50 Years and Forward: British Prints and Drawings Acquisitions

Clark Art Institute

By: Clark - Oct 26, 2023

50 Years and Forward: British Prints and Drawings Acquisitions opens on November 18, 2023

(Williamstown, Massachusetts)— In celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of its Manton Research Center, the Clark Art Institute presents a richly varied selection of British works on paper acquired over the last fifty years. 50 Years and Forward: British Prints and Drawings Acquisitions opens on November 18, 2023 and is on view through February 11, 2024 in the Eugene V. Thaw Gallery, located in the Manton Research Center.

“The Manton Research Center is the home of our works on paper collection and its fiftieth anniversary commemoration provides us with a wonderful opportunity to showcase the exceptional British prints and drawings that are a part of this collection,” said Olivier Meslay, Hardymon Director of the Clark. “We are indebted to the Manton Foundation for the exceptional generosity of the gift they presented to us in 2007 that greatly enhanced our British holdings, endowed a gallery dedicated to British art, and created our Works on Paper Study Center.”

“As a complement to the British paintings that are always on view in the Manton Gallery, it is very special to be able to exhibit such a wide selection of our British works on paper,” said Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs. “The collection assembled by Sir Edwin and Lady Manton, and given to the museum in 2007, at one stroke established the Clark as a necessary stop for anyone interested in British art. The range and quality of the Manton drawings and prints have set a high bar for the acquisitions we continue to make in this area, and it is wonderfully exciting to be able to share many of these works for the first time.”

A companion exhibition, 50 Years and Forward: Works on Paper Acquisitions, opens December 16, 2023 in the Clark Center with a wide selection of prints, drawings, and photographs acquired between 1973 and 2023. Along with familiar works by Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528), Francisco Goya (Spanish, 1746–1828), Édouard Manet (French, 1832–1883), and Mary Cassatt (American (Active in France), 1844–1926), the exhibition highlights lesser-known parts of the collection, including early twentieth-century art, photographs by Berenice Abbott (American, 1898–1991) and Doris Ulmann (American, 1882–1934), and important images of and by Black Americans.

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

For museum founders Sterling and Francine Clark, works by artists from the British Isles did not constitute a major collecting focus. British art was largely eclipsed by the French Impressionist, American, and early modern paintings that became central to the museum’s identity. The emergence of British art as a significant collecting area is a recent phenomenon that was made possible by a transformative gift from Sir Edwin and Lady Manton’s collection of British art, donated by the Manton Art Foundation in 2007. British art soared dramatically in significance and visibility at the Clark, and a dedicated gallery created as a result of that gift allows works from the Manton Collection, mostly paintings, to be on permanent display. The light-sensitive works on paper, such as prints and drawings, can be on view only for short intervals, therefore, this exhibition is a rare opportunity to present the broad scope of the Clark’s British collection.

Highlights of 50 Years and Forward: British Prints and Drawings Acquisitions include lively figure drawings by Thomas Rowlandson (English, 1756–1827); vibrant watercolor landscapes by James Mallord William (J. M. W.) Turner (English, 1775–1851), Thomas Girtin (English, 1775–1802), and Hugh William Williams (Scottish, 1773–1829); heartfelt interpretations of nature by John Constable (English, 1776–1837), and Samuel Palmer (English, 1805–1881); vivid portrait heads by Thomas Frye (Irish, 1710–1762) and Evelyn de Morgan (English, 1855–1919); and an astonishing watercolor interior by Anna Alma-Tadema (British, born Belgium, 1867–1943). This abundant display showcases how the Clark continues, in the wake of the Manton gift, to enrich the British works on paper collection—ensuring that it grows in strength and variety far into the future.

50 Years and Forward: British Prints and Drawings Acquisitions is organized by the Clark Art Institute and curated by Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

A FOCUS ON FIGURES

The Manton gift that established British art as a major component of the Clark collection is known for its landscape focus, but it also contains significant figural works. Among these are seventeen of Thomas Rowlandson’s celebrated scenes of everyday drama, which often abound in humorous characters and gentle satire. The Clark’s collection of British art likewise includes academic figure studies, a compositional study for a scene from Shakespeare, and strong examples of mezzotint portraiture, a tonal method of making printed likenesses that reached its technical zenith as well as its height of fashionability in Britain in the late eighteenth century.

