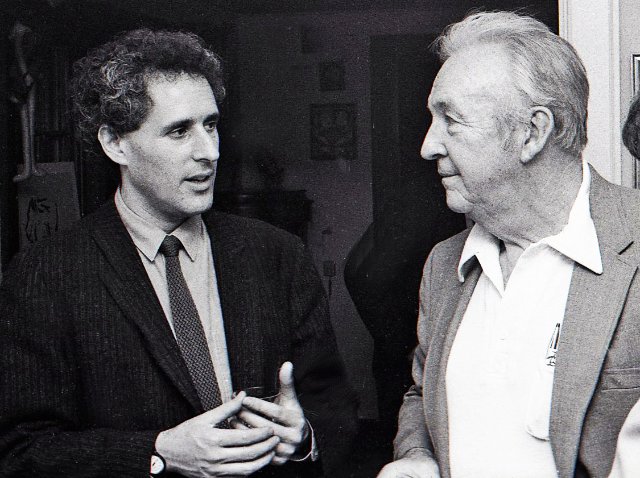

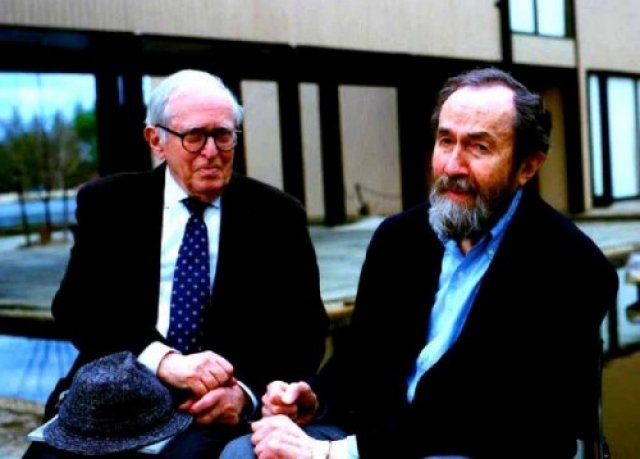

Nick Capasso of Fitchburg Art Museum

Responding to Diversity and Social Justice

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 15, 2020

After 22 years as a curator of the deCodova Museum, Dr. Nick Capasso, for the past 8 years has been director of the Fitchburg Art Museum. It is one of the poorest regions of the state. The community is 35% Latino and 55% of school children speak Spanish at home. The museum is unique for its bilingual initiatives and community outreach. There is diversity in all aspects of its exhibitions and programming. The museum shows New England artists. The collection has grown with an emphasis on photography, African, African American, and American art. Meeting daunting challenges the Fitchburg Art Museum is a remarkable success story.

Charles Giuliano How long were you at the De Cordova Museum?

Nick Capasso My last day was December 6, 2012. I was at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum for 22 years as a curator and for a brief period I was acting director.

CG Why did you leave deCordova?

NC There were a lot of reasons. I was probably there too long and wanted to make the transition from curator to museum director. I wanted a position where I was learning new things. It’s fun to be a curator but I had done that.

CG Your focus has been on sculpture.

NC That’s because of my association with deCordova and my work with public art. I’ve curated shows in every medium not just sculpture.

CG I have been researching the sad story of contemporary art in Boston. In terms of museums, which institution had the mandate for exhibiting and collecting it? The Museum of Fine Arts has taken notice fairly recently and disjunctively. The founders of the museum, now 150 years ago, stated a responsibility to support Boston artists. That manifested in the establishment and programming of its Museum School.

That commitment and synergy phased out in the early 20th century. It changed when the prominent Boston artists morphed from what Trevor Fairbrother’s show characterized as painters of an “Elegant Age” to the Jewish Boston Expressionists who emerged in the 1930s. Starting in the 1980s the MFA began shows of the Museum School’s “Traveling Scholars.”

Similarly, the Institute of Contemporary Art had an erratic relationship with local artists other than the off and on Boston Now series and more recently finalists for the Foster Prize. A rare exception was Lia Gangitano’s 1995 exhibition “The Boston School” (Nan Golden, Jack Pierson, Philip Lorca-DiCorcia, Taboo, Stephen Tashjian, Shellburne Thurber, and Mark Morrisroe.)

When the MFA and ICA arguably passed on Boston artists who stepped up? That fell primarily to deCordova, The Danforth Museum, and the former Fuller Museum of Art which is now focused on crafts.

Carl Belz morphed from the Brandeis art history department to become director of the Rose Art Museum. After directors Sam Hunter and Bill Seitz, the museum fell on hard times. Philanthropy had dried up and Belz had a minimal budget. He embraced and exhibited local artists primarily because that’s what the museum could afford. That changed when Lois and Hank Foster funded the museum. There was a major exhibition during commencement. Directors after Belz pursued other priorities.

On your watch what was the mandate of the deCordova?

NC The mandate changed on my watch. When I started in 1990 as the assistant curator the mandate was exhibiting and collecting contemporary New England artists. We were collecting from post 1950, when the museum was founded, to the present.

