Mussorgsky's Original Boris Godunov at the Met

How Do we Assess Versions

By: Susan Hall - Oct 18, 2021

Alternate versions of an opera arouse controversy.The multiple versions of Verdi’s grand opera Don Carlos (Don Carlo) were a response to different productions. Terrence Blanchard adapted his opera Fire Shut up in My Bones for the Metropolitan Opera’s stage.

Originally produced by Opera Theatre of St Louis, the Met production of Fire added meat and melody to the role of Uncle Paul. Blanchard wrote an additional aria for Billy, the mother, sung exquisitely by Latonia Moore. Scenes were extended (padded?), many words spoken in the original are now sung. Six dancers became a troupe of 12. A chorus of 10 became a chorus of about 40 voices. The orchestra is expanded to seventy pieces with an embedded jazz ensemble. These changes were made so that the work would play in a much larger venue than the one for which it was originally created.

Running in repertory with Fire is Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Godunov is deeply political. Its history is foundational in Russia. Fire is not a political tale. Rather its mounting is a political act by an opera company.The changes in the new version of Fire were necessitated by the size of the opera house.

The version of Boris came about in small part due to censorship. Until 1872 Tsars were not allowed to be portrayed on the opera stage. This was changed to limit the exclusion to the Romanoff’s who came to power after Boris and remained in power until 1917. Demands that female characters be enlarged played a role. Mussorgsky did not have a problem making women more prominent in the opera. Beyond that, because Boris was such a grand subject, other composers attached themselves to improve the work. Rimsky-Korsakoff’s version is still produced. Dmitri Shostakovich tried his hand at improvement too.

Friends of Mussorgsky huddled around the composer suggesting changes to his 1869 creation. Mussorgsky thought they might be right in their criticism, and enriched the piece for its premiere four years later.

The 1869 original was performed the Met with the world’s leading performer of the title character, Rene Pape. In one sense the prudction is small. The sets are suggestive rather than literal. Change of scenes happens with drops and lighting.

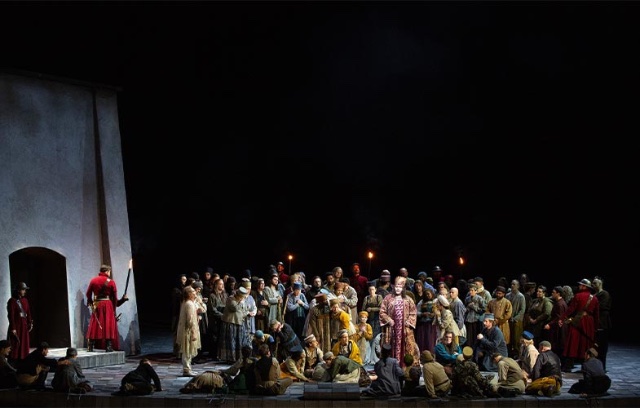

Yet this Boris is also large. This story of the Russian people, boyars and serfs, and their the Tsars is filled with a sense of the people. Who could better fill a stage and give it grandeur than the Met chorus? They are a magnificent presence throughout.

Stephen Wadsworth was responsible for the 2010 version of the opera, a more expansive, less stark version. Wadsworth always perfectly captures the Russian mood—set by characteristic folk music, the Volga boat song and aching melodies in minor, which suggests the yearning of a people for peace and prosperity.

Godunov is a complex figure. A beneficent ruler, he makes sure starving Russians are fed. He is plagued by the notion that he murdered the rightful heir to the throne. (In history, he did not. In the Pushkin drama which Mussorgsky used for his libretto, he did.) Angst is a Russian specialty that works well in the opera.

The Met chose to offer the seven scenes one after another without interruption, a two hour and twenty-five minute performance that satisfied. Whether their decision to mount this version was dictated in part by concerns that an agreement would not be reached with the stage hands’ union (one of the last holdouts in the Covid quarrels of the unions with the Met). It was a wonderful opportunity to see the original work of the composer. While it is not a complex as later versions, this version is powerful and its musical storytelling, original. Mussorgsky’s imagination and his ability to depict emotion in harmonies is clear.

The cast, in addition to Pape, whose performance in this role is for the ages, was to a one first rate. The simplicity of the sets brought forward the performances and the music. Glued to our seats, undistracted by intermissions, we are swept up in a tale too often told the world over, but with particular severity and cruelty in Russia: the grasp for power by rulers at the expense of the ruled.

Some of the audience wondered what had happened to the Polish scene. Well, Mussorgsky had not written it yet. For all the jockeying for position in the editing of of the opera by leading Russian composers, the sheer brilliance of Mussorgsky is especially evident in this version for which he alone is responsible.

Will we be able one day to return to the original version Terrence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones?