Toronto International Film Festival 2010

Ten Days of Cinematic Immersion and Revelation

By: Mark Favermann - Sep 17, 2010

Like the sparrows returning to Capistrano each year, the week-end following Labor Day marks the annual return of the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). The 10 day megafestival is arguably the largest film festival in the world with the most films, diverse categories and largest audiences. This year it runs from September 9 through September 19.

In recent years, the buzz for major and minor films has translated into box office receipts, international acclaim and Academy Awards. However, most presentations are not circulated much beyond this festival. The film business is fickled. Many filmmakers try, but few films are chosen. Seven films show the diversity and range of the TIFF offerings. These include examples of the good, the bad and the ugly. One has the breakout film of the year written all over it. The others represent the variety of the film festival.

Starting on Friday night was the world premiere of the film Marimbas From Hell. Any movie with a name like that and from a place like Guatemala promises cinematic excitement or at least potential. The marimba is said to be the national instrument of Guatemala. It is unclear whether or not there are national instruments of many nations. The bagpipes in Scotland? Perhaps, the French Horn in France?

Unfortunately, this film was no better than a graduate student’s attempt at a quasi-documentary revolving around three strange men who were disconnected from their own realities. Don Alfonso Tunche is a classical marimba musician who seemed to be suffering from much of his region's and thus his world’s problems. His steady gig at a restaurant that served foreign tourists no longer felt that his music was appreciated. He was pink-slipped. Claiming that a gang was trying to blackmail him and threatening his family as well as his beloved marimba, he needed to abandon his apartment and find a hiding place for his marimba. Too many shots were shown in the film of Don Alfonso pushing his awkward marimba in the streets and on sidewalks to find an appropriate hiding place. He also comb his hair an awful lot.

He contacted his godson, Chiluilin (played by Victor Hugo Monterroso) a physically deformed and odd acting young man who seems to live an underground and rather nothing important or even worthwhile existence. He just sort of survives. Eventually, Chiluilin pawns Dom Alfonso’s beloved marimba for money for a young woman. They snort (huff) what appears to be glue and seem to have sex. Don Alfonso is furious when he discovers his beloved marimba is missing. Chiluilin seems unfazed. Perhaps, this is because he finally got laid. Who knows? Who cares?

The third character is Blaco (Roberto Gonzalez), a heavy metal, long-haired scruffy, unappealing MD, yes medical doctor. Blaco’s looks repulse patients, gets him in fist fights, but he is the repository for all things rock and roll. The idea is suggested that Don Alfonso play in the Doc Blaco band. So bizarre is this concept that Blaco thinks it is cool. Though promised and practiced, it never really happens. With the possible exception of a few interesting screen shots in the Guatemalan urban slums, the storyline seems to go nowhere as do the characterizations. The point seems to be that working out of the box, against the norm, is not the way in Guatemala. Directed and written by Julio Hernandez Cordon, this rather bad film like Don Alfonso’s marimba playing seems tinny and way off-key.

Biutiful is the story of a man in literal free fall. The auteur director Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu has created a man in search of redemption continually stymied by darker and darker events. Biutiful is Gonzalez Inarritu’s first film in his native Spanish since his landmark debut of Amores Perros. Academy Award winner Javier Bardem (No Country for Old Men) is the tragic hero. Bardem won the Best Actor award for this strong role at the most recent Cannes Film Festival.

Somehow connected to the afterlife, Uxbal (Bardem) is a son, father and lover living in the underside of the usually beautiful city of Barcelona. This film is shot from the perspective of the anus of the city rather than from its usually exquisite crown perspective. Barcelona's environment is as dark and shady as Uxbal's work. He is a shifty, underground businessman that traffics in illegal immigrant Chinese labor deals and illegal African street vendors. Counter to his wishes, the Africans more than dabble in drugs.

His previous line of work was as a drug dealer, an occupation that haunts him and leaves him full of guilt. His strange bipolar wife works as a prostitute. After peeing blood and visiting a rather unsympathetic doctor, things get even worse when he discovers that he has a short time to live. Embedded in the narrative are human elements of the illegal immigrants themselves, the sometimes cynical clients for his afterlife interpretations, police corruption and dark and dangerous twists and turns. Did I say that Barcelona has never looked worse? Yet, there is a certain elegant craft in the film: its cinematography and its editing are superb. This is not an easy film to watch. Death, dying and barely living are shown brutally in a journey down a most difficult path of human existence.

