Williamstown Film Festival: Week One

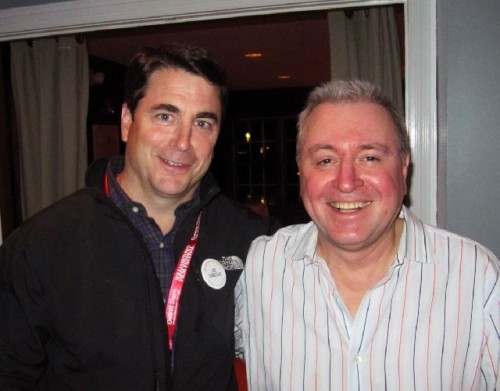

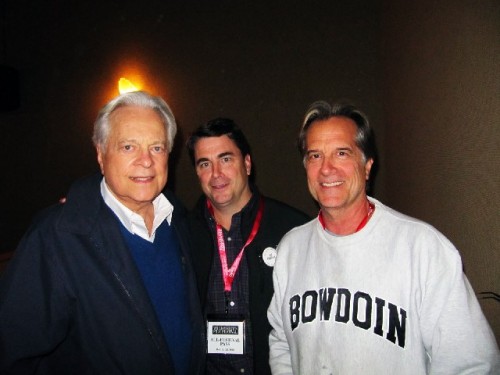

Baldwin and Osborne on Wilder Pack MoCA

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 18, 2010

The first of two weekends of the Williamstown Film Festival was exactly that; a festival, an intimate and insightful celebration of cinema.

The small scale of the event organized by artistic director, Steve Lawson, created a sense of community. There was critical mass of individuals with badges slung around our necks. We met, collided, and interacted with each other. In this monorail of a festival, with a single screening at a time, there was a lot of opportunity to share insights and compare notes.

During the Saturday breakfast seminar “The Kids on the Screen,” at the Williams Inn, we talked with WFF board member Joan Hunter. The conversation included films presented during the festival and her long associations with the Williamstown Theatre Festival, Jacob’s Pillow and Mass MoCA. Everyone was excited about the appearance that night of Alec Baldwin, in conversation with Robert Osborne, on the topic of Billy Wilder. There was table talk about how Osborne, early on, was advised to write about film by Lucille Ball. There was chatter about Lucy and Desi. It focused on his philandering and how Lucy insisted that he co star in her TV series so she could “keep a close eye on him.”

Hunter told an amusing story about Baldwin who worked with Lawson, early on, at WTF. There was very little TV viewing in her family. She recalled a gala in a tent to celebrate an anniversary at WTF. At her table they were going around with introductions. She turned to Baldwin, who has an ego and edge, and asked “And what do you do?” Alec, apparently, was not amused, but Hunter laughed recalling that the other table guests enjoyed his reaction.

Things happen at festivals. Which is why they are so much more interesting than just going to a lot of movies. It is really about the dialogue and networking that brings it to another level. Like listening in as Osborne and Keith Bearden, the writer/ director of the Friday feature “Meet Monica Velour,” conversed during the after party at Mezze.

The scale of WFF, with its one event at a time linearity, makes such interactions and insights a virtual reality. Following the screenings of the three feature films and program of shorts Lawson engaged in dialogues with actors and directors. He is a lively and probing host. The sense of passion and history of the medium was compelling. It added immensely to the enjoyment of a fabulous three days of films.

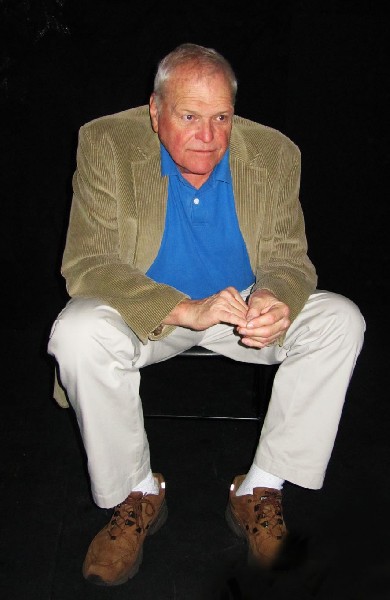

By the nature of the WFF the emphasis is on low budget, independent films, and shorts by emerging filmmakers. The mandate is for these creations to be screened before knowledgeable and appreciative audiences. To try to establish word of mouth interest that helps to find distribution. During the discussion sessions there was the common theme of how to get the films seen and marketed. Brian Dennehy talked about “Hitting the festival circuit” as a means of getting the word out.

