Philip Guston Now to Not Now

What He Meant to Boston’s Artists

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 26, 2020

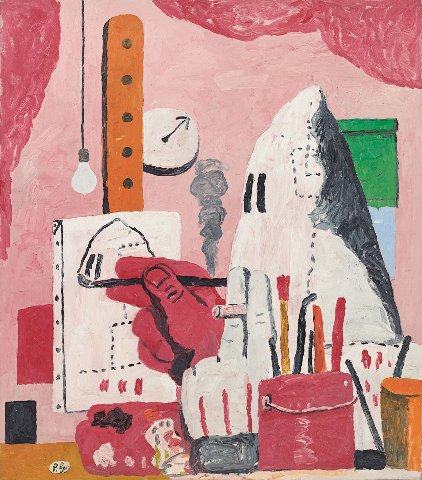

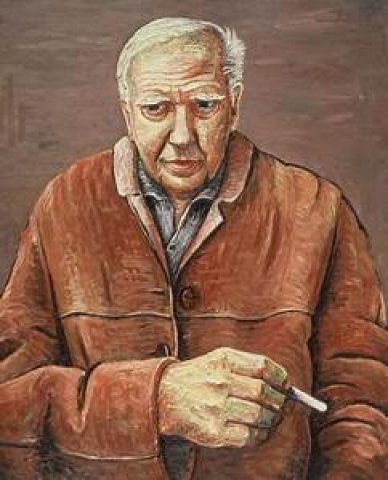

In the 1970s, reacting to the Vietnam War, Philip Guston (1913-1980) abandoned abstract expressionism and adapted a cartoonish style that initiated the movement of neo expressionism.

There was a raw brutality to the intentional primitivism of the paintings. They focused on the mundane including many portraits of shoes. One might compare them to those of Vincent van Gogh. Other themes were clocks, bare lightbulbs, cigarettes in ash trays and cherries. The palette was limited to smoky grays with accents of acidic red. Regarding color the Guston paintings were notable for what they limited. That was a consistent rollover from his abstract paintings.

The works were charged with unique expressions of agita. His sense of despair with the world at war also turned inward. There are many takes on his bad habit of smoking. Likely he was aware of the related health issues that led to a fatal heart attack.

Born in Montreal he was an intuitive artist who began painting in 1927 at the age of 14. He enrolled in the Los Angeles Manual Arts High School. Both he and Jackson Pollock studied under Frederick John de St. Vrain Schwankovsky. During high school, Guston and Pollock published a paper opposing the high school's emphasis on sports over art. Their criticism led to both being expelled, but Pollock eventually returned and graduated.

From an early age in LA he was aware of the Ku Klux Klan’s persecution of Jews. In 1923, perhaps caused by that American pogrom, his Ukranian born father (Goldstein) hung himself in the family shed. Philip discovered the body.

Digging deep into his heritage and psyche paintings focused on the theme of the Klan emerged in the work.

When first exhibited this shift from abstraction resulted in scathing reviews by Hilton Kramer in the New York Times and Robert Hughes in Time Magazine. Kramer, who was often a pompous ass and bigoted jerk, stated that Guston was "A Mandarin Pretending to Be a Stumblebum." While shunned by his peers, uniquely, the bold new direction was understood and encouraged by Willem de Kooning.

Marlborough Gallery, which represented him, did not renew the contract when it ran out. The artist endured a trashing and retreated to Woodstock, New York. He soon joined the David McKee Gallery which represented him until it closed.

Significantly, the port in the storm proved to be Boston. From 1973 to 1978 he taught a monthly graduate seminar at the Boston University School of Fine Arts. The head of the school was David Aronson, a second-generation Boston Expressionist. Widely regarded as conservative and academic, the school was notable for its focus on figuration and representation. Guston was a perfect fit in moving this base in a more dramatic, experimental direction.

His visits to Boston were regarded as major events. He had a particular champion in the poet Bill Corbett who wrote about the artist for Art New England. He published “Philip Guston’s Late Work: A Memoir.”

