Todd Haynes Documentary Evokes The Velvet Underground

Is There More to the Story of Lou Reed and His Band

By: Steve Nelson - Oct 21, 2021

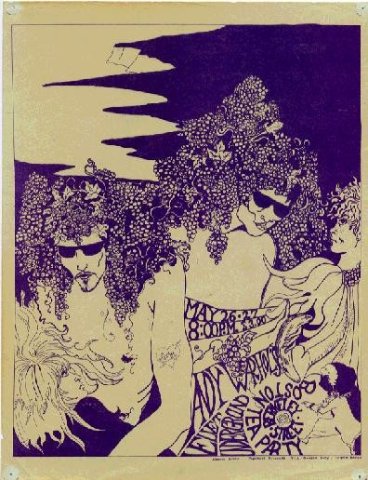

I’ve been waiting over 51 years to see this documentary, since the last time I saw The Velvet Underground play. It was June 24, 1970, their opening night of a two-week gig at Max’s Kansas City, after not doing a show in New York for over three years. I’d designed the poster promoting it, mimicking the look of an ad in a New York subway car. I was there with my girlfriend Jan. Todd Haynes could not be there. He was only 9 years old.

The first time I’d seen the Velvets was on April 28, 1966, at a benefit party for the Paris Review at the Village Gate nightclub in New York. It attracted about a thousand of the city’s literati and glitterati (I was just a law student who came down from Cambridge for the night). Few of them would have known who The Velvet Underground were, except perhaps for their association with Andy Warhol.

I didn’t either, but as a longtime avid rock ‘n’ roll fan I was blown away dancing with my then girlfriend Beth to the powerful, pulsating, hypnotic sound of the band, accentuated by strobe lights. At one point I saw Frank Sinatra coming down the stairs to where the band was playing. He took one look and, recoiling in horror at what he beheld and the assault on his ears, went back upstairs. Beth and I kept dancing to rock ‘n’ roll unlike anything I’d ever heard. I couldn’t get their sound out of my head for months.

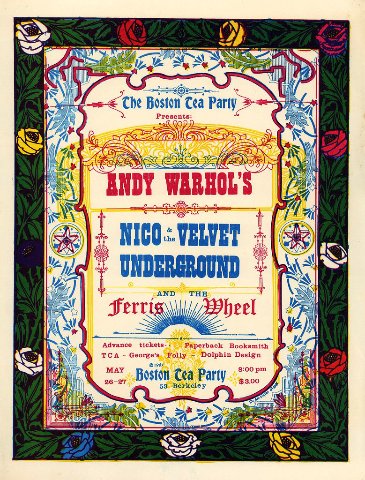

The next time I saw the Velvets play was on May 27, 1967 at a psychedelic music hall called The Boston Tea Party. What brought me there was a long story, as told in my memoir Gettin’ Home: An Odyssey Through The ‘60s. I’d been listening to their new album incessantly, the one that Andy had designed with the peelable banana on the front. It turned out to be a critical gig for them, because they came to Boston having just severed their ties with Warhol and his multimedia extravaganza the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, in which they had performed.

In a strange twist of fate, by the end of that summer I had become the manager of the Tea Party, despite having no experience in the music business. But when it came to booking bands, I knew what I liked and what my hip friends around Harvard Square were listening to. I liked The Velvet Underground. A lot. So I booked them a lot, because I could. Over nearly three years I presented them in seventeen shows at the Tea Party and in venues in western Massachusetts, and got to know the band musically and personally.

Who didn’t like them a lot was the great concert producer Bill Graham. After they played at his Fillmore Auditorium in May 1966, he vowed never to book them again, and didn’t. They were widely panned in the mainstream press. “Very Greenwich Village sick…pretty lame” (The San Francisco Chronicle, after their Fillmore gig). “A short-lived torture of cacophony” (The New York Times, quoting the chairman of a convention of psychiatrists where they performed).

The record-buying public was largely indifferent to their four albums, which barely cracked the Billboard sales charts. But their performances and records were reaching a small but important audience: the musicians whom they inspired. The underground and music press also was taking notice of the Velvets: “Consistent and almost easy brilliance” (Fusion). Ultimately, they came to be recognized as “the most influential American rock band of all time” (Rolling Stone).

So it’s been with great anticipation that I’ve awaited the Todd Haynes film, his first-ever documentary. There had been an obscure documentary in 2006 called The Velvet Underground -- Under Review, by an English production company Chrome Dreams which did a number of such films, like The Who – Under Review. I appeared in that VU film and, as a professional video producer in my own right, did a lengthy interview for the film with their drummer Moe Tucker in the kitchen of her home in south Georgia.

