Ed Burns Nice Guy Johnny

Williamstown Film Festival: It’s a Wrap

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 26, 2010

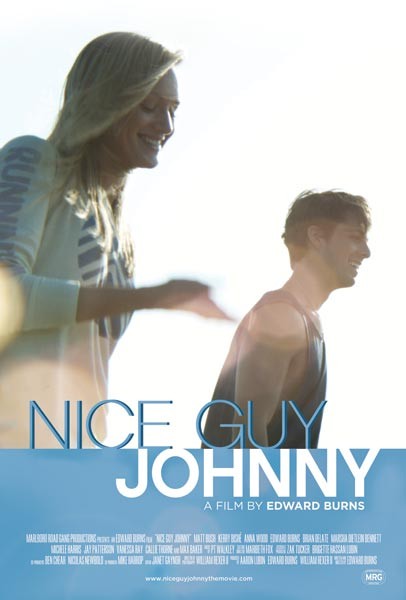

Nice Guy Johnny

Writer/ Director: Edward Burns

Producers: Aaron Lubin, William Rexer II

Co-Producer: Mike Harrop

Cast: Matt Bush (Johnny Rizzo), Kerry Bishe (Brooke), Edward Burns (Uncle Terry), Anna Wood (Claire), Max Baker (Max).

Running Time: 90 minutes

There were bagels and coffee in the lobby of Images Cinema for an 11 A.M. screening of Nice Guy Johnny by writer/ director Edward Burns. Yet again, we were greeted by the artistic director of Images, Sandra Thomas. The feature was preceded by a screening of the charming and compelling, 18 minute, God of Love, by writer/ director/ star: Luke Matheny. In a field of 24 short films, through exit polling, it won the annual Reeve Award.

The two week long Williamstown Film Festival is now a wrap. It means that artistic director, Steve Lawson, starts to get his life back. He announced that he won’t pick up the phone or answer e mail from now until.

The Burns film warmly conveys the dilemma of Nice Guy Johnny. At 25, Johnny Rizzo (Matt Bush) is engaged to Claire (Anna Wood) who is pressuring him to give up working for nothing as a radio sports commentator. Through her father, who is also paying the rent on their house, he flies to NY for a job interview with a better paying, cardboard box company. Claire won’t wait for her dream of security and starting a family. Even if it means ending Johnny’s dream of a life in sports journalism.

It is a conundrum that anyone with a life in the arts, or who has followed their dream, can readily identify with.

Johnny is, indeed, such a nice guy. He just wants to do the right thing and please everyone. That sets up Uncle Terry (Ed Burns) as too much of a one dimensional, philandering bastard, negative role model, and ersatz svengali. Terry, the perpetual adolescent, bar tends when not womanizing and taking advantage of well connected, married women. For Terry, life is a self indulgent, hedonistic scam.

But Terry is spot on in advising his nephew that 25 is way too young to pull the plug on career dreams and independence. Is Claire really worth it? Terry talks Johnny into a weekend in the Hamptons at “his” house. Well, “her’s” actually. It belongs to one of his mistresses.

In the confusion that ensues Johnny inadvertently meets a free spirit, unattached tennis pro. Brooke (Kerry Bishe) has given up a life on the circuit to bum about giving tennis lessons. Of course, as the plot unravels, she is just perfect for Johnny. We assume that they live happily ever after. Or at least long enough to roll the credits.

Which are not that long actually. This was one of the points of Larson’s discussion with co-producer Mike Harrop. The first film by writer/ director/ actor, Ed Burns, The Brothers McMullen (1995), was shot for $17,000 and went on to critical acclaim earning several million. It was that too rare, long shot winner that motivates every independent filmmaker.

Even with that big score, and a now established reputation as a bankable filmmaker, Harrop discussed how plans to shoot a film, at $1 to 1.5 million, fell through. There is a changed environment that has put a squeeze on independent filmmakers. Backers and producers are more sophisticated in demands for a return on their investment. In the current economy there is less available capital. Marketing and distribution strategies have changed dramatically. With more on line download options, and a lot of free internet content, there are new paradigms for how films get made, seen, and sold.

The new word is disintermediation. It describes eliminating the middle man and going directly to the consumer. The trend and related socio/economic shift cuts across all aspects of how we consume information, intellectual property, and artistic content. It is at the center of all aspects of communication. There has been the erosion and dismantling of giants in media/ publishing, the recording and film industries, network and cable television. While the landscape has changed, like a fundamental law of physics, matter cannot be created or destroyed. There is as much, if not more, content than ever. What has evolved and changed is how it is delivered.

Cutting across many art forms everyone is trying to figure out how to surf the next wave of technological development and trends of consumer culture. At the low end of the spectrum are bands, and small independent filmmakers, trying to circumvent (disintermediate) record companies and distributors. These are the traditional giants of the entertainment/ publishing/ media industry who reap the lion’s share of profits leaving the content providers/ artists with what is left.

Unless you are a famous and established artist, with a great team of management/ legal advice, most creators earn very little from the sales of their CDs, books, films, videos and product. The major artists front load profits through their initial contracts. How many independent creators have the resources to chase after an accurate accounting of actual sales? Even then, there are standard clauses of an average 10% margin of error. That obviates a breach of contract.

Small bands have found a way around record companies. They let fans download songs from their websites. Or pay for just the tracks consumers want. They build an audience base for their concerts. Similarly, authors can sell their books on demand. It’s expensive to print and ship just one book at a time, but more authors now publish their books. With so much content available, on demand, the middle man is shrinking.