But WFF is not likely to make or break any films. It isn’t a market place like the big, established, festivals Sundance, Toronto, Cannes. There weren’t a bevy of heavy hitters hanging around the bars of Williamstown or inking contracts, late at night, in suites at Porches. This was more about a gathering of the cognoscenti who really love movies.

From the 300 and more films submitted, as well as what Lawson saw on his own at Sundance and Tribeca, he assembled a superb program. It was abundantly clear that the three features presented during the first weekend were labors of love. They were films that got made on tiny budgets through the passion and commitment of those involved. All three films were terrific with superb performances by established actors willing to work for short money on projects they believed in. On Friday night we saw “Meet Monica Velour” on Saturday “The Space Between” and on Sunday “Every Day.” The films will be reviewed in another article.

The relevance of the topic of “The Kids on the Screen” would unfold after the Saturday breakfast seminar. By then, we had seen only one film “Meet Monica Velour.” It features a nerdy teenager, Dustin Ingram, who meets and tries to have a relationship with a now past her prime, porn star played by Kim Cattrall. In later screenings we got Lawson’s point as a number of superb performances were evoked from juvenile actors. Before that experience, however, the discussion, while insightful, lacked specific examples. It would have been more effective if that event was switched to the second weekend. By then, members of the audience would have more material to relate to.

Following three days of programming that is my only quibble. That says a lot about the quality and impact of the festival. Although we had mixed responses to the screening of All-Shorts Slot I on Saturday afternoon. The audience was asked to vote for all of the shorts, including the ones that preceded the screening of feature films. At the end of the festival a prize winner will be selected. Lawson told me, prior to the festival, that WFF is particularly known for its emphasis on shorts. WFF provides unique opportunities for emerging filmmakers and actors.

One of the best aspects of WFF was the feeling of a local, neighborhood event. It was such a pleasure to just drive to the festival with no airports and hotels involved. Saturday was a long day but we were able to have a dinner break, at home, before returning for the evening event.

We arrived, about 7:30 PM, hoping to get good seats in the sold out, packed to the gills, Hunter Center at Mass MoCA. The first four rows were reserved for those who attended the sold out, benefit dinner. The evening provided the kind of star power that one anticipates at a festival.

The films of Bill Wilder (1906-2002) were presented in three, nine minute collages. Followed by two of his most memorable highlights from “Sunset Boulevard” and “Some Like It Hot.” The format of the program is that Lawson interacted with Osborne and Baldwin who discussed the clips, their relevance to his oeuvre, and an evaluation of his career in the history of the medium. The dialogue was interspersed between the screenings.

Repeatedly, Osborne astonished the audience with the spontaneity and depth of his knowledge of film, in general, and Wilder in particular. Based on his introductions for Turner Classic Movies I assumed that he worked with a well researched script. On stage, it was amazing to observe him pull together remarkable detail and insight completely spontaneously. Baldwin proved to be a great straight man providing many serendipitous, humorous moments.

There was a clip of Marlene Dietrich singing “Black Market” in the 1948 film “A Foreign Affair.” Osborne floored us by commenting “Did you notice the piano player?” He went on to inform us that it was Frederich Hollander the composer of Dietrich’s standard “Falling in Love Again” from “Blue Angel.” Baldwin mugged and commented to the effect of, can you believe this guy? The audience loved the moment. It was but one of many during a fabulous evening.

More than just a tribute to a great screen writer and director, the dialogue provided many priceless insights into the nature of the medium and its struggles. We learned a lot about the vagaries of casting. Wilder may have had a particular actor in mind but, because of the studio system, it wasn’t always possible. It was fascinating to learn that his first choice for Norma Desmond, the faded film star of the silent era in “Sunset Boulevard,” was not Gloria Swanson, in her most memorable role, but actually, Mae West. He wanted Walter Matthau to play opposite Marilyn Monroe in “Seven Year Itch” (1955) but ended up with the less effective Tom Ewell. There was discussion of the difficulty of working with Monroe, which Wilder did twice. The second produced one of her greatest performances in “Some Like It Hot” (1959). It took as many as 85 takes with Monroe. But, of course, that last take was pure magic.

