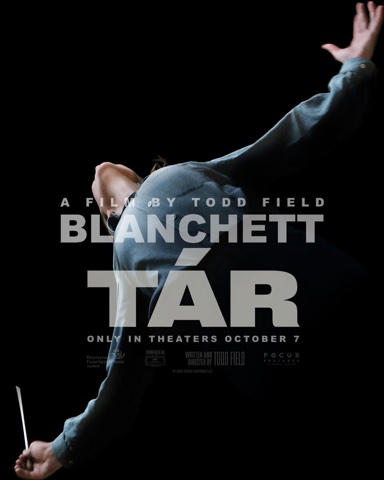

Cate Blanchett Becomes an Orchestra Conductor

Todd Field's Film Opens New York Film Festival

By: Susan Hall - Oct 03, 2022

Cate Blanchett is an orchestra conductor Lydia Tár in Todd Field’s new film Tár, which premiered at the New York Film Festival. Anyone who has been exposed to Blanchett’s performance will be eager to see her latest, mind-blowing work. This is also an opportunity for the unexposed to be introduced. Blanchett is an actress who will always take a dare and push herself beyond perceived limits.

For those of us who follow Blanchett, we can see some of her relationship with Rooney Mara in Carol. Yes, she is gay and shares a child with Sharon (Nina Hoss). the first violinist of the Berlin Philharmonic, of which Tár is chief conductor.

This theme has a long history in the real world of conductors. No one criticized Dimitri Metropoulis who paved the wave for the beautiful young Leonard Bernstein, or of Bernstein who did the same for Michael Tilson Thomas, only referred to as MTT in Tár. James Levine is referred to as Jimmy. His tragic story rests in large measure on the current, jealous General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera and its Board of directors. Tár’s story also ends badly, but the fault lies squarely on the conductor. The richness of this storyline is not explored in the film.

The Berlin Philhamronic is the leading orchestra in the real world. The Dresden Orchestra plays them in the film. They are housed in the iconic Berlin Philharmonie, the first of the vineyard seating venues, built from 1960-1963. In the US we first saw this form in Frank Gehry’s Disney Hall in Los Angeles forty years later. You don’t get the feeling that the chief conductor of the Berlin orchestra has to be as talented as Joe Torre or Aaron Boone, getting a team of super stars to play together.

The film is about the perils of power for all comers, and especially women. The character Lydia does have music in her soul, and her passion is based on a gift she was given. We meet her when she has arrived. Her back story is revealed only at the end of the film.

Blanchett worked with Natalie Murray Beale on conducting. Beale like Blanchett was born in Australia. Murray Beale studied at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music with Post Graduate training at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. Murray Beale is a Professor at the Royal College of Music and formally, and creative director of Independent Opera at Sadler’s Wells.

Members of the Berlin Philharmonic vote on their conductor. Yet you don’t sense at any point in the film that the orchestra has picked Lydia. She is a very good conductor, although her gestures suggest C list women conductors without innate musicianship. Gifted conductors like Barbara Hannigan, Susanna Mälkki and Yi-Chen Lin don’t do histrionics. Jagged, dramatic wild movements of the hands and arms may feel like passion to a conductor. They are not heard as passion by a listener. Over energetic gestures are no substitute for musicality.

Tár speaks about being lonely, but not the way conductor Riccardo Muti does Muti and the current Berlin chief conductor Kirll Petrenko spend much time alone studying the score. The very nature of their work makes them lonely. Studying a score might be very boring on film. Yet Tár's constant movement from one situation to another, with people around all the time, does not suggest loneliness. She only sits alone when she is in her first Berlin apartment and composes a line of five notes. (A new love interest, a Russian cellist, suggests she changes a note to B flat. Tár scribbles on the score: For Petra, not Sharon with whom she shares a life).

Little insider references add pleasure. Luchino Viconit is mentioned. Mahler’s Fifth is the symphony Tár is recording for Deutsche Grammophon. No music in film is more iconic than the Adagietto from the Mahler Fifth in “Death in Venice.” Tár/Blanchett talks about Bernstein playing the Adagietto at Robert Kennedy's funeral, taking 13 minutes. She takes 7. Now that’s a conductor talking about her work rooted in time. Her young daughter toys with her metronome. Tár has difficulty containing her anger at this impermissible entry into her private space.

It is to director Todd Field’s and Blanchett’s credit that you can't take your eyes off the screen for over two hours (speaking of time). In the end, the film feels like pieces patched together. Blanchett keeps it whole, but individual scenes are disconnected: A wonderful interview by Adam Gopnik of the New Yorker as Blanchett’s book is being published. A scene at Julliard in which a woke violinist/conductor trashes Bach. Blanchett’s defense of her daughter against a tiny bully. Each is a gem.

In the end, we don't feel the music, which may not be important for an audience unfamiliar with this world.