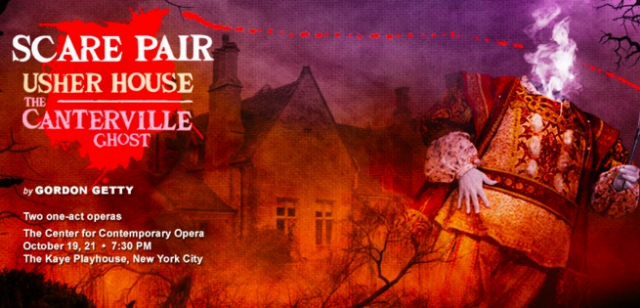

Gordon Getty Unearths Ghosts

A Pair of Seasonal Operas

By: Susan Hall - Oct 20, 2017

The Center for Contemporary Opera is presenting the premier of a pair of operas by Gordon Getty. Usher House is based on Edgar Allan Poe’s The House of Usher. The Canterville Ghost interprets Oscar Wilde’s sympathetic take on a ghost who cannot die, a sort of Emilia Marti from the Makropulos Case. Marti has lived 337 years when we meet her. Enough is enough, she declares in Czech. The Ghost shares this sentiment.

Getty speaks about his work with fluttering fingers raised high above his head. He assumes the ghost role with ease. His music clearly comes both from the heart and his inner ghost. He cautions fellow composers to be true to themselves, and clearly he is. A delightful man, full of good humor, his spirit seems to contradict traditional opera where bad people do awful things. You can’t imagine Getty creating an ugly Scarpia, Fafner or the Devil for that matter.

Yet, as the scrim rises on The House of Usher, the transparent music that accompanies the singers is by no means sweet. Getty, who had aspirations to be a singer, clearly sympathizes with the range and textures of the human voice. He is fortunate in the principals in this opera. Dominic Armstrong, a tenor, sings Edgar Allan Poe in querulous and increasingly fearful tones as he watches the story he will then write unfold.

Getty points out that there is almost no dialogue in the Poe story, and he has taken liberties that fit well. One visually helpful choice was to have Madeline, who is dead, sing as an offstage voice. Summer Hassan created a rich sound presence to accompany Jamielyn Walsh who danced the silent role on stage. She at first appears like a floppy Raggedy Ann, propped up by Dr. Primus, seemingly in death throes. She returns to float eerily about the crypt, threatening the sanity of all who watch. The orchestra bursts forth from their transparent vocal support role as she dances, demonstrating Getty’s mastery of a fuller form.

Roderick her brother is sympathetic in his confusion. Keith Phares is dashing in the role, and his baritone contrasts well with Armstrong’s as they wend their way to disaster.

The direction by Brian Staufenbiel keeps the action moving forward. Sets by Dave Dunning are extraordinarily apt. When the scene opens, we see only darkness, with glimmering shadows. As the orchestra begins to play, Poe is seated center stage on the steps of Usher House, behind the scrim, which lifts as he enters the crypt of the house. Within the house, lighting by Nicole Pearce helps distinguish a library full of dark secrets and a portrait hanging at a distance which shows brother and sister, Roderick and Madeline, as young people. The crypt's arches recede back.

An ominous overtone hangs in the air. Synthetic growls underpin the orchestration. Chimes which herald Madeline are lovely coming from a percussion section set way back under the stage. The orchestra is larger than the pit in the Danny Kaye theater. They were superb under Sara Jobin.

The Canterville Ghost is a funny take on a Ghost who can’t die. His blood keeps erupting on an armored statue where he lives. He was chained decades ago and desired death eludes him. Matthew Burns growls in his bass, wishing that release from his immortal coils was near. Virginia, sung in a big, yet delicate voice by Summer Hassan, can provide this. Getty takes joy in not letting us know exactly how she accomplishes his demise. This tease keeps us wondering.

Again the set it effective. A four-tiered home allows the action to move from sitting room, to upper hallway, to bedroom and back down to the dining room. The twin boys of the house are impish and tear around the stage, terrifying the ghost. Other-worldly projections by David Murakami suggest an after world in the walls of the house.

Getty's work is well-crafted. What is most striking is how well it sits in the voice and what a good dramatist he is. The pleasure that he clearly takes in his work is infectious.