They talked warmly about how Monroe was a great but deeply troubled artist. Particularly, they noted her bad luck with men. It seems that Joe DiMaggio was on the set the day during the shooting of “Some Like It Hot” when Marilyn’s skirt blew up over a subway vent. He was not amused.

While Wilder, who escaped Nazi Germany for Hollywood, made many great films, (28 between 1934 and 1981 as writer/director) the final collage of clips, revealed the sad decline of a great career with a string of really bad films. It doesn’t get worse than “Kiss Me Stupid” (1964) or “The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes” (1970) which was taken over by the studio, hacked up, and released. Much of Wilder’s original footage was destroyed so there is no way to reconstruct his vision with a posthumous reconstruction. Osborne commented that “A lot of people like ‘Kiss Me Stupid’ but it is not my favorite film.” Baldwin observed that, ironically, the best thing about it is the performance by Dean Martin. Go figure.

Osborne made the sad observation that, although Wilder died in 2002, he made his last film “Buddy Buddy” in 1981. For the last 20 years of his life Wilder was ignored by Hollywood. He is an example of the familiar theme of a great artist who did not manage to keep up with the times. It makes one realize how remarkable it is that Clint Eastwood is still making films in his 80s.

Baldwin noted that, today, movies with high production values have become so expensive, that fewer and fewer directors are entrusted to make those films. Which, of course, underscored the mandate of WFF with its emphasis on small, independent films, and their struggle for recognition.

Osborne recommended Cameron Crowe’s 1999 book “Conversations with Billy Wilder.”

With humor, Baldwin complained about all the homework involved in preparing for the Wilder tribute. There were a lot of films to view and not all of them winners. There are the well known films which most people have seen “Sunset Boulevard” (1950) and “Some Like It Hot” (1959) as well as the more familiar films “Witness for the Prosecution” (1957) “Seven Year Itch” 1955 and the seminal “Stalag 17” which spawned the TV spoof “Hogan’s Heroes.”

During his career Wilder often worked with the same actors including Ray Milland, Monroe, William Holden, Walter Matthau, Audrey Hepburn, and Jack Lemon. There was an interesting discussion of the charisma of actors on and off the screen. The clip with Kim Hunter was curiously enervating. Osborne noted that she was more magnetic on screen than off. But he discussed individuals who would light up a room in Hollywood but were not able to convey that charisma in front of a camera. They commented on how some actors were narrowly cast and limited while a Cary Grant always was great just playing Cary Grant.

The evening revealed many great works which we were urged to check out through Netflix or tivo on TCM. Lawson raved about an early work “The Major and the Minor” (1942) which he had screened as research for the project. There was interesting commentary about the superb “Double Indemnity” (1944) with Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck. Osborne noted how Stanwyck was one of the most professional and widely admired performers of her era. “She always showed up on time and off book” he said. “Usually she knew everyone’s lines.” There were also anecdotes of the difficulty Wilder had working on “Double Indemnity” with the often drunk Raymond Chandler, the gifted mystery writer, who knew little or nothing about the specifics required for films.

Other highly recommended films include the Oscar winning “The Lost Weekend” (1945) with Ray Milland. It was one of the first Hollywood films to treat the subject of alcoholism. Also “A Foreign Affair” (1948) in which the expatriates Wilder and Dietrich returned to post war Germany. It provided some of the first aerial views of the bombed out Berlin. They recommended “Sabrina” (1954) a charming film with Audrey Hepburn and a miscast Humphrey Bogart. Wilder wanted Carey Grant for that role. Check out “The Apartment” (1960) “Irma la Douce” (1963) or “The Fortune Cookie” (1966).

During his long and productive career Wilder received eight nominations for best director in the Academy Awards. He won twice for “The Lost Weekend” and “The Apartment.” He set a record with “The Apartment” for which he won three Oscars (Best Film, Best Director, and Best Screenwriter).

As is so often the case artists are not always recognized for their best work. In 1959 “Ben Hur” swept the Academy Awards. “Some Like It Hot” received only one award for best black and white costumes. Osborne noted that such great films as Truffaut’s “400 Blows” Bergman’s “Wild Strawberries” and Wilder’s “Some Like It Hot” lost that year to the forgettable fluff “Pillow Talk” for best screenplay.

Osborne, our greatest authority on the Academy Awards, ironically observed that the awards do not always honor what prove to be the most enduring works. Indeed.