A Streetcar Named Desire

Tennessee Williams in South Florida

By: Aaron Krause - Oct 14, 2019

Brutal reality shatters sensitivity, fragility and illusion with the force of a monster hurricane in the professional, nonprofit Palm Beach Dramaworks’ highly intense, heartfelt and heartbreaking production of A Streetcar Named Desire.

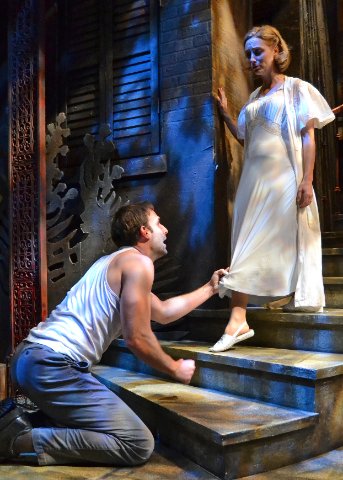

To be sure, in this first-rate mounting of Tennessee Williams’ Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, Stanley Kowalski (an excellent Danny Gavigan) has feelings. Indeed, the actor ensures that the character doesn’t seem like an unfeeling brute. In fact, he has very human feelings.

But make no mistake. Gavigan imbues Stanley with a frighteningly explosive sharp edge. It slices through Blanche DuBois’ fragile, sensitive aura and illusory world until she’s essentially reduced to Humpty Dumpty.

In Dramaworks’ Carbonell Award-worthy production, onstage through Nov. 3, it’s painful to watch as Blanche’s great fall comes to a shattering conclusion. We witness a forlorn, dazed-looking Blanche toward the end. She leaves the Kowalski home with an orderly and doctor. It’s clear she really believes that the doctor is a former beau.

And in a masterful, multi-faceted performance by Kathy McCafferty, the actress vividly conveys Blanche’s many traits.

The performer lends Blanche the skittishness of a deer during mating season. Her wide eyes communicate shock, fear and confusion. That look, combined with a loud, panicky voice and nervous gestures, suggest a woman on edge.

Meanwhile, vivid, symbolic sound effects accentuate the dizzying feelings Blanche experiences. These realistic-sounding effects, by Abigail Nover, include the jarring sound of a passing streetcar. Also, mournful singing reinforces Blanche’s sad, lonely feelings.

As McCafferty embodies her, it’s easy to feel for Blanche. Sure, this sensitive, trusting and seemingly unblemished, refined beauty is not without blame. And to her credit, the actor never pretends Blanche is perfect. Quite the contrary, her superior airs, loud voice and a tendency to dodge questions suggest a woman hiding something. Yet, when she needs to, McCafferty endows Blanche with a radiant, charming joy, buoyancy and zest for life. As a result, we yearn for her to be happy.

But Stanley Kowalski sees right through Blanche’s facade.

Indeed, in this production, palpable tension permeates the stage. It exists between Stanley’s realistic world and Blanche’s universe of magic and illusion. Further, Gavigan, with beefy, muscular arms and an unshaven face, conveys a primitive, common, almost savage and bestial side to Stanley. It stands in direct contrast to Blanche’s refinement.

And despite his uncouth, some might say disgusting tendencies, Gavigan lends Stanley an unapologetic pride. This is especially apparent when the former serviceman tells Blanche, with conviction, that he’s proud to be an American – and that she better not ever call him a “Polack” again.

When you consider Blanche’s penchant for perfumes, powders and her upbringing, the contrast and conflict between Blanche and Stanley couldn’t be starker. That conflict, along with the thunderous rage with which Gavigan endows Stanley, slowly and credibly builds to the shocking climax that ultimately brings Blanche down.

As Gavigan embodies him, Stanley’s bone-chilling menace and rage would frighten even the most tough-minded person. It sends Blanche into hysterics, running into a corner and desperately trying to escape.

