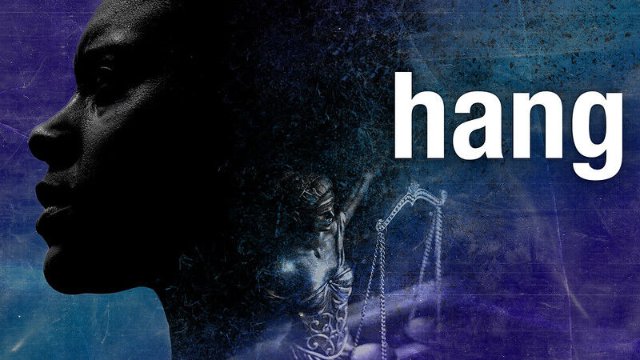

Hang at Shakespere & Company

By Debbie Tucker Green

By: Sarah Sutro - Oct 03, 2021

Hang

By Debbie Tucker Green

Directed by Regge Life

Shakespeare & Co.

Through October 3

A trio of characters enters the office stage setting where Hang takes place. Above them, on a sidewalk people are seen from knees down, on an ordinary day. Just before, a recording of what sounds like a violent mob protesting fills the audio stage. The sound is filled with throbbing life and energy – though we don’t know why.

For aeons of theater-time, we still don’t know what is happening, why these sounds, this ordinary foot traffic, this situation. On the set two government functionaries emerge, a man and a woman in dark blue suits, and a black woman wearing a raincoat, her hair pinned up in a bun. From the beginning, the black woman is the humane character. Her movement is natural, her face expressive, while the other two seem to be caught in some sort of protocol.

Then the banter of do you want a cup of tea, of coffee, or water? The bureaucrats want to “make her comfortable,” and although she refuses everything, they keep offering. The three circle the ordinary rectangular table (picked up at IKEA, the bureaucrats tell her) and finally settle in chairs, ‘One’ and ‘Two’ across from the woman, ‘Three,’ who is being interrogated. They spout random conversation and seem to know her ‘case.’ She and her family have been victims of some obscure crime, though we are far from understanding what her situation really is. The word excruciating is thrown around several times with exaggerated intent about various life situations. There is a sense that the word will become more potent and relevant as the play unfolds.

The two bureaucrats, played by Ken Cheeseman and Kristin Wold, make reference to their ‘training,’ which the woman seizes on and throws back at them, asking how they learned to make her comfortable (which she denies she is) and who played who in the mock role-playing they describe, and did they play her children, who have been traumatized by whatever this interrogation is about?

90 minutes is a long time to be subjected to the controlled and brilliant banter these three take part in, where statements are interrupted before they reach their actual subject and answers and questions are repeated back and forth like an endless badminton game…..all to keep us in the dark and frustrate our innate need to be included in the subtext of this drama. At one point I thought of the large clock at the right center side of the old movie theater in the town where I grew up. No matter where you were in the movie, which was projected on the curtained stage surrounded by complicated curlicued gold leaf decoration, you could always tell the time and know how long the film would be: as a child that gave comfort. But as viewers of Hang we are not given that sense of comfort, of knowing when we will be out of this endless bantering infinite nothingness of dialogue, and have the play’s themes revealed.

Eventually, out of this purgatory it becomes clear that the bureaucrats have asked the woman to come in because of a ‘development.’ She is to make a choice about the punishment for the crime committed, supposedly be given justice, despite the fact it is clear they are not attending to her needs. Language reveals the sterility of the system she is trapped in. The incarcerated man is a ‘client;’ she has ‘choices’ to make; they are all ‘uncomfortable’ with the situation – the language gets more and more ironic and 1984-ish as the action of the play progresses.

And action means these three actors contort themselves into their roles: the bureaucrats in their vertical suits move themselves around the set but manage to remain stiff, even as their affairs, alliances, and traitorous silences take them to the various parts of the room (defined by a water cooler, the table and a shelf of cups and teas). In contrast, Cloteal L. Horne, as the woman wronged, ‘Three,’ is warmly involved. She dramatically leaps to her feet, hunches over the table, strides from one corner of the room to the other as she re-experiences the trauma of her life since the nameless act. With expert awareness and necessary wile, she turns the tables on the bureaucrats again and again, becoming more of the interrogator than the interrogatee, asking them questions they have asked her and mirroring their mechanical answers, taking some pleasure as if this itself were revenge for the crime perpetrated on her, while accruing power.

Much of the play is a study of this language and behavior – which we come to recognize as fascistic. Other elements of the situation emerge, like the perpetrator of the crime- she remembers his blue eyes (is this based on S. Africa’s P.W. Botha before apartheid ended, or another dictator?), referring to ‘him’ as if he is a figure everyone knows, and perhaps some larger societal crime referred to.

In the penultimate scene the man (‘Two’) becomes a salesman. His actions and characterization are perfectly tuned as he enumerates the woman’s choices. She has come into the play already knowing her decision; much is made of this at the beginning despite the fact the others keep offering her new information. A letter is revealed from the criminal, and she tries to get One and Two to describe it to her, despite their protestations of not being ‘allowed’ to share what they have read…she must read it herself. In some of the finest acting in the show, Ken Cheeseman diabolically lists the ways the criminal can die: the various benefits of injection, gas, …while the woman feeds him his lines, adding beheading? firing squad? hanging? – though all these seem defunct means. At each suggestion he artfully concocts reasons why each is a viable choice in florid sales language that exhibits the height of ridiculousness and heartless insensitivity. She eggs him on, perhaps because she has already made her decision: ‘HANG.’ Despite her circumstances she holds the upper hand.

In the end the two functionaries leave the room so that ‘Three’ can read the letter herself, and as the lights fade we see another office, above, where One and Two are laying down the papers she has signed on a filing cabinet and moving on to their next - for them - dry assignment.

In the playbill the setting is described as ‘Nearly now.’ How prescient the playwright is, to recognize old and new layers of fascism, terribly becoming everyday.