During the time I was there, the deCordova amassed the most comprehensive collection with an emphasis on Boston art of any museum in the area. The collection is still there but I don’t know what they are doing with it.

CG How extensive is the collection and where do they store it?

NC It’s a few thousand works but I don’t know the number now because I haven’t been there for some time. The works are catalogued and stored primarily off site. There are some things on site but most of it is off site. When director Paul Master-Karnik left after some 24 years, the search committee decided that one of the charges would be to take the museum to the next level.

The code of that was “let’s stop with this local stuff.” They hired Dennis Kois who had a new mission for the museum that started in 2008. He changed the mission from New England art and focused on the sculpture park as the museum’s unique, differentiating aspect.

The larger context is that, when I first came in 1990, all of the museums in Massachusetts had room in their programs for regional artists. You could even count on the MFA doing a Michael Mazur show every couple of years. Over time that dwindled. What happened to those institution was the same as what happened to the deCordova. The List, ICA, Rose grew and wanted to attract more wealthy, connected, and powerful trustees. These individuals did not want to be associated with museums that were showing the local-yocals. They wanted to be associated with museums which were showing blue chip, international art stars. That changed the landscape and also happened at deCordova.

A very important part of the ecosystem for Boston art was stripped out. When I started in 1990 there was a robust market for contemporary Boston artists. There were identifiable collectors and collections. There was a substantial gallery system for a city the size of Boston. Most of that has collapsed. Because there are no longer museums showing, collecting and validating work that collectors might be interested in. There are other forces at work as well.

There is the art fair phenomenon and general concentration of wealth in coastal cites and all kinds of things going on. These forces came together to limit sales for Boston artists. That has been a gradual process over the past 30 years.

When I came to Fitchburg one of the first moves we made was to launch a major exhibition program for artists. We did that for several different strategic reasons. One reason was that we could do this work fairly quickly and inexpensively. I could leverage 25 years of excellent relationships with artists and dealers. When you work for a long time, and don’t screw people, they are happy to help when you need it. I leveraged my own experience.

As you know, one of the major expenses of loan exhibitions is shipping. If we could curate locally, we could focus our resources on doing excellent exhibitions.

At the time the Fitchburg collection was a hodgepodge of things. Nobody was going to schlep out to Fitchburg to see its collection. You had to offer people something unique. Everyone else had stopped showing contemporary New England artists. The Danforth was closed for a long time. We grabbed that niche.

We knew that it would be very hard to sustain the Fitchburg Art Museum based on local philanthropy because it’s the poorest region in North Central Massachusetts. The philanthropy there is limited and primitive. There is nothing there for the arts.

In order to appeal to people who might be interested in supporting us in Boston and Metro West we had to offer something worth coming to Fitchburg to experience.

When you put it all together there are a lot of overlapping strategic and tactical reasons for making this decision. We started this program in 2013 and have kept to it ever since. By all measures it’s been a great success.

CG How do you measure success?

NC There are a number of ways. One way is by the amount of press you receive. When I got here the Globe had not covered Fitchburg in a decade. The museum I took on had been in a coma. A decade later our exhibitions are covered in what I call the trifecta of Boston press; The Globe, WBUR, and WGBH. We get regular coverage by those platforms.

That increases attendance which you can measure. It also increases the interest and attention of audiences in Boston and Metro West as well as its philanthropy. All of these things have happened.

When I started the annual operating budget was about $850,000. Last year, before the pandemic, we were up to $1.4 million. For a small museum that’s a radical increase over a short period of time.

It’s also helped to build our collections. We have attracted the attention primarily of photography collectors. When I came, we had 700 photographs and at the end of this year we will have in excess of 3,500 photographs.

CG Who are some of the collectors and artists?

NC The primary individual is Anthony Terrana one of the major photography collectors in New England. For a long time, he had been a trustee at the ICA. If you ride in their fancy glass elevator it’s the Anthony Terrana elevator. He’s given the ICA photos over the years. He also had a relationship with deCordova. The senior curator, Rachel Lafo, organized an exhibition from Dr. Terrana’s collection in 2008. (He is a now retired periodontist.)

For a variety of reasons Dr. Terrana was not able to maintain productive relationships with the ICA and deCordova. He was looking for a museum where his philanthropy would be transformative. He and I had a relationship over the years. He decided to direct his philanthropy to the Fitchburg Art Museum not only with gifts of artworks but also, he supports a curatorial program.

We’ve also had a lot of help from Gus Kayafas. As you know, he has relationships with photo collectors all over New England. He has been suggesting to his clients that when they are ready to gift works that they come to Fitchburg Art Museum.

This past week we were approached by a company in New Jersey that represents a consortium of collectors of contemporary photography. They like to make large gifts of contemporary work to museums. One of these collectors is an alumnus of the Groton School which is not far from us. They did a little research and remembered the Fitchburg Art Museum and saw our commitment to photography. They decided that this year’s gift will be just shy of a thousand photographs to our collection. These things build over time.

