Pennie Brantley The Presence of the Past

At Real Eyes Gallery

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 05, 2021

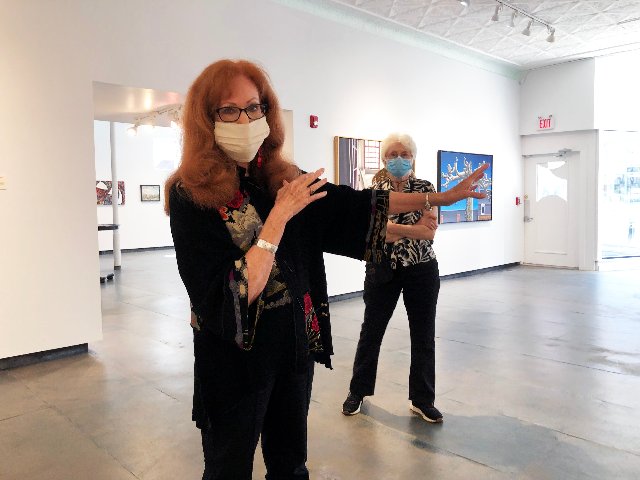

Pennie Brantley

The Presence of the Past

At Real Eyes Gallery

Wednesday, September 1 through Wednesday, September 29

Reception Saturday September 11 from 4-7pm.

Real Eyes Gallery

71 Park St., Adams, MA 01220

Gallery Hours: 12 noon to 7:00 Friday, Saturday, Sunday and by appointment

Phone or text 917-440-2400

For the realist painter, Pennie Brantley, every picture tells a story. Encountering the work in her current exhibition The Presence of the Past there is a lot more to the notion that what you see is what you get.

The viewer will rightly see pristine paintings meticulously rendered. The titles tend to be long and descriptive with some additional text. They invite us to delve deeper into the layers of intentionality.

During an intimate tour some of the discussion had her choking back emotion. That entailed deeply rooted memories of “Daddy” who participated in the invasion of Normandy and connections with a Belgian family. She and her artist husband, Robert Morgan (who showed at Real Eyes in August) have made annual visits to their Belgian friends. They have visited the sites and cemeteries of WWI1 and the Battle of the Bulge which her father participated in.

The pictures also reference as metaphors the many hardships that we all endure.

For Bob and Pennie the Pandemic has meant time in the studio. It also entailed for her the process of recovery from injury to her “painting hand” and surgery from a fall.

The resultant triumphant new work, which she refers to as “My Covid painting,” is a panoramic view that is rightly the centerpiece of a stunning exhibition.

There is a soft play of light bleaching out a palm tree hovering over Moorish architecture. The title is “Indistinct Reflections on the State of the World: Reflecting Pool at the Alcazar de Los Reyes Cristianos, Cordoba, Spain.”

It entailed a push to finish the work in time for the current exhibition. It was indeed a challenging and labor intensive effort.

She explained the demand of painting some 400 plus individual railings. “I don’t use a maul stick she stated.” This is a device used by Old Master painters to serve as a bridge support when painting fine detail.

It’s all done freehand which entails precise control. This is all the more remarkable considering recovering from several surgeries.

“I paint a railing then turn the canvas upside down and have to let the paint dry for several days before completing the other half” she explained. It takes months to execute such fine detail.

Most of the subjects in this show entail rendering of photos she took during their annual trips to Europe. Back in the studio she grids the image and transfers the drawing to canvas. The paint is built up in progressive layers resulting in compelling chiaroscuro.

The works often comprise seemingly impossible challenges as demonstrated by an older work “Morning Fog, Orvieto.” Complex patterns of tile and pavement are rendered in dramatic perspective. In sharp focus they recede in distance with the added dimension of delicate rendering of the impact of fog.

As is often the case with hyper realism it is too easy to take the skill of the artist for granted and respond to the work as decorative, pretty pictures.

This exhibition turns that notion on its head with a stark, even grim series of Holocaust related, social justice paintings. They stem from memories of her father and sacrifices of The Greatest Generation to battle Fascism.

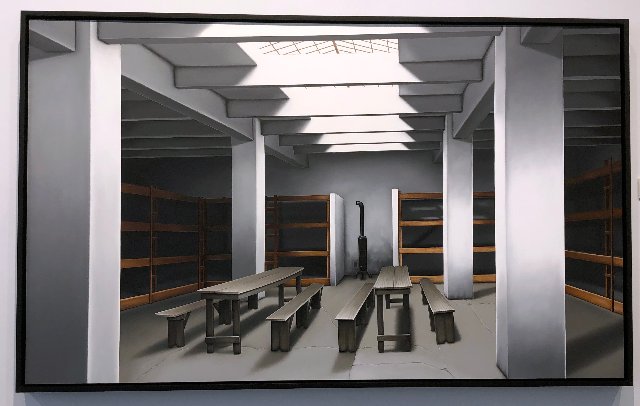

For the first time she is exhibiting a series of works with views of the Theresienstadt ghetto and concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. It was a rural village of some 3,000 with an 18th century fortress. The Nazis forced the first inmates to renovate it as a concentration camp.