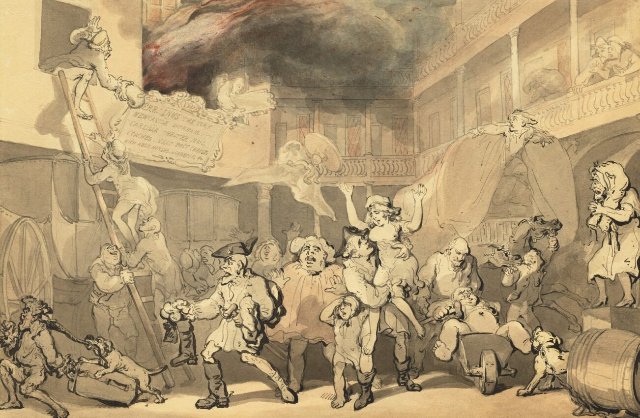

While Rowlandson’s Peregrine Rescuing Emilia from the Inn Fire (c. 1786) has origins in fiction (Tobias Smollett’s Adventures of Peregrine Pickle, first published in 1751), inn fires were also a fact of eighteenth-century travel. Inns were most often wooden structures quite susceptible to catching fire. In this depiction, an essentially terrifying situation—signaled by the billowing smoke and flames—is milked for comic effect through the reactions of figures in various states of distress, disarray, and undress.

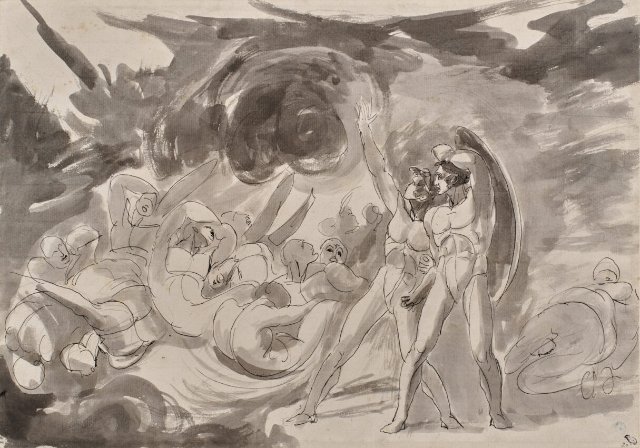

As the official portrait and history painter to Queen Victoria, George Hayter (English, 1792–1871) witnessed many of the goings-on at court, which makes plausible the connection of his drawing to a performance of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar given at Windsor Castle in February 1850. In Hayter’s drawing Scene from Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar”: The Ghost of Caesar Appears to Brutus (c. 1850) the seated Brutus appears to startle at the sight of Caesar’s ghost, his hand perhaps reaching for the sword behind him.

Sir Edward John Poynter (English, 1836–1919) was serving as the first Slade professor, an eminent teaching position in art and art history, at University College London and held leading roles in several of London’s most exalted arts institutions when he made the drawing Studies of a Seated Male Nude (1874). His reputation as an artist rested on large-scale historical paintings in the academic style, but he also excelled as a draughtsman, as seen in this carefully worked figure study. A notable painted example by Poynter in the Clark collection is the fallboard on the piano designed by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (British, born Netherlands,1836–1912), on view in the Museum Building.

Thomas Frye’s image of a man in eastern garb, Man Wearing a Turban and Leaning on a Book (1760), lies somewhere between portraiture—the artist may have used his own face as a model—and imaginative invention. Looking out at the viewer with a melancholic gaze, the young man holds a copy of an ornate book and is clothed in a patterned turban and a fur cloak suggesting Frye’s interest in texture and refined detail. In 1737, Frye began experimenting with mezzotint, a tonal method of printmaking, originally as a means of replicating his painted portraits. He then went on to produce original designs for mezzotint, not reproductions of his paintings or of other works of art, which was considered unusual for the time. This is the eighth in a series of life-size heads that Frye published in 1760. .