CG It has long been true that Boston’s painters and sculptors get little or no respect beyond route 128. An exception is the field of photography which has many Bostonians and regionalists with national and international reputations. One thinks back to when Minor White ran a program at MIT. He was director of the Creative Photography Laboratory from 1965 to 1974. Not far away, Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind taught at Rhode Island School of Design. Carl Siembab showed photography on Newbury Street as did later Brent Sikkema and Robert Klein. There was the Photographic Resource Center at Boston University. Other galleries showed photography including, Gallery NAGA, Bernard Toale, and Howard Yezersky who represented John Coplan.

The interest in, and practice of photography in the community created a critical mass. It makes sense for your museum to focus on that medium.

NC There were multiple things happening in the Boston area around the medium of photography that helped to give it a big leg up. Part of that was MIT with not just Minor White but Doc Edgerton. There was the presence of Polaroid and its Kennedy Gallery in Cambridge. Today, we tend to forget about Polaroid as an antique medium which got phased out by the development of digital photography.

Polaroid was a powerful presence and did a lot to support artists.

There were also important collectors. People think of the Lane Collection at the MFA as primarily about modernist American painting. Bill and Saundra collected many American photographers. The first gift of photography to the Fitchburg Art Museum was from the Lanes. In the 1980s they gave us three Charles Sheeler photographs. That started our photography collection.

There were schools of photography in Boston. Mass College of Art always had a strong presence. At one point a member of the faculty bragged to me that not only has every member of the department received a Guggenheim Fellowship, but so did their lab technician.

In addition to that strong base as photography, in my opinion, has become the dominant medium of the 21st century and the dominant market, there were artists in Boston poised to take advantage of that. People like Abelardo Morrell, Rania Matar and others. The point is that there are a lot of established photographers in Boson whose careers really took off about ten or fifteen years ago.

CG Arlette and Gus Kayafas are a factor in that. She with the gallery and he for custom fine art printing.

NC Gus’s Palm Press is nationally known for fine art, black and white printing. They now do color as well. Boston, notably for a city its size, has two galleries focused on photography, Gallery Kayafas and Robert Klein. Most cities the size of Boston don’t have any photography galleries.

There’s also the Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester. There are museums around here with major photography collections: The MFA, The Addison Gallery at Phillips Academy in Andover, deCordova, and Worcester Art Museum. Worcester was one of the first American museums to collect photography as an art form.

CG One might add that collecting photography is not stressful for museums in terms of storage. Compared to racks for paintings, and collections of sculpture, flat files are relatively compact.

NC Exactly. That’s one of the reasons that we collect photography. There is also the factor of price. Even though the market has heated up it is still relatively affordable. It’s something that small museums like Fitchburg and deCordava can collect in bulk. You can aggressively collect photography in a way that is not possible for painting and sculpture. In New England, sculpture has always had a hard time. Most of the commercial galleries show very little of it. They can’t sell it and I attribute that primarily to architecture. If you live in an old house in New England the rooms are small. The new residential homes are based on a New England vernacular so you still have a lot of small rooms.

In Texas and California there are capacious homes. The studio furniture movement got a leg up in New England because people who wanted to collect objects for small domestic spaces could combine design, fine arts and function.

I would say that the New York galleries and Clement Greenberg destroyed whatever market there was for the Boston Expressionists. What else destroyed it was the shear lack of attention paid to it until extremely recently by the Museum of Fine Arts.

If you go to their American wing the first floor is a celebration of John Singleton Copley. The second floor is a celebration of John Singer Sargent. Given that thinking, if you go to the third floor it should be a celebration of Hyman Bloom. It is not.

There’s a specific reason for this and it’s Anti-Semitism. There it is and I’m not afraid to say it. During the 1950s, when Bloom, Jack Levine, Karl Zerbe, David Aronson and Arthur Polonsky were at the height of their powers they were regarded as dirty ghetto Jews. They were and they were not going to be shown and collected at the Museum of Fine Arts. The MFA has a long history of Anti-Semitism.

(On Newbury Street, Boston Expressionism was represented by the Boris Mirski Gallery.)

The MFA is not the only institution that is Anti-Semitic. Just look at their boards. There are a lot of wealthy Jewish people in Boston. The Boston Ballet figured it out and had the first crack at them. That’s when the other institutions figured it out. It was as late as the 1970s.

I’m not an expert on this but it was not until the 1970s that the MFA cultivated Jewish people. That’s all I want to say about it.

CG The first Jewish trustee was Sidney Rabb in the mid-1950s when Perry Rathbone was director. He was later president of the board. By the 1970s, that increased and Jewish patrons underwrote the Foster Gallery and Remis Auditorium and more recently the Linde Family Wing. Mr. and Mrs. Paul Bernat were patrons of the Asiatic department. Under Rathbone she joined the Ladies Committee and became a trustee in 1966. Lisbeth Tarlow joined the board in 2010 and was later Vice President. In recent decades there have been a number of Jewish trustees.

(Social justice initiatives have resulted in significant changes for American museums. The New York Times reports “Now, in an effort to formalize those conversations and facilitate meaningful change amid the Black Lives Matter movement, several of those trustees have banded together to form the Black Trustee Alliance for Art Museums.

