Chelsea home. They contain possessions in this show, articles of clothing and empty bottles of her favorite Shalimar perfume. They could be cages. They separate the viewer from content, making it both private and more important to see.

Bourgeois’ mother had to put up with an erring husband. The focus of Bourgeois' lifelong venom was directed at Sadie, her tutor when Bourgeois was ten. This young English woman shared her father's bed. The father was an Anglophile: the English could do no wrong. This let Sadie off the hook for the father but not the daughter. Later in life, photographs suggest that Louis was proud of his daughter and father and daughter got along. Yet the juice of Bourgeois' creativity lay in the painful residue he left, which she would release in her art work.

Women may have come a long way in their participation in sexual acts. Bourgeois reminds us in this exhibit of the pain sometimes inflicted during copulation. One female figure has a prosthetic leg. Another has a bound arm. These figures are black, not the soft pink material Bourgeois often uses for mother and child.

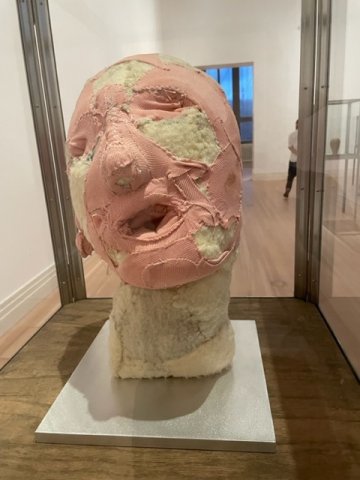

The act of childbirth and motherhood remains unchanged in women’s lives. Powerful pink sculptures of childbirth suggest the pain of the process and also the fear of separation. It is never clear whether the child fears separation for the mother, or the mother fears separation from the child. It goes both ways.

Bourgeois is rightly called a feminist. She focuses on bodies, sex and and feelings. She never joined a movement, led for a longtime by women who did not marry and did not have children. They did not speak to Bourgeois' feelings or to those of most women.

A story often told about Bourgeois has her sitting at a counter in a coffee shop. The young man across from her could not help starting. Perhaps he was trying to place her in his memory. Bourgeois took it in another way. She unbuttoned the front of her blouse, opened both sides wide and said, “Not bad for an old lady.” She was shocking, dirty and twinkling.

Robert Mapplethorpe’s portrait of her at seventy, grasping a rather ugly penis under her arm, is a hoot. She is laughing.

Bourgeois was a ribald, lifeful artist whose work is among the most important of the last century. Her early paintings were recently exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. You can see why Fernand Léger suggested that she turn her attention to sculpture. Using the textiles she knew as a young girl filling in destroyed areas of antique tapestries, she has created heads, bodies and stories of incredible power.