EXCEPTIONAL WATERCOLORS

The name of J.M.W. Turner is synonymous with the golden age of British watercolor, a period extending roughly from the mid-eighteenth to mid-nineteenth century. The Manton gift is rich in examples by Turner, Girtin, Constable, and Williams, all of whom were close contemporaries. They embraced the painterly style of watercolor rather than producing merely “tinted drawings” in the manner of earlier artists such as Rowlandson. The landscape views displayed in the exhibition, even if they remain (for the most part) based on identifiable sites, at times exceed their topographical or documentary intent with a deeply felt aesthetic and emotional engagement that is conveyed to the viewer through layered washes of color.

When Turner executed the watercolor View of La Riccia (Ariccia) (1817) as an illustration to James Hakewill’s publication A Picturesque Tour of Italy (1818–1820), he had not yet been to Italy. Instead, he relied on the architect Hakewill’s own drawings, made on site with the aid of a camera obscura, a darkened box through which a landscape view could be projected through a pinhole. Turner’s interpretations in watercolor greatly enhanced the qualities of light and atmosphere that made Italy such a desirable travel destination. He went there for the first time in the summer of 1819, a trip long delayed by the Napoleonic Wars.

In the early 1790s, Girtin and Turner exerted a mutual influence on each other while working closely together. An exceptionally well-preserved example of Girtin’s early topographical work, Windsor Castle (c. 1792), depicts the Round Tower of Windsor Castle as seen from the west. There is an almost identical view by Turner of the Tower of London from the same date. Around 1794, Dr. Thomas Monro, who was physician to King George III, as well as a collector and amateur artist, began inviting young painters for evening classes, at which they would sit two to a desk and copy drawings for pay by more senior artists. Turner and Girtin, who shared a desk, collaborated on Mountainous Landscape with Overshot Mill and Bridge (c. 1795) and other views thought to be after the artist Edward Dayes (English, 1763–1804). It is believed that Girtin did the pencil outlines and Turner filled in the washes. The landscape is probably from north Wales, rendered in delicate monochrome according to Dr. Monro’s taste.

A friend of Turner, Williams was born in England but lived in Scotland for all his adult life. As one of the few Scottish watercolorists to find a market for his work in London, Williams opened new travel horizons for early nineteenth-century tourists with his richly colored scenes of Highland landscapes and castle ruins, including Carne River from Loudoun Castle, Ayrshire (1804) and Castle Campbell, Clackmannanshire (1813).

A LOVE FOR LANDSCAPES

Despite watercolor’s recognized status as a fashionable and preferred technique for rendering landscape, monochrome landscape also thrived in the hands of British artists such as Constable, Edward Calvert (English, 1799–1883), and Palmer. Whether working in the medium of drawing or printmaking, these artists used limited means to evoke the distinct features and ephemeral phenomena of nature. Sir Edwin Manton (1909–2005) found a special solace in the landscapes of Constable, having been born in the same region, Essex County, in the east of England, and finding a nostalgic affinity for scenes of the English countryside after moving to the American city of New York at the age of eighteen.

Beginning in the autumn of 1805, Constable launched an intensive period of experimentation in watercolor, a medium in which he then felt more at ease than with oil painting. Following the precepts of an Oxford drawing teacher, Constable renders landscape elements as geometric rather than organically developing forms in Dedham Vale (1805). The trees are oval, rounded masses, with flecks of branches and foliage added afterwards. Other Constable works on view include Bow Fell and Langdale Pikes (1806) and Maudlin, near Chichester (1835).