At any given time it housed some 40,000 to 50,000 prisoners. Nazi propaganda touted it as a retirement village for the elderly as well as intellectuals, professionals and artists. With a bit of window dressing it was presented as a model camp to the duped visiting Red Cross.

“For the Red Cross visit, even the SS Scharfuhrer [squad leader] Rudolph Haindl was nice to the children for the benefit of the camera . . . he posed for the camera, smiling, and not insisting that he be greeted by Jews from a distance of three steps, as he had demanded just the day before. The town was improved for the purpose of filming and also for the visit by the Danish Red Cross—a request that had been supported by the Swedish government. Jewish women even had to brush the pavement with their hair brushes to help get things ready. The city square, where once there had been only military parades, was transformed into a garden with a musical stage. The city temporarily took on the appearance of a seaside resort. Stores were filled with relatively nice things (not, of course, actually for sale—such things were forbidden for prisoners). For a few days there was even a bank that looked like a real bank. The apartments of prominent Jews were furnished with new furniture. So that nothing would be spoiled the Nazis sent their own people as spies to mingle with Jews on the street, disguised as Jews, complete with yellow stars. Kitchens were painted. All types of cultural events were permitted: opera, concerts and operettas such as Die Fledermaus were performed . . . Nurses were given white uniforms . . .” From Facing History and Ourselves

Conditions were so dreadful that some 30,000 perished of starvation and disease. An estimated 140,000 passed through and were murdered in the death camps.

There are five works on view side-by-side. “I planned to do ten or twelve” Brantley said. “There are still a couple of more images I wanted to add.”

The paintings are stark and minimalist. The hard surfaces of walls and floors, with crude furniture and bunks, take on an abstract quality. Side by side one interior is cool while the other is warm. As adapted spaces they retain skylighting. This makes the views deceptively benign.

The stark plainness of these horrific images recalls the Hannah Arendt phrase “The Banality of Evil.” Brantley describes these interiors as “sanitized.” During their occupation she spoke of the stench of feces, urine and vomit in spaces with no sanitary facilities.

Oddly there was art and music at Theresienstadt given the unique population of the camp. Some years ago there was a riveting exhibition of that work at Mass College of Art. This entailed work supervised by the Nazis as well as secret work which was hidden or smuggled out. It was part of humanistic resistance.

The creation of this series has been harrowing. It’s not the kind of work that easily sells although she hopes that it gets curated into exhibitions and perhaps become acquired by museums.

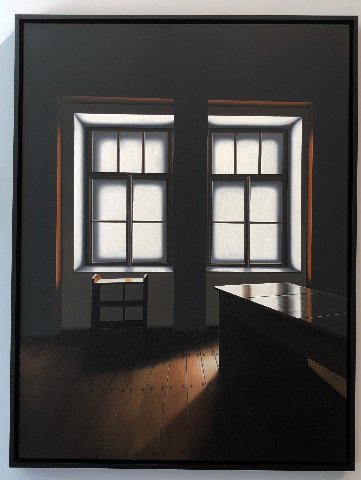

There is a similar intent in “Feeding Vincent: Kitchen of van Gogh’s Asylum: St. Paul-de-Mausole, St. Remy-de-Provence.”

Again we encounter a starkly rendered, minimalist interior with masterful play of light through a curtained window. Without title and text we would assume it to be a study of architecture and interior lighting.

Lovingly it is a place where she focused meditative thoughts of the artist during a time of crisis in a brief and anguished life.

If we take the time to reflect we find that Brantley’s works are often motivated by the deepest empathy. They externalize the struggle of human condition and unbearable suffering.

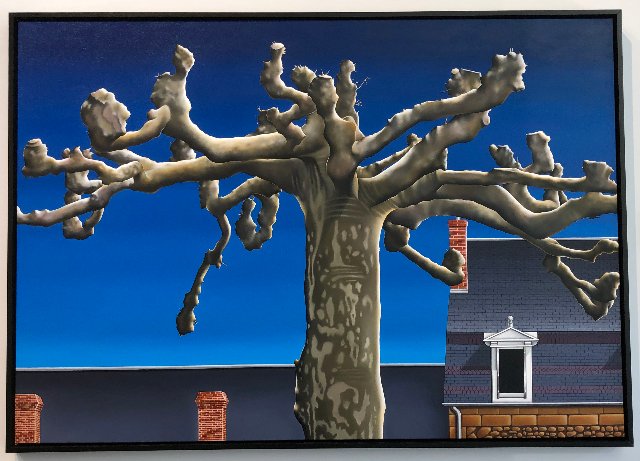

That metaphor is conveyed by the simple and compelling image “Triumph: Sarlat-la-Caveda” of a gnarled tree backed by tops of houses. The pollard trees, so unique to French villages, are severely pruned each year. These causes them to grow back each spring ever stronger.

To paraphrase her comments on this brutal pruning, that which does not kill us makes us strong.