Now, however, The Velvet Underground story would be in the hands of a creative filmmaker like Todd, whose documentary would certainly get wide distribution and attention. (Disclosure: I was an Archival Consultant to the film and provided photos of the Velvets by my old friend Henri ter Hall, promotion posters I’d done and video I shot at a show in 1970). Its release was frustratingly delayed by the pandemic, but I knew the VU would soon get its due. And they do.

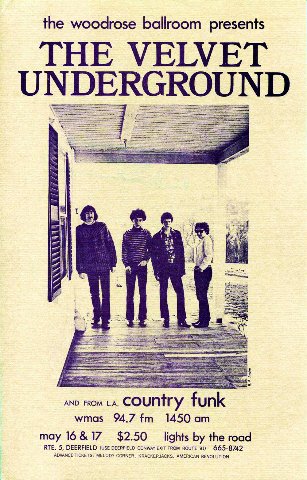

I was invited to the screening and reception at the New York Film Festival, but being immunocompromised was unwilling to sit in a theater sure to be packed. Instead, I was going to stream it on my computer, which is how I watch everything, but decided to check online where it might be playing locally. It was at the Amherst Cinema, just 12 miles from the former site of The Woodrose Ballroom, a club I owned where the Velvets played ten times in 1969. It was the perfect place for me to see the film, early on a sunny Sunday when I knew it would not be crowded. It was my first time in a movie theater since the pandemic began. I had to go.

Todd faced a real challenge in making “The Velvet Underground.” Unlike the typical rock doc, with lots of footage of a band performing and recording, there was precious little for a group that was obscure during its existence of less than five years. But Todd made the most of what he had to work with, including hours of various visuals he licensed, and turned it into a strength of his film. Inspired by Warhol’s multimedia EPI, he used split-screens and fast-cut layered imagery to evoke the feeling of the Velvets and the creative milieu from which they emerged.

Those split-screens include the so-called “screen tests” which Andy shot at his “Factory” of Lou Reed, John Cale and others who appear in the film. Lou stares at you silently and almost unblinking while the Velvets story unspools in the adjacent images and sound. Of course, having passed away in 2013, well before production of the film began, Lou is only heard from in voice-over. But John is on camera as a talking head with plenty to say about the band. He recalls how he came to the U.S. from Wales with a fellowship at Tanglewood sponsored by Leonard Bernstein, where he shocked the widow of legendary Boston Symphony Orchestra conductor Serge Koussevitzky by taking an axe to a piano during a recital.

It was a different axe, an electric bass, which he used to join up with Lou Reed. John had been part of a downtown avant-garde music scene, well documented in the film, experimenting with the sound of drones. He says they tuned to the 60-cycle electric hum of a refrigerator and calls it “the drone of western civilization.“ I found that comment particularly fascinating, having recently written a book on how electricity is driving human evolution, with a section on how music evolved from banging on rocks in the Stone Age to banging out rock in the Electric Age.

John brought the drone into The Velvet Underground with his electric viola, a big part of the band’s unique sound. Lou, Moe and guitarist Sterling Morrison brought the rock ‘n’ roll they grew up with. We hear the hauntingly beautiful doo-wop lament “The Wind” by The Diablos. Later we see footage of Bo Diddley playing his song “Roadrunner.” His music was heavily rhythmic, and Moe has often cited Bo as one of the main influences on her drumming. There’s a female guitar player in his band. So, why not a female drummer in the VU?

To some extent John’s predominant presence on screen and his eloquent insights make it John Cale’s film about The Velvet Underground, but he has plenty of company, including his bandmate and drummer Moe Tucker. She remarks that in performance her rock-solid beat enabled Lou and John to improvise. They could “go off into nowhere land and be playing who knows what” and then have a place to come back to. In light of revelations later in the film about the tensions between Lou and John that ultimately led to Cale’s departure, her steadying presence likely helped hold the band together, until it couldn’t.

In making the film, Todd decided only to interview people who were there at the time, almost all in New York, not the many people who never saw the VU but would have been happy to pontificate about the band. Some of the most interesting comments come from Lou’s sister Merrill about his childhood (she laughingly demonstrates “The Ostrich,” a dance tune by Lou and John’s pre-Velvets band The Primitives); Mary Woronov (a Factory girl infamous for doing the “whip dance” with Gerard Malanga in the EPI), and Danny Fields, a longtime friend of Lou and renowned rock publicist (he came up from New York to some of their shows at the Tea Party).