There is always a film with great “buzz” at TIFF. Last year, it was Precious; the year before, it was Slumdog Millionaire. This buzz is the early indicator of Academy Award potential. This year the buzz was around The King’s Speech. The story could have been painful and tedious, but somehow has been given life, emotion and tension that underscores a very human quality in an unusual and quite unexpected way. This film has quality all about it. From a brilliant, star-studded cast to a measured and elegant visual and verbal rhythm, it is a true story that has not been previously shared.

The film is about the Duke of York, the second in line to the throne of England, who has a terrible stutter that makes his public life and public pronouncements excruciatingly difficult. He has embarrassed himself and the Royal Family for decades when asked to speak in public. His father, King George V, and his older brother, the Prince of Wales, intimidate and make fun of him. The radio has changed the public landscape. By the mid 1930s, the voice of the monarchy can be heard. And as King George V (Michael Gambon) comments,” members of the royal family are forced to become the lowest of creatures: actors.” However, his son Bertie (Firth) has a stammer that makes him to be considered unfit to be king.

The narrative could have been rather difficult and unappealing. Instead the story is told with extreme grace and acted with subtle nuance by Colin Firth as the man who became George VI, the father of Queen Elizabeth II. This star turn puts him in line for an Academy Award. Firth's body of work is there. Geoffrey Rush is also gold-plated in his performance as the new King’s unorthodox Australian-born speech therapist named Lionel Logue. A best supporting Oscar could certainly be expected. Helen Bonham-Carter plays a feisty (what else?) Elizabeth, the future Queen Mum, who encourages the reluctant Bertie to work with Logue.

When his older brother, King Edward VIII (Guy Pearce) abdicates the throne, Bertie becomes the king and must assert the authority and courage to lead his country into war. Through Logue’s unconventional teaching methods and his own heroic efforts, Bertie eventually learns to control his stutter. It is an elegant period piece in the best sense depicting a time and place in its historical and visual context. This is a strange, yet uplifting story the shows a powerful man who due to his speech impediment feels rather frustratingly powerless. The relationship between Bertie and Lionel allows the new king to break through and embrace his own personality and personal courage.

The King's Speech is one of those must see movies. Great performances are received from each accomplished cast member. This is particularly true of the performances of Firth and Rush. Their onscreen relationship that is at once combative, respectful, encouraging and even tender forms an unusual friendship that is central to the movie. It is a wonderful cinematic experience and says Oscar all over it.

Matariki is a New Zealand film trying to do too much with too little. Or is it too little with too much? Writer/director Michael Bennett’s first feature film has five intersecting stories that supposedly merge into a portrait of community. This is a community barely succeeding at the lowest levels of functionality. Symbolism abounds with the stars of the Pleiades Constellation coming together to mark Matariki, the Maori New Year, a time of new beginnings.

The film begins with a house breakin by Aleki, a teenage Maori from a distant, isolated small island in the South Pacific. Played by Jason Wu. Aleki is caught between his father’s traditional values and the temptations of the diverse cultures of South Auckland, NZ. Aleki is also an expert car thief. All the white people in this film or either cops or robbers, drug addics and ex-cons. The Maoris portrayed are more a cross-section of the population, including the good and the bad. This film is a mess. With the exception of an emotional Maori extended family bereavement ceremony, nothing else much mattered or seemed meaningful. Few of the characters were likeable or memorable. The hope and transcendence that the director was striving for seemed weak and unclear. This is a film not so much about transformation but misdirection and discomfort. This was the ugly side of New Zealand. Because it is by a rare Maori director, perhaps it will play at several other film festivals.

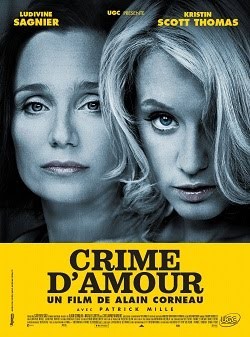

Mixing business and pleasure can be dangerous. This is the premise of Alain Corneau’s French thriller Love Crime. Power plays, one-upmanship and seduction in the rarified air of multinational agro-industry giant executive suites. Starring the polished Kristin Scott Thomas and the evolving Ludivine Sagnier, the plot pits Christine, an office managing director from hell, played by Scott Thomas against her young associate director. The Paris office is a playing field for mind games and psychological and emotional manipulation of the younger woman. Isabelle (Sangnier) falls under her director’s charms allowing her to take credit for her own brilliant ideas and work.