Not that Stella and Stanley’s dwelling, in 1947 New Orleans, is filled with horrors. Sure, shadowy lighting by Kirk Bookman produces jungle-like shapes. But this is meant to symbolize the primitive aspects of Stanley and his poker playing buddies.

To be sure, Stanley and Stella share tense moments. They include violent ones that would make today’s MeToo advocates gasp. However, director J. Barry Lewis ensures the couple seem like a loving pair. No doubt, it’s easy to believe that the couple has lived happily in this home. It is designed spaciously, realistically and with period detail by Anne Mundell. That “realistic frigidaire” which Williams has written about in reference to realistic plays is included in the scenic design. It contrasts nicely with the shadowy, non-realistic lighting.

Just as the home seems spacious and comfortable, Mundell’s design includes claustrophobic details. Surely, they could make someone like Blanche uncomfortable. Combine the jungle-like effects with Stanley and his pals’ wild behavior, and it’s easy to see how a refined lady would feel aghast in such an atmosphere.

Also, you can understand the disbelief Blanche feels at her sister’s living conditions. They are vastly different from their cultured upbringing.

Yet, in this production, which features performers who disappear into their characters, Stella appears fully “at home’ in the run-down, two-story apartment. Performer Annie Grier invests Stella with a content, satisfied aura. It suggests she, indeed, has no plans to move. Grier has created a convincing character who may not like Stanley’s behavior. However, she has learned to use coping mechanisms such as humor to stomach it.

Generally, Grier’s Stella is free-spirited and mellow. She’s a woman not nearly as high-strung as her older sister. But push her too far, as Blanche is apt to do, and this younger sibling can become agitated. And while Grier makes it clear that Stella loves Stanley, she acts convincingly disgusted and even angry when her husband mistreats Blanche, reducing her to tears.

Speaking of upset, one moment is particularly hard for Blanche to endure. Stanley’s former war buddy and current poker friend, Harold “Mitch” Mitchell, represents Blanche’s last chance at true happiness. The pair have discovered they share much in common. Further, Blanche has found a trusted friend, even potential beau amid this “jungle” of poker-playing “brutes.”

Brad Makarowski invests Mitch with a kind, if awkward and modest demeanor. He seems rather out of place among the unrefined poker players. The actor nails Mitch’s tender-heartedness toward Blanche. With his soft voice and soothing expression, it’s no wonder she instantly likes him.

But when Mitch uncovers the truths behind Blanche’s façade, Makarowski deftly segues into a bitter man. Clearly, his suddenly spiteful attitude hurts Blanche as much as her deceit has hurt him.

Under Lewis’ detailed direction, Williams’ poetry never gets lost amid the coarse expressions.

At times, performers speak over each other. However, that mainly occurs at the beginning. This is when Stella and Blanche are so excited to see each other, they can barely contain their enthusiasm.

Generally, the action moves at a cinematic-like pace. It never drags, despite the play’s roughly three-hour run time.

Sure, Streetcar is a long play. But, it has much to say about many topics. They include marital relationships, sexuality and sexual desire, mental illness, delusions and illusions, masculinity and male dominance, dependence, the contrast between a person’s exterior and interior and femininity.

Certainly, modern patrons will view some themes through a different prism than audiences who saw the play when it opened on Broadway in 1947. For instance, MeToo advocates might gasp at some of the violence toward women. These days, some directors have grappled with how to handle such scenes. In this case, without being too graphic, Lewis includes these scenes. Good for him.

The role of live theater isn’t to shield us from issues and concerns, even if they’re seemingly concerns from the past. Indeed, their depiction on today’s stages makes us ponder how they might be affecting modern society and what to do about it.

Great plays not only speak differently to different generations, but make us think. And works such as Streetcar absolutely align themselves with Dramaworks’ tagline — “Theatre to Think About.”

Palm Beach Dramaworks’ production of A Streetcar Named Desire continues through Nov. 3. For tickets and showtimes, call (561) 514-4042 or visit palmbeachdramaworks.org. The theater is located at 201 Clematis St. in West Palm Beach.