Most delightful was my old friend Jonathan Richman, leader of the VU-inspired, pre-punk, pre-New Wave, pre-indie band The Modern Lovers (with future Talking Head keyboardist Jerry Harrison and future Cars drummer David Robinson). A VU fan nonpareil, Jonathan not only talks the talk about the band but uses his guitar to back it up. He recalls how when the Velvets played Sister Ray at the Tea Party (it often went on for 20 minutes or more), they’d end the song so abruptly that the audience, dancing furiously, would stop dead in their tracks, stunned into silence for five seconds (he counts them down with his fingers) before applauding. “The Velvet Underground had hypnotized them one more time.”

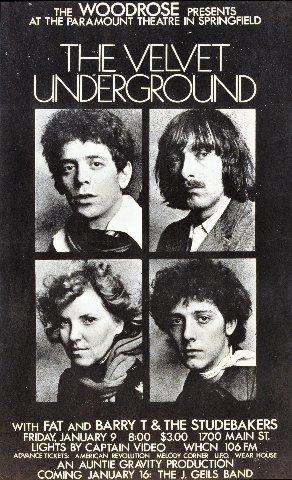

While everyone else was trying to understand the VU, only Jonathan could say that when he first heard them, he knew that “these people would understand me.” He talks about how nice they were to him and how Sterling taught him how to play the guitar. He mentions that they even let him open for them once. I remember that well, because it was at a show I produced at the Paramount Theater in Springfield, Mass. on January 9, 1970.

I was sitting in the balcony with Jan before the show. When we met a few weeks earlier we connected over having seen the early Velvets, she as a student at the University of Michigan at an EPI performance, me at the Village Gate. Oddly, her last name was Lewis (which is how Lou’s given name is spelled) and my given middle name was Reed. I guess we were fated to come together as VU fans for life.

As we were talking, Jonathan came over. I knew him well and was surprised he was there, but he never missed a chance to see the Velvets play. He’d gotten a ride out from Cambridge with Barry Tashian and Bill Briggs, who were opening that night as Barry T and the Studebakers. They were best known as the guitarist/singer and keyboardist for The Remains, a garage band legendary in Boston who’d opened for The Beatles on their last tour.

Jonathan wanted to let me know that Sterling told him it was OK to use his guitar and amp and do a few numbers. This was news to me, and as show producer I told him that nobody goes on without my say-so. But as a friend I quickly added that if it was OK with Sterl, it was OK with me. So he went out in front of a closed curtain and played, the audience puzzled by this unknown short-haired kid in a while vinyl jacket playing solo. Jonathan busked in Harvard Square, but this was his first plugged-in performance in an indoor venue.

The VU returned to the Paramount on April 17, direct from two days in the studio in the initial recording sessions for their fourth album Loaded. Moe was not with them, sick from being pregnant. They went on as a trio, with Doug sometimes playing drums. Using my friend Michael Pitkow’s video gear, a primitive Sony Portapak, I shot some grainy black-and-white footage Todd was able to use, with Doug singing “Candy Says.” Yet even in Moe’s absence, her beat was so ingrained in their playing, it was as if she were there, the phantom of the Paramount. That gig was the end of my career as a concert producer. I didn’t know at the time that it was the beginning of the end for The Velvet Underground.

Moe did play in a few more gigs, but by the time of the Max’s dates and more Loaded recording sessions, she says in the film that she was “too fat to reach the drums.” Their two-week gig became a summer-long last stand, before Lou quit. After the excitement of being with The Velvet Underground on screen for two hours, it was sad to see the band and the film come to an end. We do get a coda, a reunion of Lou, John and Nico in Paris in early 1972 from a French TV show, with Lou doing “Heroin” on acoustic guitar and John on viola. “All Tomorrow’s Parties” never sounded more mournful as the credits rolled and faded to black.

I’d recommend Todd’s film to anyone interested in The Velvet Underground and the era of creative ferment in the downtown New York music/film/art scene from which they emerged. Even with my deep history with the band, I saw images I’d never seen and learned things I never knew. His film is an immersive experience, like the EPI was, an Exploding Cinematic Inevitable. See it on a big screen if you can. But see it.

Todd chose to focus on the VU as the Lou Reed/John Cale band I think of as “The Downtown Underground,” and the creative world in New York. There is much less focus on them after the departure of Cale, who admits on camera that he never met Doug Yule, who joined the band after Lou forced John out. But I’d like to add to the Velvets story with more about the band I call “The Out-of-Town Underground,” beginning at the Tea Party at that May ’67 gig.