To placate Isabelle’s resentment, Christine allows and actually encourages her to have an affair with her own lover, Philippe (Patrick Mille), who is the company’s accountant. Philippe has been discovered by Christine taking funds from the company. She blackmails him.

In the ebb and flow of power, intrigue and passion, there is at stake a promotion to the head office in New York for either Christine or Isabelle. The tension between the older woman and the younger woman is laced with sadomasochism. Public humiliation of the younger woman and nasty office politics eventually lead to the murder of Christine. Isabelle is the prime and only suspect. She is incarcerated and slowly through flashbacks is able to extricate herself from the murder charges.

It becomes evident that Isabelle is a master even champion manipulator herself. Christine appears to be just a mere amateur next to her. Yet, the story is far-fetched, the love affair is rather unconvincing and the ending is too expected. This starts out film noir and ends more CIS. This film is fun but not very realistic.

The sets are minimalist and elegantly abstract. The Pharoah Sanders saxophone score is fabulous. Certainly, because of its style and cast, many people will go to see this movie but it has gaps and spaces. It is a good entertainment but not a great film. Sadly, Director Alain Corneau died in August two weeks after completing the film.

Made in Dagenham is a formulaic film based upon the 1968 true story of the female workers strike at the Dagenham Ford Factory outside London in protest of sexual discrimination in regard worker skill recognition and wages. Rita O’Grady led nearly two hundred women to protest working conditions, hours and lower wages. The final straw was when the Ford Motor Company decided to classify the women as unskilled workers. This galvanized the women into advocates for equal pay.

Director Nigel Cole (Calendar Girls) who is considered to have a populist touch has dramatized this event in British labor history into a feel good narrative about working class people who happened to be women. Sally Hawkins believably plays Rita as an evolving labor union leader who finds her voice and therefore can speak for others. Their sympathetic union rep, Albert Passingham, played by Bob Hoskins fosters the women’s mission and sense of justice.

Documentary footage of the Dagenham factory and the period that the strike took place underscore the dramatization. Eventually, Rita and her colleagues meet with the Minister of Labor, Barbara Castle and the strike is resolved. Along the way, Rita and the women are met by male prejudice at every level-from their own union, the other workers and even their husbands/boyfriends, Ford’s reluctance to give in and even governmental inertia by the then Labour Government. This is Davida against Goliath. The women of Dagenham win the battle in the end, but eventually British industry loses the war. This is the beginning of the deindustrialization of Great Britain. This is a film with a bittersweet ending.

If you take two aspects of entertainment and mix them together, sports, i.e., ice hockey, and musical comedy would probably not be two of them. Yet, writer/director Torontonian Michael McGowan has done just that with Score: A Hockey Musical. To call this film so Canadian would be an understatement. It stars a newcomer, Noah Reid as a home schooled, sheltered 17 year old hockey phenom, Farley, who is the second coming of Wayne Gretzky or Sidney Crosby (two earlier teenage stars who went on to become National Hockey League and Canadian greats). When the kid joins a junior team, he achieves instant stardom becoming the darling of the media. Score opened this year’s Toronto Film Festival. How Canadian to have a hockey film inaugurate TIFF 2010!

As the overprotective mother and father, wonderful and still appealing as a blonde earth mother Olivier Newton-John and singer/songwriter Marc Jordan add to the musical. Slightly more than cameo appearances from singer Nelly Furtado, Canadian talk show host George Stroumboulopoulos and others add to the texture of the film.

Though few of the songs are memorable, there is a lot of energy in the film. The conflict in the film is not in the story but the attempting to balance the absurd with the serious, the ridiculous with the National sport. Filmmaker McGowan attempted to broaden the film’s appeal, but failed in his all things for everybody approach. Though the film may be too Canadian for a more international appeal, there is a lot of good in the film as well. It is entertaining while not being too challenging, cartoonish without being totally buffoonish, and it is eccentric without being freakish. However, Score is no Slapshot (1977), the classic hockey comedy film with the late Paul Newman.

The hockey maybe basic, but the notion is layered. This is about a national obsession that is both nuanced and communally shared brought to life by music and choreography on ice. Purists may not like it, but it is still entertaining. Score: A Hockey Musical may be better as a Broadway show than a film. A little tweaking of the music may get the puck in the net. In some ways, this film was so bad that it was actually good.

The Toronto International Film Festival is a cinematic feast. There are a soupcon of documentaries, children's films and animations as well. Not everything tastes good, but what does is simply delicious. It is a yearly ten day opportunity to sample and savor the world’s cinema.