White Guy On The Bus

Southeastern Premiere of Bruce Graham Play

By: Aaron Krause - Aug 21, 2018

You might hear yourself talk about race when you listen to Molly, a fictional character in a play about the topic.

“Seriously, I mean, you like to think we’re moving beyond all this,” the educator says in White Guy on the Bus. This play is Bruce Graham’s riveting, complex, brutally honest work about this behemoth issue we call race. “I’ll be honest, I think it’s gotten worse.”

But just how ugly have things become?

Simply listen to Graham’s unflinching, disturbingly direct language. It’s peppered throughout the playwright’s exploration of, among several topics, race.

This gripping play is receiving its southeastern premiere in a scorching, well-executed production at GableStage through Sept. 9.

Surely, even those who believe we’ve regressed regarding race will squirm.

For instance, listen to the following dialogue. It's between Shatique, a poor black woman and Ray. He's a wealthy, arrogant white man who works in a shady financial operation.

Shatique: "Black person’s life real cheap to you, isn’t it?"

Ray: "Well, Shatique, if you know anything about economics there is one sure thing: The market always determines the price."

Understandably, Graham has inserted a pause following that remark.

However, in his play about revenge, moral ambiguities, political correctness, image and racial accusations, it’s hard to simply brand folks as good or bad. One reason this is a quality play is that we shift allegiances. Also, Graham offers no easy answers.

Indeed, even the ending suggests the status quo is here to stay.

The play isn’t just a ripped-from-the-headlines drama. Graham isn’t merely intent on debating topical issues so timely you could almost see a mirror on stage reflecting real life.

Rather, White Guy is also a drama with incredibly high individual stakes.

Unquestionably, palpable desperation fills the stage. In addition, we keenly feel a sense of menace in one scene that could feel too melodramatic.

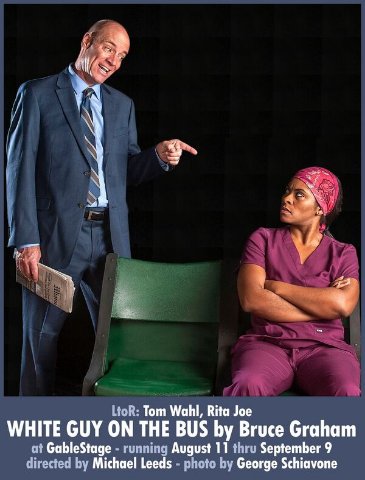

Thanks in part to director Michael Leeds, the immensely talented Rita Joe and Tom Wahl, play the scene to perfection. We shiver after hearing an offer one of the characters makes and the frightened reaction from the other. Sounds of thunder during a rainstorm reinforce the dark ambiance. To say much more would be to ruin the unexpected that Graham has written into his searing, relatable and ultimately tragic piece. It’s must-see theater.

Suffice it to say that nothing prepares you for the gasp-inducing latter part of the play. It sadly illustrates how devastating the consequences can be when someone enters and remains in an unfamiliar racial environment. Unfortunately, this is true even when the person has the best of intensions.

Roz, an upper-class white woman and Ray’s wife, who lives in Philadelphia’s suburbs, could’ve taught at any school. Yet, she chose one in a low-income, black neighborhood where residents are sometimes apathetic and, on at least one occasion, allegedly committed burglary.

Nevertheless, Roz derives satisfaction from educating at-risk youth.

In particular, she’s helping a high school student who cannot read.

But “no good deed…”

“The boy is in “tenth grade (and) can’t read,” she tells Molly, an educator at a practically all-white school, in a well-to-do neighborhood within Philadelphia’s suburbs.

Roz continues: “I keep copies of job applications – not Microsoft or anything, Realistic—fast food places.

Wal-Mart. And we work on – I mean, if he can at least fill out one maybe he can…I don’t know.”

Molly: "You’re…aiming kind of…well, low, aren’t you? With the applications. I mean, it’s as if you’re

saying…okay, you—Burger King. You’re from this neighborhood so don’t expect anything better.”

Roz: "He can’t read, Molly. I can be idealistic or realistic – can’t do both."

Molly: "I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to---"

Such conversations can arise when the topic of race comes up, Graham’s reminding us.

No doubt, some may argue that our journey toward equality in this country has come a long way. But Graham reminds us that we’re taking leaps back. He writes in unusually direct language.