“This is a different moment,” said Pamela J. Joyner a member of the alliance’s steering committee who is a trustee at the Getty Trust, the Art Institute of Chicago, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Tate Americas Foundation. “I don’t see anybody who isn’t focused on moving a process like this forward.”

In October “The MFA announced the election of Cathy E. Minehan as Chair and Edward E. Greene as President of its Board of Trustees. Nominated in 2019 and officially appointed at the Board’s annual meeting on September 21, the new officers are joined by Azi Djazani, who was elected as Chair of the Board of Advisors. The Board also welcomed three new Trustees and 10 new Advisors, including artists Jeffrey Gibson, Matt Saunders, Jeannie Simms, Gabriel Sosa and Caron Tabb…The MFA's first African American President of the Board of Trustees, Edward E. Greene is a seasoned human resources executive whose involvement with the Museum dates from 2006. He served as Chair of the MFA’s Board of Advisors from 2017 to 2020 and prior to that as Vice Chair.”)

NC By the time the 1980s rolled around there was change regarding Jewish philanthropy. Absolutely.

CG The current emphasis is on inclusion of people of color. When Malcolm Rogers resigned in 2015 there was an overview of his tenure in Boston Magazine. As was reported at that time of some 32 board members two were persons of color. Matthew Teitelbaum has been tasked with addressing that issue.

In news coverage of the National Gallery decision to postpone the Philip Guston show, its director, Kaywin Feldman, stated that the museum had recently appointed its first person of color to the board. That occurred at the MFA in 1972 when Howard Johnson was board chairman.

(She was Phyllis A. Wallace (1921–1993) an economist and activist was the first woman to receive a doctorate of economics at Yale University. Her work focused on racial and gender discrimination in the workplace. As Howard Johnson told me at the time, “She knows the museum well as a visitor. She is one of the nation’s leading experts on equal opportunity. I see Professor Wallace though as not representing any group. I want the trustees to call the shots as they see them and not try to act as representatives of any specific interest group. We are looking for people from diverse backgrounds and points of view to bring their expertise to the board. I personally work with a lot of boards and I always tell them to call the shots as they see them.”

Trustee, Walter Muir Whitehill, objected to her appointment telling the Globe in 1973 that “I would say that the Board of Trustees is a fiduciary body that has to administer an institution and can’t and should not be reflective of every element in the community. Such a board becomes unwieldy and unworkable. You know what Calvin Coolidge said when someone called a member of Congress a son-of-a-bitch. ‘Well there are enough of them out there, so I suppose they are entitled to representation.’ ”)

Responding to accusations of racism the MFA has pledged $500,000 toward diversity and inclusion. In May it launched a department of Learning and Community Engagement, headed by Makeeba McCreary.

NC A few years ago she visited us in Fitchburg. She came with a staff person (from Northeastern University) because she had learned that our museum had made a major pivot to community service. She came to learn what we were doing. What attracted her is that Fitchburg is one of the nation’s few bilingual museums.

Some 35% of people in Fitchburg are Latino. In the public schools 55% of the students speak Spanish at home. Accordingly, all the text in the museum is in English and Spanish. Our receptionist is bilingual. We do programming with other nonprofits that serve the Latino community.

CG To return to the Boston Expressionists you have written on the subject which I have quoted. Can you give me a sense of where they fit into the perspective of American art history?

NC If you’re writing the history or art in your region, or are looking at the history of art in America through the lens of Boston, which is what the MFA does, to ignore the most important development of art in your city during the mid-20th century, is kind of odd.

The Boston Expressionists got marginalized because of the hegemony of abstract expressionism. The figure was verboten for a long time. There was, however, a core group of artists in Boston who kept at it for many decades. They made great paintings and were important not only for the art work but for the pedagogy. They were professors and instructors in all the major art schools in the city. It’s telling that this is where Philip Guston fled to when he dared to challenge the hegemony of abstract expressionism. He ran to Boston because there was a context for him there. David Aronson hired him for BU. (From 1973 to 1978 Guston taught a monthly graduate seminar at the Boston University School of Fine Arts.)

Boston with a long history of expressionism welcomed Guston who helped to launch neo expressionism in the 1980s. It’s an important part of our history and you don’t erase it just because other things are happening in other cities. Or you don’t like the ethnic background of the people who are creating the art.

It’s what happened here. Hyman Bloom was incredibly important. Could Bloom have played the game better? Sure, but he wasn’t interested in doing that. He was his own mercurial person. But you can’t argue with the quality of the work.

CG Does Fitchburg have any representation of Boston Expressionism?

NC No. The collection I inherited was a hodgepodge from ancient Egypt to the present which has washed up at the Fitchburg Art Museum for one reason or another over the years. What (former director) Peter Timms was trying to create was a faux encyclopedic museum. There was a little bit of this and a little bit of that. He was trying to provide an introductory experience for visitors in a city that shouldn’t have a museum in the first place.