They’d fired Andy and the EPI was kaput, but Nico was still expected at the opening night on Friday. She didn’t turn up until the show was nearly over, and Lou wouldn’t let her onstage. He resented that Andy had foisted her on the band, and in the EPI her beauty stood out against the nondescript members of the band all dressed in black – she was the main visual attraction in the group. That night he was likely seething when he saw the Tea Party handbill promoting the show as “Andy Warhol’s Nico and the Velvet Underground,” giving her top billing.

When I came to the Saturday show, Nico was nowhere in sight. Even her name had been covered over on the remaining copies of the handbill. It was the first night of The Velvet Underground as a touring four-piece rock band playing venues that showcased the music of the ‘60s. They would not do a Velvets show in New York until that Max’s gig three years later.

Lou later spoke about that Tea Party gig in an on-air interview on the pioneering Boston FM stereo rock station, WBCN. “Well, you know Boston was the whole thing as far as we were concerned. It was the first time we played in public and didn’t have all those things thrown at us. You know, the leather freaks, druggies, the first time that anybody just listened to our music which blew our minds collectively” (from the film "WBCN and The American Revolution" and the book "WBCN and the American Revolution: How a Radio Station Defined Politics, Counterculture, and Rock and Roll" (MIT Press) by Bill Lichtenstein).

There was to be one more event with Warhol, minus the freaks and the EPI. The Tea Party management convinced Andy to come to the club in August and film the VU playing. “Be part of what’s happening… you are the star,” hyped the handbill. The promotion was a huge success, the place was packed with people seeking their 15 seconds of fame on camera. The film Andy shot was used extensively by Todd.

In the fall the band went off the road to record their second album, White Light/White Heat. If anything, it was more challenging than the banana album. Then in the spring they resumed a heavy schedule of gigs: Boston, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco and other points in between. But touring can take a heavy toll on a band and heighten existing tensions between its members.

After a weekend at the Tea Party in September, Lou laid down an ultimatum to Moe and Sterling: “You can either stay with him or go with John,” she recalls. Later she recorded the tune “I’m Sticking with You.” It might as well have been “I’m Sticking with Lou.” Despite a personality which could be off-putting even to those who knew Lou well, you see in the film that he and Moe were truly friends. Sterling stuck around too. Now the band was Lou’s VU.

Moe says that “Lou really wanted to get some success going… real success… he wanted to make it less avant-garde.” From the time he was a teenager, Lou wanted to be a rock star. In the song “I’m Set Free” on their third album (recorded not long after John’s forced exit), Lou sings of no longer being “bound to the memories of yesterday’s clowns,” John and Nico, and being “set free to find a new illusion,” success and stardom.

To fill out their lineup, the Velvets brought in Boston rocker Doug Yule, whom Jonathan calls “a very exacting and serious musician… with his own harmonic sense which brought something different.” Moe recognizes that “Doug had his own things to bring to the band” but says “no one could replace Cale.” Lou didn’t want to replace him, and didn’t have to. When they returned to the Tea Party on December 12 for their first gig there with Doug, they opened with “Heroin.” This was highly unusual; the only other time I’m aware that they opened with the song was eleven days earlier in Cleveland, another town they played often and where the audience knew their music well.

Lou typically began their shows with a simple introduction, “Good evening, we’re The Velvet Underground,” before launching into the first number. By opening with “Heroin,” it was as if he was saying, “We’re still The Velvet Underground, and if you don’t like it, go fuck yourself.” The Tea Party audience liked it. They always did. On stage that night Lou declared, “This is our favorite place to play in the whole country.”

In April 1969 they released that third album, called simply The Velvet Underground, as though it was the introductory offering from a new band, which in a sense they were. It was much lighter and gentler than their previous work. In the film Lou talks about wanting space in their music, unlike the dense cacophony of their previous work. You hear that new sound clearly in the ballad “Pale Blue Eyes” about adultery: “It was good what we did yesterday, and I’d do it once again.” Covered by the right artist, it could have been a hit on the country charts. The Velvets were “Beginning to See the Light.”

The band continued touring, the usual places plus some new ones, including The Woodrose Ballroom, in rural South Deerfield in western Massachusetts. It was a club I’d opened in an old roadhouse with my friend John Boyd from the Tea Party lightshow and his wife Barbara. You might think it strange for that ultimate New York band to be playing for hicks in the sticks, to borrow from a famous headline in Variety magazine. But the audiences liked them, and it gave the Velvets a chance to try out new material away from more critical ears. Anyhow, it was hard to still think of the “Out-Of-Town Underground” as a New York band, when they never played there and the Tea Party was in effect their home club. With the departure of John and the addition of Doug, all four members of the band had grown up in the suburbs of Long Island.