In the late 1820s and 1830s, Calvert met regularly at Palmer’s home with a group of artists called the Ancients, who were strongly influenced by the visionary poet William Blake (English, 1757–1827). During that period, Calvert produced exquisite, minutely scaled wood engravings that are now considered his finest work. Shared only with a small circle of friends, the prints did not become commercially available until his son published them ten years after Calvert’s death. In 1850 at the age of forty-five, Palmer tried etching for the first time and, on the strength of his work The Willow (1850), gained election in that same year to the Etching Club, an artists’ society in London. Adding to the compositional interest of the tree overhanging a brook are a swan, cattle, and a distant tower in the landscape. In contrast to Palmer’s intimate etchings, The Setting Sun (c. 1862) is an ambitiously scaled watercolor. It was clearly intended as a visionary exhibition piece, one in which the artist would deploy all the tools at his disposal to create a glorious hymn to nature. The full poetic beauty of Palmer’s mature landscapes is shot through with a dazzling manipulation of light effects enhanced using shell gold. With boldly applied colors and scraped-away highlights, Palmer brings together the human, animal, and vegetal worlds into pastoral harmony under the beneficent sign of a brilliant sunset.

OF AND BY WOMEN

Over the nineteenth century, opportunities in Britain for women to receive art training slowly increased, though they still lagged behind the standard of that offered to men. While some women artists continued to learn their craft at home, others studied at art academies such as the forward-thinking Slade School of Art, which gave women access to live models from the school’s founding in the early 1870s—well before the Royal Academy followed suit. At the same time, modes of depicting women were undergoing a rapid flux. Even as male painters from the last third of the century cultivated a retrograde or otherworldly image of woman—idealized, abstract, and somewhat fragile—women artists countered these tropes with portrayals that asserted female strength, independence, and modernity.

By the time William Blake Richmond (English, 1842–1921) entered the Royal Academy schools at age fourteen, he had already met William Morris (English, 1834–1896) and Edward Burne-Jones (English, 1833–1898) on a visit to his elder brother at Oxford. In Portrait Study of a Woman (1860), the androgynous features and cascading ringlets are characteristic of Pre-Raphaelite style. With an inclined head and a fixed gaze, the model appears to bend forward, and her head and bare shoulder are rendered in boldly delineated contours and delicate hatched lines. The regal figure in Burne-Jones’s Study for Chaucer’s Dream of Fair Women (c. 1865) hews closely to the artist’s idealized and abstracted representations of women, influenced by Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (English, 1828–1882) and John Ruskin (English, 1819–1900).

Anna Alma-Tadema, the younger daughter of artist Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, portrays the interior of a building that served as her father’s studio in St. John’s Wood, London in a richly detailed watercolor, The Garden Studio (1886–87). The entry gallery depicted connects the studio portion of the building to the garden. The decoration expresses the family’s eclectic taste: in the corner by the door is a herm (pillar sculpture) of Sir Lawrence graced by a laurel wreath; at top center is a Dutch early modern portrait; and casually placed on a sturdy bamboo bench are pillows covered with seventeenth-century Flemish tapestries. Among more than 270 watercolors displayed at London’s Royal Academy in 1887, The Garden Studio was singled out by the Magazine of Art’s critic as “the best watercolor in the exhibition.”

A prolific and successful artist, Evelyn de Morgan was one of the first three women to enroll at the Slade School of Art. Head of a Woman is one of a group of drawings executed circa 1875, when De Morgan was around twenty years old and a pupil at the Slade. In this example, the set of the profile, direct gaze, and decided expression contribute to an image of a modern woman—strong, athletic, and self-assured—quite at odds with the wan and dreamlike women depicted by male pre-Raphaelite artists such as Burne-Jones and Rossetti during this same period. Also included in the exhibition is de Morgan’s Head of Medea (c. 1889). Executed in black chalk with gold-paint highlights, this preparatory drawing powerfully conveys the heroine’s complex psychology as she contemplates her murderous plan of revenge. The painting Medea was exhibited at the New Gallery in 1890.

RELATED EVENTS

Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, delivers a free lecture on the two exhibitions, 50 Years and Forward: British Prints and Drawings Acquisitions and 50 Years and Forward: Works on Paper Acquisitions on Saturday, December 16 at 1 pm in the Clark’s auditorium, located in the Manton Research Center.

A full slate of public programs is available at clarkart.edu/events.