Richard Strauss' Home Town 2021

The Richard Strauss Insitute in Garmisch-Partenkirchen

By: Susan Hall - Aug 19, 2021

Garmisch Partinkirchen is less than two hours by train from Munich, where Richard Strauss was born. After the smashing success of his opera Salome, Strauss hired the Art Nouveau architect Emanuel von Seidl to build a villa on the property located at Zoeppritzstraße 42 in Garmisch.

The landscape here, like the Big Sky in Texas, makes you feel miniscule in relation to nature. Great expanses of blue encourage big thoughts and big feelings. The Tirolian Alps surround the village, their jagged upthrusts framing the Strauss Villa.

The family moved into the house as a summer retreat in 1908 and a little later made the Villa their permanent residence. The two-story building was created by von Seidl with a hipped roof, all the better to withstand strong winds and easy for snow to slip from. The villa is a listed building based on the Monument Protection Act of October 1, 1973. The garden gate is etched with the composer’s initials. On top of an out building, a sculpture of an ostrich sits. (Strauss means ostrich in German).

Strauss composed here, and journeyed from Garmisch to conducting assignments around the world. He died in the villa in 1949, a depressed man. Especially sad for someone who contributed so much to music lovers’ joy. He had come to feel that World War II destroyed the German culture he loved. The opera houses where his works were premiered and then often performed, lay in rubble.

Thanks in part to the popularity of his music, German culture is again flourishing, without the taint of Naziism. A mountain of World War II rubble is covered in green grasses and tall trees in Leopold Park in Munich. So too do the Strauss compositions fill concert and opera halls across the globe.

The Villa’s study contains historical works as well as German classics. The bedrooms on the first floor today house an archive. The room where Strauss died is a memorial.

The house is not open to the public and the Strauss descendants no longer live there. Yet a cook is on staff full time, so that scholars who are working in the archives can eat where the composer did. A motherlode of Strauss correspondence has yet to be released by the family. Strauss fans as well as scholars are eager to find out more about this masterful composer.

The Richard Strauss Institute (RSI) is.a stone’s throw from the town’s main train station. The RSI was set up as a municipal office of the Garmisch-Partenkirchen market administration which also took over the sponsorship. Together with the Bavarian State Ministry for Science and Art, funds are provided for the ongoing operation of the Institute.

In September 1998, the Richard Strauss Institute started provisional operations on a former barracks site, where it remained until it was housed in the Villa Christina . On the 50th anniversary of the composer's death, September 8, 1999, the RSI was reopened in this historic building.

The Institute had just closed when I arrived. I was privileged to have a personal tour and lecture by Dr. Dominik Šedivý, the director. His deep educational background at the premier schools of Vienna, Munich and Salzburg has not dampened his passion and good humor.]

Two rooms on the first floor are devoted to Strauss. In one, biographical material includes a time line, and a special biography for children who can manipulate it like a flight simulator, whirling a wheel. Original scores are on display, and indicate the tight grip Strauss had on his compositions.

In a more personal rooms, a tea service his wife Pauline may have used to distract her husband from his incessant card games and back to the musical drawingboard is on display.

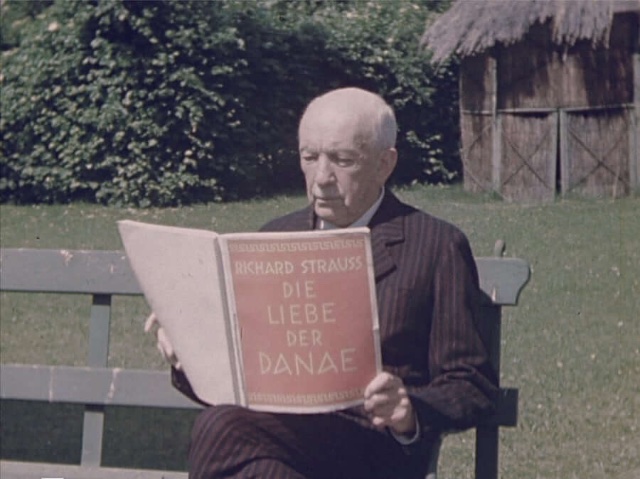

Family footage is looped continuously. Here we not only see Strauss receiving late life awards but also the master sledding with a grandchild in the Villa’s expansive grounds. During the Second World War the boy went to twenty-six different schools. When he was called out by classmates for being half Jewish, and beaten by them, his family sent him to a different school.

A current featured exhibit details the life of conductor Hermann Levi, who also lived in Garmisch. The Institute remembers Levi, detailing his relationship with Richard Wagner, Richard Strauss, Clara and Robert Schumann and others. Correspondence with artists and composers is strung centrally for easy reading at eye level. Performances echo in the room. This is the Strauss Institute’s answer to the movement a decade ago to move Levi’s remains from Garmisch where he died to a Jewish cemetery in Munich. Hermann Levi was conductor of the first Parsifal at Bayreuth. King Ludwig II had overridden Wagner’s objections. Levi was the last man to see Richard Wagner alive.

To celebrate the Hermann Levi weekend from July 2 to 4, Kirill Petrenko, music director of the Berlin Symphony, conducted a program in his honor. Whatever questions arise about Strauss and anti-Semitiism are being answered, step by step as his legacy embraces great Jewish artists. Strauss was not political, he was naive, and was also beloved by his Jewish family and friends.