That five-year stint revitalized the singular movement of Boston Expressionism that was launched by Jack Levine, Hyman Bloom and Karl Zerbe in the 1930s. Zerbe taught at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. With the presence of Guston recharging the battery a generation of neo expressionists was launched. Closest to the source was Jon Imber who created compelling portraits of the master.

Given the depth of his Boston legacy it is no surprise that the Museum of Fine Arts was one of four venues for the soon to be launched, now postponed, retrospective “Philip Guston Now” which has been rescheduled for 2024.

As the New York Times has reported “The Guston retrospective, the first in more than 15 years, was supposed to open in June at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. It would then move to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, then to Tate Modern in London, and finally, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“Titled ‘Philip Guston Now,’ it contained 24 images with imagery that evokes the Klan, a spokeswoman for the National Gallery said, and two more where the imagery is less obvious. In total, there would be a selection of roughly 125 paintings and 70 drawings, though the final selection would have been different at each museum because of budgetary concerns and logistics.”

The article conveys the deeply divided responses of museum trustees supporting the postponement, prominent curators denouncing it, and agitated artists. The museums demurred that in the prevailing zeitgeist they needed more time to “contextualize” a hot potato exhibition.

Critics, however, protest that the ground breaking Klan paintings represented the artist’s frontal attack on systemic racism in America. Which he had personally been exposed to as a child.

The craven response of the MFA, however, continues the museum’s long standing ambivalence to the artist.

Ken Moffett was appointed curator of contemporary art by the MFA in 1972. That overlapped with Guston’s teaching at BU. The artist embraced the city which had warmly welcomed him. He offered a painting, the pick of the studio, to the curator known for his commitment to formalism and abstract art.

Responding to the offer, Moffett was not interested in the current work but asked for a painting from his abstract expressionist work. We may assume that the artist regarded that as a snub and insult.

In 1960, at the peak of his activity as an abstractionist, Guston said, "There is something ridiculous and miserly in the myth we inherit from abstract art. That painting is autonomous, pure and for itself, therefore we habitually analyze its ingredients and define its limits. But painting is 'impure'. It is the adjustment of 'impurities' which forces its continuity. We are image-makers and image-ridden.”

The museum did eventually get a Guston by which time his importance was well established. In May 2013, Christie's set an auction record for the artist’s work “To Fellini,” 1913-1980, sold for $25.8 million.

“The Deluge” from 1969, a transitional work in his new direction, was given to the museum in 1992. It was a gift from the estate through his widow Musa Guston. The first of five Guston prints was given to the museum by Elizabeth and Alan Green in 1982. The most recent print acquisition was 2009.

It is well known that the museum’s department of prints and drawings, in the field of modern and contemporary art, has been more progressive than the departments of contemporary art and paintings.

It is arch and vile for these four museums to equivocate on Guston’s intentionality of social justice. That approach threads through the work before and after his status as a first generation abstract expressionist. He was a social realist during the Depression era when he painted murals for the WPA. The easel paintings from that period are more strident than the public, commissioned murals.

In 1934, Guston, artist Reuben Kadish, and poet Jules Langsner visited Mexico. They were given a 1,000-square-foot wall in the former summer palace of the Emperor Maximilian. They produced The Struggle Against Terror, an antifascist mural influenced by the work of David Siqueiros. In a review of the work the artist described them, as "the most promising painters in either the US or Mexico".

When in New York the young Jackson Pollock worked in the studio of Siqueiros. The Mexican muralists were an influence on abstract expressionism particularly the scale of work. Clement Greenberg described that as “the end of easel paintings.” Guston also befriended Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

In the 1970s, Guston was returning to his roots. Museums, particularly the MFA, which has been responding to charges of racism, should know better in presenting Guston’s seminal work.

As former MFA contemporary curator, Amy Lighthill, stated in an e mail “So, how far has the BMFA come?”

Apparently, not far enough. Under director, Matthew Teitelbaum, the MFA has a way to go before it earns street cred. Yet again the MFA had an opportunity to make a statement and blew it.