The Scream, Sunflowers, and Mona Lisa

Gone Baby Gone

By: Mark Favermann - Aug 09, 2021

Perhaps we need to call on Sherlock Holmes in order to resolve the 31-year old “no end in sight” Gardner heist?

It happened during the last week in June. Two prominent paintings by 20th-century masters were recovered nearly a decade after they had been stolen from a gallery in Athens. A contractor was arrested for committing what had become a notoriously audacious theft of works by Pablo Picasso and Piet Mondrian.

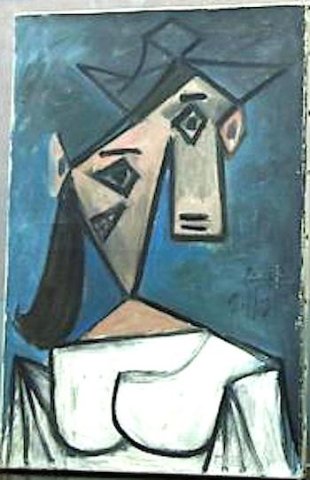

Picasso had gifted his painting to the Greek people to honor their resistance to the Nazis. That work, along with an early Mondrian landscape, was found tucked away in a gorge; the thief admitted having stolen them from the National Gallery of Greece on January 9, 2012. For nine years, Picasso’s Head of a Woman had been hidden in the home of this self-described “art lover,” along with Mondrian’s Stammer Windmill. Their recovery was greeted with celebration in Athens. Unlike Boston’s clown car approach to the still-unsolved Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist, Greece hailed the recovery as a testament to the strength of law enforcement.

In Greece, the incident had been called the “theft of the century.” The nation and the police were shocked by the brazenness of the act, which took less than seven minutes. The paintings were first stripped out of their frames and then taken out of the gallery through a smashed balcony door. The alarm system had been manipulated to send the sole guard on duty scurrying in another direction.

Greek authorities had initially worked on the assumption that an experienced gang was behind the crime. It was a shock that “an art lover,” who simply wanted “to possess the pieces,” was the mastermind. The thief, a 49-year-old divorcé, told the police that he had planned the burglary for six months. Amazingly, he traveled to and from the gallery on the night of the robbery by public transportation.

The robbery occurred at the height of Greece’s economic crisis, and there was a political angle to the analysis of what had gone wrong. The gallery’s poor security system as well as a lack of guards were attributed to austerity measures Athens was forced to implement in return for international loans. It was subsequently learned that the National Gallery’s alarm system and security cameras had not been upgraded for over a decade.

Over the years, there have been several other notable thefts of art masterpieces. These include The Ghent Altarpiece (1934), stolen by the Nazis along with over 100,000 other objects (many were recovered by the Monuments Men). In 2008, four paintings by van Gogh, Monet, Cezanne and Degas were stolen by armed thieves from a private museum in Zurich. The van Gogh and Monet works were recovered. In 2007, Picasso’s Portrait of Suzanne Bloch (worth up to $50 million) and Candido Portinari’s The Coffee Worker (worth about $5.5 million) were taken from the São Paulo Museum of Art in Brazil. They were eventually recovered. In 1991, Sunflowers, van Gogh’s most celebrated work, was among the 20 paintings stolen from the van Gogh Museum, but it was found hours later in an abandoned car.

In February 1994, I was visiting Lillehammer, Norway, to see the Winter Olympics. On opening day, Edvard Munch’s The Scream, the iconic 1893 painting of a waiflike figure in dire distress standing on a bridge, was stolen. It only took 50 seconds. Two thieves broke through a window of Oslo’s National Gallery, cut a wire that held the painting to the wall, and left a note that read “Thousand thanks for the bad security!”

Initially, the theory was that a Norwegian anti-abortion group had lifted the painting. This was proved false after a ransom demand for $1 million arrived. Later, in 1994, this famous Norwegian artwork was recovered undamaged at a hotel in Asgardstrand, about 40 miles south of Oslo.

In 1996, four men were sentenced in connection with the theft. They included Paal Enger, who had been convicted in 1988 of stealing Munch’s The Vampire in Oslo. In 2004, another version of The Scream was stolen, along with the artist’s The Madonna, from the Munch Museum in Oslo. Three men were convicted for that theft in May 2006. Police recovered both works in August, with minor marks and tears.

Besides the Gardner heist, perhaps the most spectacular robbery in the last century or so was of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911. A man, slight of build and with a large mustache, inconspicuously entered the museum’s Salon Carré, where the Mona Lisa was exhibited. Here he hid in a broom closet and waited. Before the museum opened to the public the next morning, he crept from the broom closet clad in a white apron, the standard dress of Louvre employees. He took Leonardo’s oil painting from the wall and carried it to a nearby service stairwell. After removing it from its glass frame, he carefully wrapped the painting in a white sheet, and then made his way to the exit with the picture hidden in the folds of his apron.

Once the museum staff realized that the painting was missing, the police were notified. A museum administrator described the theft in an official statement: “The Mona Lisa is gone. Thus far we haven’t a clue as to who might have committed this crime.”

When the museum reopened a week later, thousands poured through its doors to view the empty space where Leonardo’s masterpiece had once hung. The investigation quickly turned up a high-profile suspect: Guillaume Apollinaire, the French poet. During an interrogation session, he “fingered” another high-profile suspect — Pablo Picasso. Police questioned both in connection with the Mona Lisa theft, but quickly cleared them due to lack of evidence. The investigation hit a temporary dead-end.

Two years later, Alfredo Geri, a prominent Florentine art dealer, received a letter postmarked from Paris. The writer claimed that he was responsible for the theft of the Mona Lisa, and he wished to see the masterpiece returned to Italian soil. Geri contacted Giovanni Poggi, the director of the Uffizi Gallery. The pair invited the man to Florence. Once he delivered the painting, it was immediately sent to the Uffizi. The two promised to meet the thief’s demand, but they were never going to pay the 500,000 Lira ransom. While the picture was at the gallery, it was authenticated and the police were contacted.

The culprit was Vincenzo Peruggia, a former Louvre employee who had assisted with the construction of the glass case that held the Mona Lisa. The police had previously brought him in for questioning about the robbery on two separate occasions. Peruggia was sentenced to one year and 15 days in prison, but he only served seven months. The Mona Lisa was exhibited in the Uffizi Gallery for two weeks before it was returned to the Louvre. (Peruggia was hailed as a national hero by the Italian people!) During the first two days after the painting had been put on view, an estimated 120,000 people visited the museum to check out the “recovered” masterpiece. The sensation generated by the theft no doubt helped secure the work’s archetypal place in the world’s collective consciousness.

In Granada TV’s The Final Problem (1985), Sherlock Holmes (Jeremy Brett) returned to Baker Street after a four-month absence. He had just gone on an important assignment for the French government — to recover the “Mona Lisa,” which had been stolen from the Louvre. He was successful, and the French had rewarded him appropriately. But the detective had provoked the indignation of the mastermind perpetrator of the robbery — the Napoleon of crime, Professor Moriarty. Perhaps we need to field Holmes once again in order to resolve the 31-year-old “no end in sight” Gardner heist.

Posted courtesy of Arts Fuse.