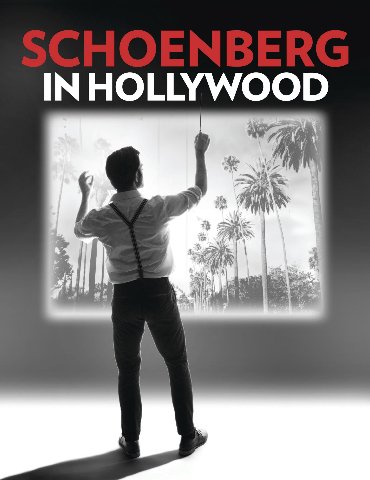

Schoenberg in Hollywood at Boston Lyric Opera

Tod Machover World Premiere

By: Matt Robinson - Sep 14, 2018

Arnold Schoenberg is known as one of the brightest lights of the German expressionist movement and made his marks on canvases and classrooms, scores and stages. Labeled “degenerate” by the Nazis, Schoenberg escaped Austria and Germany to America, where he ended up in California and quickly became one of the most influential artists in the contemporary canon

As a fellow progressive artist, Machover has been hailed for his compositions and also for creating new technologies that allow the boundaries of music to be taken beyond even the atonal heights Schoenberg attained. Having studied with the legendary likes of Elliott Carter and Roger Sessions at The Juilliard School, Machover has headed up talented teams from MIT (where he is Academic Head as well as Director of the Opera of the Future group) to Paris (where he was the first Director of Musical Research at Pierre Boulez’s IRCAM) and has also brought musical expression to larger communities through his famed “robotic” operas and City Symphonies.

Who were your earliest musical inspirations?

I grew up in New York. My mom is a Juilliard-trained pianist who decided to became a very creative music teacher…. My dad was a technologist, a pioneer in the field of computer graphics. So I grew up with both influences in my life. My mom grew up in a European high-culture family in upstate New York, while my dad grew up a pure populist in Iowa, so that contrast influenced me too. I grew up with Bach and Beethoven and really only listened to classical music until I was like 13. But then, when I heard The Beatles, a light bulb went off and I saw how music could be simply expressive and also complex at the same time. A lot of my favorite composers start with “B” – Bach, Beethoven, The Beatles, and the English Renaissance composer William Byrd. I also worked with Boulez for a while. As my parents also had a strong interest in both music and technology, we also listened to a lot of avant-garde music so I grew up with a great mix.

Do you find yourself particularly drawn to Jewish artists?

There is part of the opera where Schoenberg is thinking back on his growing up in Vienna…. He grew up in a very religious family, knowing traditional Hebrew liturgy but also loving Classical Western music. In this section of the opera, the music of Bach mixes with cantorial music - through the “medium” of the cello - as if Schoenberg is trying to decide how they might fit together. I also loved the music of Bach growing up - especially his liturgical music. My mother’s family was pretty observant and I was lucky to grow up listening to some of the best cantors I have ever heard, and they were also great family friends. So I love that music! And especially since I am a cellist (as Schoenberg was) – it is a special instrument because it is exactly size of a human body and it covers the entire range of the human voice – I played Bach and experimented with cantorial music and wired my cello for rock, and morphed all of this in many ways.

When did you first hear Schoenberg and what excited you about him?

My parents were immersed in Classical music but they were also quite adventurous. My mother had been to Juilliard where the Juilliard Quartet had recorded Schoenberg’s music, including his famed String Trio. My mother had also studied with Eduard Steuermann who had been one of Schoenberg’s top students. He had even premiered his Piano Concerto in the 1930s. Schoenberg’s music is difficult, so I did not play it until later, but I did listen to it quite a lot.

I have always admired [Schoenberg’s] music and his being an uncompromising, courageous inventor who was always ahead of his time. He took risks and wrote what he felt had to be expressed. It took the audience a long time to come around and, in many ways, is still not as appreciated as he should be, and that Is part of the reason why I wrote this opera.

About 20 years ago, I came across a book called Arnold Schoenberg: The Composer as Jew by Alexander Ringer. It is an amazing book! I had never really thought about Schoenberg's Judaism. He had written an opera called “Moses and Aron” that he never finished and his other Jewish-themed pieces were not among his most famous. But in reading Ringer's book, I realized how his connections to his Judaism were profound and personal. I also realized how much of the resistance to his music, especially in Europe, was very mixed up with anti-Semitism, even when when critics about harmony (supposedly an “Aryan” quality) and melody (supposedly an “Oriental” or “Semitic” quality). Schoenberg actually wrote one of the very best books on harmony ever - Harmonielehre or Theory of Harmony – I keep it by my composing desk – so he knew harmony better than anyone. But as he deviated from traditional tonal harmony from ca. 1910-1930, people said that he was writing meandering Oriental/Jewish melodies unconstrained by the rules of harmony. Of course this was totally wrong–he had found a new kind of harmony–but learning from Ringer that people talked about Schoenberg’s music in that way made me realize how deeply music is tied to all of our ideas - and prejudices - about politics, religion and identity. I wanted to explore this more deeply, and that is where this opera came from.

