A Man Called Ove: Grace of Community

Film by Swedish Director Hannes Holm

By: Nancy S. Kempf - Oct 28, 2016

"Men are what they are because of what they do, not what they say."

? Fredrik Backman, "A Man Called Ove"

There is an episode of the brilliant television series "Northern Exposure" called "Our Tribe" in which tribal elder Gloria Noanuk invites Dr. Joel Fleischman to be adopted by her tribe. Joel engages Ed Chigliak, his Tlingits friend, to try to get his head around this concept.

JOEL: Ed, let me ask you something. What does belonging to your own tribe mean to you?

ED: Well, I was raised by the tribe, but since I didn't have parents, I was passed around a lot. I never really thought about it. I mean, belonging to a tribe.

JOEL: I belong to the Jewish tribe, so to speak, but I'm also an American, you know? What does that mean? I mean, is there an American tribe? More like a zillion special interest groups. In my own case, I am a New Yorker. I am a Republican, a Knicks fan. Maybe we've outgrown tribes, you know? The global village thing. It's telephones, faxes, CNN. I mean, basically, we all belong to the same tribe.

ED: That's true. But you can't hang out with five billion people.

Swedish director Hannes Holm’s "A Man Called Ove" is a variation on this theme of community. What is community and how do we create it and then maintain it over time? How is the intimate community of marriage interwoven with the community of neighbors and friends? How do the interactions of the workplace sustain or betray community?

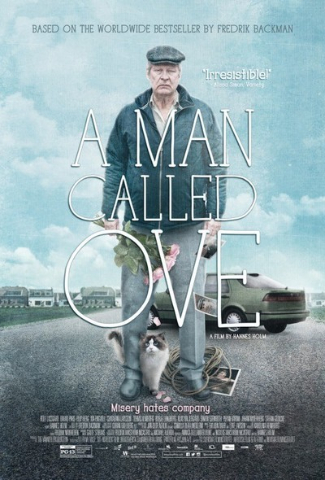

Adapted from Frederik Backman's 2012 novel and a 2017 Academy Awards selection for Best Foreign Language Film, "A Man Called Ove" is a moving portrait of a man whose suppressed emotion manifests in curmudgeonly bluster. Ove, realized in all his complexity by Rolf Lassgård and equally incarnated as a young man by Filip Berg, is the very definition of a wet blanket, yet from the time we meet him, we also see a widower whose well of grief is so deep it refuses to abate with time.

Ove lives in a townhouse neighborhood for which he and his neighbor and friend Rune – now the victim of the dual ignominies of a stroke and "the system" – spent much of their middle years structuring the rules and regulations. The erstwhile civic leaders of the self-governing community were pushed aside in what Ove insists was a "coup," and now Ove can only hold fast to his self-appointed morning ambulatory rounds, checking gates and locks and patrolling neighborhood menaces like a woman’s Chihuahua who pees on the sidewalk, an itinerant cat and a teen’s mis-parked bicycle.

After his morning routine, Ove heads to his job of 30+ years (we will learn he's an engineer) only to be called in by management to be made redundant, as the British say. The pair of millennial middle managers offer retraining in some sort of digital regimen, but Ove has a better solution, which is to walk out. After visiting his wife's grave, which he tries to do daily, he returns to his neighborhood home to regroup. When……into his enclave come the pregnant Parvaneh (Bahar Pars), an Iranian immigrant, her husband Patrick Lufsen (Tobias Almborg) and Parvaneh’s daughters Sepideh and Nasanin (Nelly Jamarani and Zozan Akgün). On day one Patrick backs his moving trailer into Ove's mailbox as Ove yells at him to watch out. Yet, in his fit of pique, Ove pulls Patrick out of the car, takes the wheel and expertly backs the trailer up to his new neighbor's front door. This seesawing behavior, the good deed exercised in the midst of ire, we come to understand as one hallmark of Ove's character.

Another is his desire to join Sonja, his dearly beloved, and to that end, Ove makes one interrupted or otherwise failed suicide attempt after another – each serving to ease him into a reverie of remembrance of things past. We learn first of his childhood and the loss of his mother, then of his coming of age with a loving but emotionally distant father, the events that compel him to make his way in the world alone, and his encounter with the woman who will be the love of his life – his Sonja (Ida Engvoll).

As we slowly come to know more about the man called Ove, we watch as the newcomers in his community, most especially Parvaneh, make inroads into his inner life. He tries to rebuff her saffron scented tubs of chicken and rice ("Why try to make it Christmas every day?" "What's wrong with boiled beef and vegetables?" he asks himself), but there is no disputing that these foreign dishes warm him with nourishment beyond the somatic.

I have a soft spot for these sorts of little narratives of community. Fellow Scandinavian, the Norwegian writer/director Bent Hamer, created a community of two in "Kitchen Stories" (2003), based on the post-World War II Swedish research project involving placing an observer on a ladder-high stool to observe Swedish housewives in their kitchens. In Hamer's imagining, the research centers on unmarried men not women, and in the course of "Kitchen Stories," researcher and subject, in something of a human inevitability, become friends. In "O'Horten" (2007), Odd Horten is a 67-year-old train driver on the eve of retirement. The film charts his, at times clumsy, attempts to leave his old community on the route between Oslo and Bergen behind and surrender to the possibility of the new.

Though most often noted for his social criticism involving themes of class and labor, British director Ken Loach approaches his critiques in narratives set among community. Looking at the most recent decade in a career that has spanned a half century, "The Wind That Shakes the Barley" (2006), "Looking for Eric" (2009), "The Angels' Share" (20012) and "Jimmy’s Hall" (2014) recall, like Kirk Jones's 1998 "Waking Ned Devine," the golden era of Ealing Studios – the oldest continuously working studio facility for film production in the world – that churned out one memorable little movie after another, including the 1949 "Whiskey Galore!" directed by Compton MacKenzie, Charles Crichton's "The Titfield Thunderbolt" (1953) and Alexander Mackendrick's "The Ladykillers" (1955). What these films have in common is that the material object of the quest is merely a vehicle for the quest's larger purpose: the power to bring community together. In these narratives, community, not family, functions as the central social unit, the ultimate source of human meaning and communion.

As "A Man Called Ove" unfolds, the constellation of neighborhood characters – who have known, not only Ove over time, but his wife Sonja, a teacher and nurturer at heart – must remind Ove of Sonja's spirit of laughter, love and giving. Ironically, it is something this old crab does again and again in spite of the fury Sonja's death and his consequent loneliness have engendered in him.

Watching "A Man Called Ove," one is struck by the diversity that comfortably inhabits European cinema – the Iranian Parvaneh and her children, Mirsad (Poyan Karimi), the gay teen thrown out by his father to whom Ove gives shelter. The only American directors I know of who incorporate immigrant actors and characters as casually as French, Belgian and various Scandinavian directors do are Ramin Bahrani who was born to Iranian parents in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and Jim Jarmusch, whose casts and crews are enviably international. I believe this is a timely observation to make in a country that ostensibly asks to "Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed, to me."

This is what Ove's beloved Sonja has taught those she touched in life through actions, not words. They are the words Ove's flawed neighbors somehow inherently understand without having to say them. They are the words that herald America's safe harbor – a safe harbor we have closed to so many across a war-torn globe.

“A Man Called Ove”

In select theaters

Director: Hannes Holm

Writers: Fredrik Backman, Hannes Holm

Stars: Rolf Lassgård, Bahar Pars, Ida Engvoll, Filip Berg

Music: Gaute Storaas

Cinematography: Göran Hallberg

Rating: PG-13

Running Time: 1 h 56m