We changed that because we have the Worcester Art Museum a half hour down the road so we didn’t have to try to be an encyclopedic museum. We decided to build with an emphasize on the actual strengths of the collection which we identified as photography, African art, and American art. We do collect New England artists but as they relate to those collections. We are not trying to do what deCordova did. We are not trying to create a comprehensive collection of New England art. We don’t have the resources to do that.

We are aggressively showing the work of New England artists in group and solo exhibitions. But it’s not a collection priority for us. The torch bearer for Boston Expressionism is the Danforth Museum. (That mandate was created by former director Katherine French.)

CG I get calls from heirs asking for advice on how to market the work and place it in museums. It takes a lifetime to create a market for the work. If that isn’t established during the artist’s lifetime it’s a daunting task for the estate. With some exceptions there is not a strong secondary market for contemporary New England artists.

NC Handling an estate only works if it is done by a major gallery which makes an effort to place the work in museums and collections to ensure a market going forward. If those conditions don’t apply it’s a real uphill battle. A lot of artists fall out of art history because their estates were not well managed or mismanaged.

CG There are interesting success and failure stories in that regard. A lot depends on the acuity of heirs and the commitment of galleries who represented the living artist. A great example of a well-managed estate is that of Milton Avery. His wife, Sally, supported him during his lifetime allowing him to work. That partnership continued after his death and she was remarkably shrewd.

On the other hand, consider the example of the leading Provincetown artist Karl Knaths. He was regarded as one of the leading three artists of the WWI generation when the Provincetown Art Association was founded. The other two were Ross Moffett and Edwin Dickinson. He was represented by Pierre Rosenberg Gallery in New York. During many winters he taught at the Phillips Collection and Duncan Phillips was his primary patron. The museum owns a number of his works.

He and his wife Helen had no children. Today, work by his sister-in-law, Agnes Weinrich, is sought out by collectors more avidly than that of Knaths. Initially, the estate was managed by the Cape Cod banker Ken Demaris. He tried to provide income to Helen who survived to be the oldest living Provincetown resident. The banker had no knowledge or interest in art and became impatient with the few sales by the Rosenberg Gallery. He ended the relationship and the work was sent to the bank which basically liquidated it to the dealer Ed Shein. He in turn sold works to investors that were donated as tax write-offs to the Fuller Museum of Art and Danforth Museum. The market for the work collapsed and has taken decades to recover.

(Ed Shein called with clarification. The Cape Cod banker Ken Demaris offered him the Knaths estate in 1972 on consignment with an agreement to sell paintings for $2,400 each of which commission would be $600. With a couple of friends he loaded 125 paintings into a van collected from the Paul Rosenberg Gallery in Manhattan. A short distance away there was a rendezvous with the Woodstock, New York collectors Jim and Jean Young. She had been a student of Knaths. According to Shein they “cherry picked” forty paintings. Prior to this, Rosenberg had slowly been selling paintings for an average of $10,000 but not enough annually to satisfy the banker. Shein sold another 25 or so to collectors. What remained was sold in bulk to individuals “who kept them for a year or two before they were donated to several museums with a tax evaluation of some $6,000 each.” I saw those works at the Danforth Museum and Fuller Museum of Art. I traveled to Woodstock to see the Young paintings which had been divided with a backer. They had an early portfolio of Knaths monotypes circa 1913 when he arrived in Provincetown. Some were signed “OK” and others “KK.” His birth name was Otto and he changed it to Karl at that time. He did not want to be confused with the signature of Oscar Kokoschka. The abstract monotypes were remarkable and compare with works from that time by Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe and other modernists. The banker dismantled important sketch books which sold inexpensively with either an estate stamp or an ersatz Knaths signature. Shein is unaware of any drawings and is only interested in paintings. There was a 1982 Bard College retrospective “Ornament and Glory” that combined paintings and drawings. It assembled his theoretical essay. Drawing upon local sources I organized a show for the Boston University Art Gallery. The Museum of Fine arts had a large disassembled work on masonite which was not available to borrow. His best picture “Lilacs” which I remember well when it was often on display at the MFA was deaccessioned by Ted Stebbins. Shein states that the artist’s best works are in (31) major museums like the Whitney, Albright Knox, Met, MFA, Art Institute of Chicago, and Phillips Collection. “If there was a well curated show of his forty best works we would think differently about Knaths today.”)

NC I’ve been talking with black artists in Boston and there is a huge concern that their work is being lost to history. The major figures have been neglected. Another artist (like Bloom) that the MFA should have shown 40 years ago is Alan Rohan Crite. When is that show going to happen?

CG If the MFA isn’t interested then why not Fitchburg?

NC I’m thinking about it. Our African collection is based on traditional tribal arts. We also show and collect works, from around the world, that reflect the tribal traditions. Mr. Crite had tons of work like that. Just before the pandemic hit, we were in touch with (his widow) Jackie Cox Crite to start a conversation about this. That got delayed. I would like to get back to her about that. There are a few things by Mr. Crite that we would like to acquire. We don’t have the resources to do a comprehensive retrospective and catalogue. A 200-page publication is what needs to happen. We can certainly show his work as it relates to the African diaspora.