Their fourth album was intended to be “loaded” with hits, and despite Moe’s absence, had some classic Velvets tunes like “Sweet Jane” (“Me, I’m in a rock ‘n’ roll band”) and the autobiographical “Rock & Roll,” with Lou as the protagonist Jenny: “You know her life was saved by rock and roll.” It also included the tune “Train Round the Bend.” The band came up from New York for the Paramount Theater gig in January on the train, the station being near the theater. As the song chugs along, the train heading back to the city, Lou rues, “Been in the country oh, much too long, trying to be a farmer. But nothing that I planted ever seems to grow.” Success continued to elude him, and you could hear in his voice that he was weary.

The gig at Max’s became Lou’s last stand with The Velvet Underground, ending when he quit at the end of the summer, before Loaded was released. The band tried to carry on with Doug in the lead. The following winter Jan and I drove up to see them at an apres-ski bar in North Conway, New Hampshire called The Alpine. Doug brought in a terrific bass player, Walter Powers, whom I knew from his many performances at the Tea Party. But of course, this wasn’t the real thing, it was the Velvettes. Moe, who ordinarily didn’t drink, tried to cope with the weirdness of it all by belting back sombreros.

More than thirty years later my wife Jan and I went to see Lou and his band play at the Calvin Theater in Northampton, Mass., down the road a few miles from the old Woodrose. He left us tickets and backstage passes. It was great to hear him live again after so long. After the show I went backstage while Jan waited for me outside the theater – she didn’t like hanging around those scenes.

Lou greeted me and said he wanted his website to sell an official reprint I’d recently done of the Max’s poster. Afterwards, I told Jan what happened next, and in her understated way she just smiled and gave me a hug. Lou had introduced me to the members of his band and explained my connection to the Velvets. Then he said to them, “We couldn’t have survived without him.”

What can I say about the band that hasn’t already been said, long after they existed, and now is so well evoked in Todd’s film. In thinking about the two versions of the Underground, the “Downtown” and the “Out-Of-Town,” I have to ask this question: what if they had broken up when Lou wanted to split with John, and their legacy was just the first two albums and not many live performances? Would they still be “the most influential American rock band of all time”?

I think not. They would likely have been remembered only as a shocking experimental New York band with an electric viola who sang about sex, drugs and death, a meteor that flashed brilliantly but briefly from the Warhol constellation across the music sky. Their later recordings and performances when Lou was sole leader of the Velvets, and Doug brought a new musicality to the band, rounded out a remarkable body of work. It encompassed the obsessive rush of “Heroin” (“I’m going to try for the kingdom if I can”) with the band in full manic mode, to the quiet surrender of “Jesus” (“Help me find my proper place”) with minimal accompaniment. Two sides of the same Velvet coin which has inspired musicians and listeners alike. In the end they were not just art rockers from New York but a great rock ‘n’ roll band that got people dancing downtown at the EPI (even ballet legend Rudolf Nureyev!) and out-of-town at the BTP.

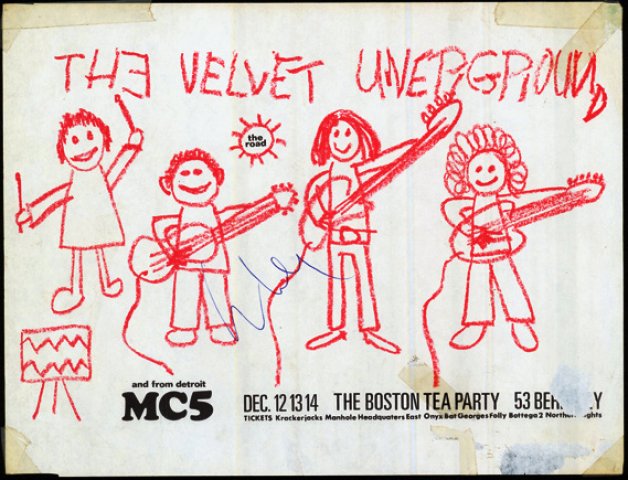

I’ll give Lou the last word. I designed the poster for that December 12th Tea Party show with Doug. I wanted to counter the prevailing dark image of The Velvet Underground because I didn’t think it truly reflected them. I’ll be your mirror. So I portrayed the band as kids crudely drawn in red crayon, their name misspelled, as though another kid (me?) had done the poster. They’re grinning and having fun playing rock ‘n’ roll. When I saw Lou offstage and showed it to him, he looked right at me and said with a slight smile, “How’d you know that’s who we really are?”