The structure isn’t linear. Instead, it jumps back and forth in time, suggesting, perhaps, that we make some progress on the racial front, but regress shortly thereafter. The play’s title refers to Ray riding a public bus. On it, Shatique heads from her city home to the suburbs, where she works in a hospital and is studying for a degree. Naturally, she’s surprised that someone as wealthy as Ray would take public transportation. His real reason for riding the bus will surely shock audiences.

This bus travels from the city to its suburbs – and back. It’s symbolic, especially for Shatique.

Many might say it’s difficult to envision society, especially with the current administration, from making and keeping a commitment to helping the less fortunate. Even with signs of progress, there will be regressions – just like that bus turning around and heading back to Shatique’s poor, rough neighborhood. There, the predominantly-black residents regularly call the police following unsavory activities. Still, the police never seem to respond. Sound familiar?

In particular, it might seem that Ray’s a character with little redeeming qualities.

To be sure, the versatile Wahl endows him with arrogance. In addition, there’s a sarcastic, jaded aura about him (picture a harsher Bill Murray in the 1993 movie Groundhog Day.) But Wahl also invests Ray with hints of conviviality during certain scenes with Shatique.

Certainly, Wahl’s Ray is a man who obviously loves his wife, during scenes with and without her. He seethes, clenches his teeth in anger and thirst for revenge during appropriate times – not at her, but for a reason that we won’t reveal.

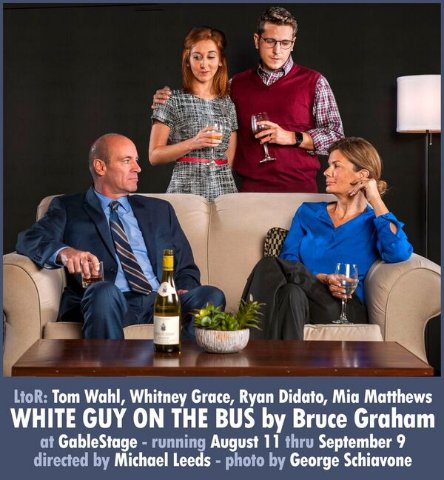

Meanwhile, Mia Matthews doesn’t turn the opinionated Roz into an unlikable woman.

Of course, Matthews’ Roz voices her opinion freely. Still, the actor also conveys charm, elegance and sophistication, without coming across as arrogant.

Roz and Ray’s upscale demeanor contrasts markedly with Shatique’s lower-class lifestyle. The brilliant Rita Joe invests Shatique with a weary, depressed countenance, which also manifests itself in her voice. But Joe also conveys an inner strength and determination to improve her life.

Also, Joe imparts a wariness toward Ray, as well as a frustration and anger that threaten to boil over.

In a more mellow role, Ryan Didato’s Christopher still conveys an inner fire and ambition regarding his character’s desire to complete his research. And Whiney Grace contrasts Matthews’ sophisticated Roz with a naïve, idealistic Molly.

The actors, playing on Lyle Baskin’s wide, single set that reveals three distinct locations, practically speak over each other, in a style reminiscent of Mamet speak. It’s a directorial choice on Leeds’ part that, perhaps, suggests how volatile a subject race is.

The play isn’t exactly realistic. One scene bleeds into another, cinematic style and there's little transition between scenes. For instance, Ray exits the bus without stepping down or waiting for doors to open. He then walks right into his or his friends’ house. If only the diverse people of the world could walk as freely as the characters do in this play, this world would be a lot better, the playwright might be saying.

Ellis Tillman has performed his usual great costume work, creating clothes that convey a character’s life situation. In particular, there’s a noted contrast between Ray’s suit and Shatique’s drab clothes.

Although Graham hasn’t written it into the script, Leeds has wisely chosen to contrast the two individuals’ environment at the beginning and the end. Jeff Quinn’s realistic lighting highlights Ray, then Shatique is in the spotlight. Particularly at the end, this suggests things aren’t about to change anytime soon. But more importantly, it’s a call for us to do something to enact change.

But first, we, as a society, must become calm and cool.

Consider how we like to think we live in a “melting pot.” Roz, on the other hand, sees a negative connotation in that phrase.

“Think about it, literally, what is a melting pot,” she asks rhetorically. “You throw stuff in and, eventually, it overheats. Boils over.”

The southeastern premiere of Bruce Graham’s White Guy on the Bus, at GableStage, continues through Sept. 9 at the company’s venue, 1200 Anastasia Ave., in the east section of the Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables (a Miami suburb). Performance times are at 8 p.m. Thursday-Saturday as well as 2 and 7 p.m. Sunday. For tickets, visit www.gablestage.org or call (305) 445-1119.