CG You might contact Arthur Dion. Some years ago, he organized a Crite show in Rhode Island and exhibited the work at Gallery NAGA. I met Jackie and know that she is dealing with a lot of projects. Jean Gibran organized a show of the work at the St. Botolph Club and managed to get loans from the Boston Athenaeum which has a body of work. Unfortunately, the show opened just when the club was shut down because of the pandemic. I had planned to see it but that never happened.

Can you tell me about some of the African American artists you have been in touch with?

NC There is a group of African American artists and educators in Boston and they are calling themselves Where Are All the Black People At. Their mission is to educate art museums that the lack of presence of artists of color in their permanent collections is a social justice and racism issue. They are trying to encourage museums to collect work by people of color. They are reaching out to start these conversations. I met not too long ago with four individuals. The photographers Archie LaSalle and Lou Jones. professor Reginald Jackson who teaches at Simmons College, and another professor Sharon Dunne who teaches at Mass Art.

We had a very interesting conversation about these issues. They’re talking with the Houston Museum of Fine Arts and other museums.

CG Can you give me a sense of the depth of this community of artists in Boston? On my watch it was sporadic. An exception was Wendell Street Gallery in Cambridge which showed my friend Benny Andrews as well as Boston artists. Benny was in a show I curated for the Provincetown Art Association, Kind of Blue: Benny Andrews, Emilio Cruz, Earl Pilgrim and Bob Thompson. They all had summer studios in Provincetown. That show then traveled to the gallery of Northeastern University.

Barry Gaither curated five major exhibitions for the MFA and was director of the National Center of Afro American Artists in Roxbury. In 2011 the MFA acquired 67 works from John Axelrod a former trustee and head of the diversity committee.

NC The major artists were John Wilson, who taught at BU, and Dana Chandler. Dana was an artist/ activist who helped to create the Afro American Artist in Residence Program at Northeastern University. A lot of artists had studios there over the years; Keith Washington, Napoleon Jones Henderson, Barbara Ward, and Hakim Rakhid. And, of course, Mr. Crite who was the dean of the whole thing.

CG I discussed that with Chandler and he told me “I got that space in return for teaching a course in the African American Studies Department. I was available for students to come and talk about art and explore my studio. That's what led to AAMARP because it was on a floor of a building that had a 32,000 square foot space. I presented a proposal for the creation of an African American artist’s complex that would have studio spaces and galleries as well as a community space for all kinds of events. The community space was about 4,000 square feet. It's still there but not in that building. It's at 76 Atherton Street on the Roxbury side of the old Jamaica Plain.

“I started off with 13 or 14 fellows. Ellen Banks and Milton Derr (who also taught at Northeastern University). Others included Tyrone Geter, Reggie Jackson, Arnold Hurley, Jim Reed, Rudy Robinson, Barbara Ward, and Teresa Young. These artists were actually in residence. Calvin Burnett and John Wilson were associate artists who had their own spaces. They were connected and exhibited with us whenever we had shows.”

NC It’s been hard for these artists not only to sell work but even to get shows. The advocacy group is trying not just to get artists to have shows but for museums to acquire their work.

CG When they met with you did you get the sense that they represented a critical mass of artists?

NC Archie is supposed to send me a list but they have a dozen or so artists that they consider to be masters who work in the Boston area and deserve greater attention. I am probably forgetting people.

CG The memory lapses of individuals such as ourselves, who have been in the field for decades, is a manifestation of systemic racism. I had an intense conversation with a prominent actor with whom I have had many interviews over the years. We discussed changes in theatre in the wake of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter. He stated that I was a white supremacist because I accept the circumstances of white privilege. He told me that moving forward critics will have to deal with that when reviewing experimental black theatre. We had a lively discussion of “The Slave Play” which I thought was “flawed” and he regarded as a breakthrough. I was applying critical standards which he regarded as obsolete.

That conundrum surfaced when four museums recently cancelled the Philip Guston show with its Ku Klux Klan imagery. It is a fact that no individual of color was involved with the project. New paradigms are being explored and developed for critics, curators, cultural practitioners and educators.

NC A lot of it has to do with racism not in animus but in preference. There are museum professionals who bear no hatred of black people but just find it easier and more comfortable to deal with white people.

CG So passivity is racist?

NC Yeah. This an argument made about hiring practices. It’s not that you don’t hire black people because of hatred. You hire white people because you know them better.

CG What is our museum doing to address systemic racism?

NC We are doing a lot. Because of the African collection our collection has a very high percentage of people of color. We have collected work by contemporary Latino and African American artists. We show that work fairly regularly. When we do group shows of contemporary New England artists, we try to include people of color.

Recently we did a very large Daniela Rivera exhibition. She is arguably the most important Latina artist in New England at this time. We did a major show last year and we continue to think curatorially in this direction.