During the post screening discussion with Mike Harrop we were astonished to learn that Nice Guy Johnny was shot in 12 days, over four months, for just $25,000. The assumption is that nobody got paid and that everyone involved is an “investor” in the project.

One might quibble about some of the production values but Nice Guy Johnny is a pretty remarkable film considering that it was created on vapors. Would throwing in a million or two have resulted in a better film? It is a tribute to Burns, and his collaborators, that they had the guts and vision to create their film.

With such miniscule production costs, arguably the film could have been financed with a credit card, Burns has opted to own and control his product. He has decided not to sell it or make a deal for distribution. Other than a very successful round of festivals, there is no theatrical release. It will be offered through I Tunes, this week, and become available as video on demand.

It is ever more difficult for audiences to find screenings of independent films. As Harrop commented, he tries to see indy films about once a week because, by next week, they just won’t be there. That’s New York. Here in the Berkshires it is even more difficult to find independent films and documentaries. Images, for example, has a single screen.

Of course, how do audiences know that films such as Nice Guy Johnny are available? Harrop commented that there is a small budget for marketing. Reviews from festival screenings help to get the word out. The hope is that an interesting film becomes viral as was the case with The Brothers McMullen. Like Nice Guy Johnny more and more artists are reluctant to give up on their dreams. For Burns, that means an end run around the studios. Many established actors and filmmakers balance a career with commercial work, and TV, while continuing to make small, well crafted films. As we saw during WFF actors take on these projects for their challenging roles. The hope is that it will lead to other opportunities.

The tough question is how to deliver product to the audience. It was the subject of a seminar luncheon at Orchards. The topic was “DIY! The Bow Shock of Indie’s Future.” The speaker was Jeffrey Brandstetter an entertainment attorney, and CEO, of the online distribution platform, IndiePlaya.

In the established mode of doing business he described a process in which independent filmmakers basically lose rights to their films. The distributor controls all aspects of theatrical release, promotion, and marketing. After an initial, limited release a film often languishes. If a distributor does not push the film it is under contract, and cannot be moved, or sold to another distributor. Brandstetter described scenarios where, even if the distributor goes out of business, it continues to control the film. The distributor controls the marketing, and like all other expenses, this is deducted from the “profits.”

Under the business plan for IndiePlaya there are no up-front fees, contracts, or royalties. For each transaction the company takes $1.29. The filmmaker gets the difference, be it from a $2.00 rental, or purchase of a DVD. There is also an ability to analyze how the product is consumed. This can be tracked by the company, for a fee, but there are tools available for do it yourself tracking.

Significantly, Brandtsetter assured that there are enough levels of safeguards that pirates cannot steal content that is streamed. There is security for the artist’s intellectual property.

When asked about the limited availability of screenings of independent films in the Berkshires he had an interesting response. What if, in addition to films in current release, Images, or comparable art houses, had access to vast digital libraries? As we have seen through the success of the Met Live in HD there is an enormous audience for unique content. There is a significant cost reduction if small theatres switch from film to downloads or DVD.

Brandstetter suggested film clubs might rent theatres for weekly screenings. The members would get to select the content from the catalogue of distributors. Or, in an example like Nice Guy Johnny, directly from the filmmaker. For a fee. Also, by taking theatrical release out of the loop Burns, and other filmmakers, shoot with digital equipment and editing. Not shooting film is an enormous savings. Since the films are seen in art cinemas, and end up as downloads or DVD’s, there is little discernible difference between film and digital.

Even DVD’s like CD’s are being phased out. Netflicks now does the majority of its business through downloads. For a monthly fee the consumer has an almost limitless access to content. By making the move, first to direct mailing with no late fees, and then to downloads, Netflicks obliterated Blockbuster.

There is a paradigm, particularly with young audiences, that content is free. It has resulted in enormous internet presence. In this climate it is ever more difficult for the content provider to get paid for intellectual property. We have seen the negative impact on print journalism and network broadcasting.

The Boston Globe, following the lead of the Wall Street Journal, has announced that it will sell subscriptions to its on line edition. Shortly after that announcement, the Berkshire Eagle made a similar move. Networks that want to collect fees from cable companies are cutting back, or eliminating, on line content. It was originally thought that Hulu and other platforms would generate significant advertising revenue. That has not worked out.

There has been a lot of discussion of “pulling the plug” on cable fees. If you can get the content on line why subscribe? It is rather like when many consumers gave up on their landlines.

For print publishers, and networks, the risk is that consumers will simply migrate to ever expanding media and entertainment resources. As my journalist friend points out that means a lot of raw material, with no fact checking, or editorial supervision. That opens the floodgates for misinformation and its corollary in the rise of demagoguery. There is abundant evidence of that dangerous trend in the current elections. A strong, independent, and solvent media is a corner stone of democracy. So there is a lot more involved here than just getting paid for intellectual property.

It was a beautiful fall day when we emerged from the last WFF screening. There was a spontaneous gathering on the sidewalk of Williamstown. There had been such a rich menu of films and buzz about ideas. It resulted in lively and spontaneous debate.

Joe Finnegan, who chairs the WFF board, asked if the lack of a theatrical release for a film, like Nice Guy Johnny, means that it will not be eligible for awards? How does that lack of peer recognition impact the potential for getting the word out? Brandstetter responded with the industry term “Laurels” which is how many independent films find their audience. When Burns gets interviewed, as an actor, he gets to turn the dialogue to these smaller projects. There are many new strategies for promoting niche content.

During its two week, annual run WFF delivered a superb program of features and a cornucopia of short films. Through the lively post screening discussions, and seminars, we have a lot to absorb and think about. Until next year.