Even when Schoenberg converted from Judaism in his teens, he picked the “wrong” religion, becoming Protestant (like Bach) in Catholic Vienna. But little by little, with the rise of anti-semitism and Nazism, he fully discovered his Judaism and realized that many of the sounds, structures and underlying principles of his music were closely related to Jewish music and ideas. So he converted back to Judaism in Paris, soon after Hitler came to power (with Marc Chagall as the witness). I don't know many people who did that- in 1933! And for the rest of his life, he kept searching for what Judaism meant to him. He was asked to be the president of the Jewish State and even wrote a constitution for Israel. He also spent his years of exile in Los Angeles (1934-1951) thinking about how music could make a real difference in the world. So when Schoenberg got to Hollywood-which was about as far as you could get from Europe in those days, he was completely energized to write music that would wake people up to the destruction of Europe and the annihilation of the Jewish people. And I always loved this courageous contradiction in Schoenberg, because his music was the most complex in the world, but - poignantly - he still struggled to try to make it communicate with greatest impact. He wanted to make a difference for the Jewish people and for all people.

In Hollywood, he made friends with all kinds of people who you would not have thought he would have known or liked, including George Gershwin, Charlie Chaplin, and the Marx Brothers. It was Harpo Marx who introduced him to Irving Thalberg, the young Jewish head of MGM, who asked [Schoenberg] to write a film score for “The Good Earth,“ which in fact went on to win the Oscar that year. But Schoenberg priced his services way too high, and asked to control all aspects of the film’s sound - including the pitch contour of the speaking voices - so this collaboration never happened. My opera is about what would have happened if Schoenberg had written that film score, reconciling all of the opposites in his character, and writing his crazy, wonderful music so that it would reach millions and change the world. The idea of Schoenberg meeting Thalberg - another Jew from a totally different background - seemed so odd and funny, poignant and promising and inspiring, that I decided to write an opera about it.

How does his desire to expand musical repertoire relate to your own expansion of musical technologies and your desire to bring music to larger audiences?

I do spend a lot of time thinking about new technologies that expand the palette of the orchestra, the potential of instruments, and the ability of non-musicians to become actively involved in sophisticated music-making. There is a lot of this technology in Schoenberg in Hollywood, but it is meant to help the music and the story, rather than to draw attention to itself. Paradoxically, I often use special amplification and electronics in this opera to make the acoustic instruments sound more magical, blended in unusual ways or floating in space so you can almost touch them. I also use special technology to increase the kind of blending that can happen when melodies, harmonies, timbres and textures of sounds can come together to create something new, like Schoenberg tried to do in reconciling so many different objectives and feelings. In fact, this is what I always try to do with my music in general, and what I have worked especially hard to achieve in this opera. I wanted to create a special musical language that would include all of the musical feelings that I love, and would have ample room to welcome Schoenberg in. In this way, I think I have been able to make a new kind of connection between Schoenberg and Bach and Beethoven and The Beatles and strange new (hopefully beautiful) sound worlds. I wanted this all to feel fluid and natural, and I also wanted audiences to come away loving Schoenberg as much as I do.

How do you make Schoenberg’s story and his music accessible?

Well, the opera moves pretty quickly, and it is quirky and surprising and fun, sen crazy, but I think audiences will easily be able to follow everything, words and music both. One thing that was important was to keep Schoenberg himself at the absolute center of things, no matter what else is happening. I originally thought of the hundreds of amazing characters Schoenberg knew in Europe and in Hollywood, but the more I worked on the project, the more I realized that audiences had to care for Schoenberg as a character and an artist and a person, and I think that will be something people will feel. He is there from beginning to end and you are always experiencing everything with him, through him. In fact, there are only three singers in the show – Schoenberg himself, and what are called in the libretto “A Boy” and “A Girl.” These two start out as Schoenberg's students. (In fact, Schoenberg was one of the world’s greatest teachers and, despite the fact that he composed this complicated music, he really knew how to explain it). These two young singers take on very many different roles, including Schoenberg's two wives and the Marx Brothers. Having things focused around just three singers keeps the opera grounded and the progression extremely clear. As for the music itself, it is extremely varied and - I think - quite fun to listen to. The opera is full of melodies - some of which I hope audiences will go away singing - as well as lots of interesting and intriguing sounds. When things get a little tricky or sly, it always snaps back. Of course, it is up to the audience to see if this all works or not. I know that I truly enjoyed working on Schoenberg in Hollywood, and hope that audiences get as much pleasure and stimulation out of listening to the opera as I did in writing it!

From November 14-18, Boston Lyric Opera (www.blo.org) will bring Schoenberg back east with the world-premiere production of Tod Machover’s “Schoenberg in Hollywood.”

Courtesy of (www.thejewishjournal.org)