(Born in Santiago, Chile, Daniela Rivera received her BFA from Pontifcia Universidad Católica de Chile in 1996 and her MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts, Boston in 2006. She is currently an Associate Professor of Studio Art at Wellesley College. She has exhibited widely in Latin American cities including Santiago, Chile, as well as in the United States. Rivera is the recipient of the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum’s prestigious 2019 Rappaport Prize.)

We do a lot of work with our local Latino community in terms of outreach and access. We have outreach responding to George Floyd, Briana Taylor and everybody else. I finally got the board to stop talking about diversifying the board and actually start doing it. This December we are bringing onto the board two individuals from the community.

CG How large if the board?

NC We have 20 and are bringing on two but are not stopping there. This is the first step. The goal is for the board adequately to represent the demographics of the community. In the next few years, we need to have 30% people of color on the board. But we are not putting people on the board willy-nilly in a tokenized way. It takes a while to establish relationships in the community. We are trying to do this the right way.

We have staff from the Latino community. Our bilingual receptionist is Dominican. Our collection manager is Puerto Rican. He grew up in Fitchburg and we kind of home trained him. We are creating a task force to coordinate these efforts across various committees of the museum.

We are in the middle of writing a racial justice and equity policy which will be approved by the trustees. We’re doing a lot and have lots of partnerships within the community.

CG It’s great to talk with you as so much of this is timely and relevant. This represents a small regional museum taking a position of leadership.

NC What’s going to soon happen is that major foundations that support the arts, and other non-profits, for two decades have been gently encouraging their grantees to do this work. I think the gentle approach will be coming to a screeching halt. I think they’re going to drop the hammer. The foundations exist to create social change.

The Pew Charitable Trust, the Boston Foundation, they want to change the world and are losing their patience. They’re making racial justice a primary aspect of their missions. Pretty soon they will be requiring nonprofits to have racial justice and equity policies. To have committees that deal with these issues or they’re not getting money. The same way that they require non-profits to have financial audits. They are going to make the same requirements for social justice and equity work. That will force institutions to do the work.

CG I would like to go back to issues of Boston Expressionism. One of the first exhibitions under director Paul Master-Karnik at the deCordova was Expressionism in Boston: 1945 to 1985 curated by Pam Allara. My review at the time was very critical. I felt that it had been done so poorly that it would set back interest in Boston Expressionism by decades. Indeed, it was 2019 when the MFA mounted its Bloom exhibition. There was even an image in the deCordova catalogue printed upside down. The show was largely inept.

NC That predated my time at deCordova so I never even saw that show.

CG While well intended I didn’t think that Master-Karnik was the brightest bulb on the tree. But he sure had an ego.

NC Yes, he did.

CG As a critic covering the deCordova the museum felt like a chronic underachiever. Their mandate to exhibit and collect the art of New England was unique and important. But too often that energy seemed misdirected. There wasn’t the acuity of other museums in the region focused on contemporary art like the ICA, Rose, or even the Addison Gallery. A lot of the exhibitions could have been better. It’s not easy to say that to a former deCordova curator.

NC The quality of the shows was uneven. I think, over the years, they gradually improved. When Paul Master-Karnik came in he put a lot of emphasis on the sculpture park. The curatorial mission was kind of bifurcated. One the one hand were New England contemporary artists and on the other hand it was trying to establish a national presence with large outdoor sculpture. It didn’t have the staff and resources to do both well.

CG What I am admiring from afar is an effort to right some wrongs. One of which was certainly your Otto Piene show a couple of years ago. For whatever reason, art/ science/ technology, exemplified by the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) which Otto headed at MIT, was world renowned yet ignored by Boston’s museums and the art world. In later years Otto showed regularly with Sperone Westwater Gallery in New York and had a number of exhibitions in European museums both solo and with Group Zero. I curated a show of his works on paper for New England School of Art and Design which proved to be a rare Boston exhibition foe Otto. The deCordova later showed the work and there was discussion of a major exhibition at MASS MoCA but nothing came of it. The Fitchburg show was posthumous but superb.

NC Even MIT’s List Visual Arts Center, under Kathy Halbreich and her successors, had no interest in CAVS. Even though the List is housed in the same building with the Media Lab. They never talked to each other.

The deCordova included Otto in an annual show. They were also showing a lot of video art curated by George Fifield (founded the Cyberarts Festival). Another CAVS fellow who got major attention was holographer Harriet Casdin Silver. I did her retrospective for deCordova.

CG My wife Astrid Hiemer worked for CAVS as an administrator and Harriet was one of her close friends. I wrote an essay for Harriet’s deCordova catalogue. A couple of years ago there was a CAVS show and colloquium produced by the MIT Museum. Many of the fellows gathered for that event.

NC As opportunities present themselves, we hope to focus on artists and phenomena that have been neglected by museums. An Alan Rohan Crite exhibition is an example of our projected programming.

The Otto Piene project fell into our lap. He had said a number of times to his wife, Elizabeth Goldring, that he wanted to have a local show. His work is known all over the world but not here. Elizabeth is good friends with one of our trustees. We got together and discussed possibilities. Fitchburg is close to Groton where Otto resided so that’s how this came about.

We were very lucky. The market for Piene is very hot right now. There’s a gallery in Berlin that’s aggressively selling his work as well as Sperone Westwater. It was a coup for the Fitchburg Art Museum to do a big Piene show.

CG How was the show received?

NC It went over extraordinarily well. It was a great show for people who do not know a lot about contemporary art because you could certainly learn a lot. With Otto everything is a spectacle. People love that. There was a lot going on. Everything moved and changed. The audience liked it and it was also good for us. It gave the museum some street cred. It also brought a lot of people who had never been to the museum. There were all those folks who knew him and had connections to CAVS.

CG Do you have any interest in Gyorgy Kepes (founded CAVS).

NC Yes, personally. He was an important artist and theorist.

CG Do you have his photographs?

NC I believe a couple but not a lot. The deCordova has a lot both paintings and photographs. They must have 20 to 30 objects.

CG The deCordova has such an in-depth collection in storage. I realize you are no longer there but what has become of it?

NC I don’t know and I don’t think they do either. They have ceased to exist as an independent entity. They were acquired by the Trustees of Reservations. They are a land conservation nonprofit. Often, when they get a mansion, it is full of stuff like the Crane Estate in Ipswich, Naumkeag in Stockbridge, and other sites. They have a portfolio of what they call cultural properties. In the past few years, they have added to their portfolio with deCordova as well as the Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Mass.

They were both having economic problems and were underendowed. They decided that their survivability would be best vouchsafed by merger. They were acquired by Trustees of Reservations. Now they are trying to figure out what to do with their newly acquired museums. Previously, they have not been in the museum business. Primarily they were in the historic house business. It’s still a process to figure out what to do with these museums.

The deCordova has been organizing many shows from its collection. Over the past several years they haven’t had the resources to do loan shows. When you have economic problems, you fall back on your permanent collection. They have done some really nice shows including, a few years ago, one on women abstract painters, Maud Morgan and those folks. It was a beautiful show. They have great stuff in the collection. But I don’t know the future of that collection.

CG Let me take the pulse of the Fitchburg Art Museum. What are its vital signs?

NC That’s a pretty good analogy these days. We are fortunate not to be having the problems that a lot of museums are having because of the pandemic. The economic model is such that we are not suffering the loss of earned income from being closed for a long time. We are not suffering from a lot of the things that small museums are suffering like debt, holes in the balance sheet, or under-endowment. We are in a sweet spot however getting through the pandemic will be challenging. Though we are in no way engaging in conversations about closing or merging. When this is over the Fitchburg Art Museum will still be there to serve our community.

CG What’s your endowment?

NC That depends on what the market is doing but let’s say $19.5 million. Against a $1.4 million annual operating budget that’s good. It doesn’t support everything we do but keeps the doors open and pays a small staff. All the credit belongs to Peter Timms who built that endowment. He saved the museum in perpetuity. I have not done that. He did that. We are making the edifice he built as relevant as we can for the community and century that we are situated in. He also built a substantial new wing that opened in 1989. It transformed us from a local art center to a regional museum. We have twice as much gallery space as deCordova. We have 24,000 sq. ft. of gallery space. That is due to Peter Timms.

CG I worked with him in 1991 as guest curator of The Object Found, Observed and Imagined.

NC When you visit art museums you quickly get the sense that you are not the client. Art is the client and you are tolerated. Our feeling is that nonprofits exist to serve people not things. We use our things, art, to serve people in whatever way that makes sense for a museum. We are not going to be a methadone clinic, or half way house, but there are lots of ways to leverage what an art museum does to serve multiple communities. That includes economic and community development work.

The flagship project for us is working with multiple organizations to developed abandoned municipal buildings across the street from the museum into sixteen units of affordable artist’s live work space.

There was an article in Commonwealth Magazine that describes how Fitchburg is leveraging arts and culture for revitalization. It describes the museum’s role in that process.

CG How do you work with school system?

NC We have a strong relationship with both the public schools and Fitchburg State University. The school superintendent and the university president both sit on my board of trustees. Every fourth and seventh grade student in the Fitchburg public schools comes to the museum on an annual field trip at no cost to the students and schools. It’s Fitchburg and they can’t afford field trips. If we want the kids to come, we have to pay for it.

We also have a formal letter of agreement with Fitchburg State University. Many colleges and universities have their own art galleries. Fitchburg did not but now they do. We do better work for the students than most colleges do.

CG What’s your annual attendance?

NC Not big. It’s about 15,000 visitors per year. That’s because we are far from our natural audience. We have the lowest educational attainment level in the state. Only 21% of the Fitchburg population have attended college. It’s not a museum going kind of town. But I have to say that it’s easier to do this kind of work in a small museum. We are less cumbersome when reacting to challenge and change. To do this work you need an alignment of the staff, board and community. That’s more challenging for large museums. The change has to come from the top through the director and the board. In the absence of that you can’t do this work. You can’t do this work effectively piecemeal and in silos. I hear from museum professionals that it’s harder to change things at larger museums.

CG Thank you for valuable time and insights.