Letter About Charles Giuliano’s Seventh Book

Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 1870-2020: An Oral History

By: Bill Wadsworth - Nov 05, 2021

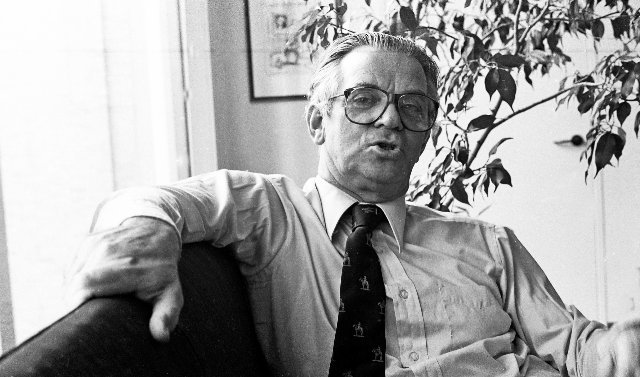

The poet and Columbia University professor, Bill Wadsworth is a neighbor and friend. He has been on the road for the past month. I sent an e mail inquiring when next we might enjoy another witty and insightful literary luncheon. His response comprised a critique of my current MFA book. This ‘review’ is posted with his permission.

Charles,

What a journey! I spent the month of October, a month spent almost entirely on the road between NY and VT, immersed in your oral history of the MFA. As I traversed the map back and forth, spending time with family and old friends, going back over my own long-familiar (and familial) ground saturated with more than fifty years of memories, I was also traversing a parallel universe, a vast terra incognita occupying the same stretch of history. Boston and its unique cultural matrix and layers of social strata, the history of the art world in Boston immersed in still-controversial and unresolved issues around art and appropriation, art and imperialism and colonialism and elitism and racism and sexism, art and its relationship to the public and local communities, art and money and power, the whole milieu of museums and galleries and collectors and curators: your book contains it all within the microcosm of one institution and a chorus of its leading actors. I was fascinated in part because I’ve had my own intimate acquaintance with many of these issues in running cultural institutions, and being tossed around – often very much in the public eye – by the forces that have roiled through our culture and body politic over the decades. It was also interesting, as a born and bred New Yorker, to see how different the perspective is from Boston when surveying those same decades.

As a poet by vocation, neither a journalist nor scholar, I’m in awe of the depth of your research and knowledge of the field, combined with your grasp of the issues at hand and willingness to go head-to-head with so many powers that be. The encyclopedic reach of your mind applied to art and artists, whether ancient, classical, modern, or contemporary, is dazzling. That you can know so much (and care so much) about the art universe, at the same time you have another self who has done the same in music and theatre, never mind more generally in regard to the history of the counterculture and politics in our time, is just staggering. Clearly all the drugs, sex, and R&R never slowed you down or fogged your windshield.

Your follow-through, as well, is astonishing. The core of the book is the series of interviews you did in 1975-77, when it appears that the museum’s struggle to find its way very belatedly into the modern world reached crisis pitch. From the moment of the 1970 ad hoc committee report, and the subsequent downfall of the formidable Perry Rathbone, the MFA appears to have been enveloped in one cloud after another of controversy and internal and external drama and discord, and it seems you were in the middle of it all like a correspondent in a war zone with bombs exploding left and right, recording everything. But even more impressive is the way you continued to follow the story through the 80s and 90s, and then went back all these years later to interview the surviving players, one more time again, to discover how it has all played out.

The story itself in its own way is worthy of Game of Thrones, but with a crucial difference. With very few exceptions, in spite of their obvious differences with each other, there seem to be no simple good guys or bad guys (except maybe some characters named Simpson and Kelly and Cairns, but they’re all kept offstage). Though you hit your subjects hard, one after another, with tough questions and challenges, every one of them comes across as sympathetic, and your even-handed respect for each one and his/her point of view is remarkable. Your own strong opinions and advocacies are made clear over and over – about the stultifying conservatism, snobbism, elitism, sexism, and racism of the Brahmin class and its dead hand on the museum they considered to be their private fiefdom; the failure of the museum to embrace modern or – at least until recently -- contemporary art outside of the narrowest range of abstract formalism; its failures to connect with the public in a meaningful way and embrace cultural diversity; its failure to support local artists, including Jewish artists, and condescending relationship to both the ICA and the National Center of Afro-American Artists; its inability, in spite of the wealth of its collection, to keep up with museums in Chicago, Philadelphia, Minneapolis, and L.A., much less NYC. It seems to have been an institution that peaked at the turn of the century with its Impressionist collection, and ever since has been trying, but repeatedly failing to some degree or another, to revive itself as more than a grand parochial monument – in some ways, like the city of Boston itself?

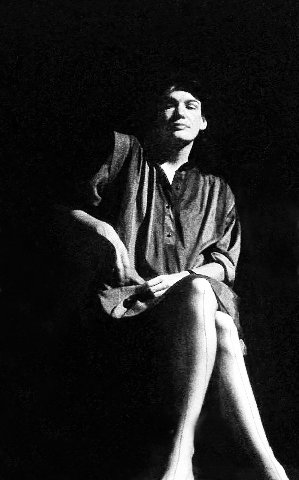

Your book is dense with facts, and dense in the web it spins around the myriad ways that all these issues intersect with the realities and practicalities of institutional stewardship and management, from boards and fundraising, to finances and organizational structure, to personnel and space management and bricks and mortar, to marketing and public relations, and of course to politics, public policy, and power. But what stands out as most compelling – and this is where the interviews are so invaluable – is that it’s a book about people, about certain compelling individuals whose lives and professional expertise and passions and achievements and failings have put the flesh on the bones, the air in the lungs, the blood in the veins, of the museum’s dramatic postwar history. The directors (from imperial Rathbone to troubled Rueppel to narrow but competent Fontein to poor Shestack to the successful and domineering “declasse” Rogers to Teitelbaum, left to pay off his predecessor’s debts in a time of plague and yahooism); the powers above them (from the corporate parvenu Seybolt to the Brahmin wheeler-dealer Cabot, to admirable Johnson and Gund to the dreadful Koch); and especially the brilliant curators (Moffett, Stebbins, Lighthill, and Locavara) comprise an epic cast full of darkness and light, genius and tragic flaws. I confess that I was most drawn in a way to the ones who didn’t survive their tenures, who seemed most to be the victims of fate: directors Rueppel and Shestack and curator Lighthill (who of them all seems to be the one closest to your heart in her forward-thinking views and advocacy for Boston artists).

Again, this is an extraordinary and invaluable history. I loved the way it started, with your preface recounting your two years of initiation in the basement, assembling shards from ancient Egypt. The book’s structure is most problematic from there to when the interviews ca. 1976 begin to flow. There are a lot of redundancies and repetitions of facts and anecdotes from one section to the other, sometimes even repetitions of the same sentences or phrases word for word within a couple of pages of each other, so that the first third or so of the book keeps doubling back on itself. Once the chorus takes over, the book for the most part sails forward. That said, it’s clotted throughout with too much incidental information – way too many dates in parentheses, lists of exhibitions and board members, too many budget details – that would have been better relegated to footnotes or appendices. So much ancillary info embedded in the main text makes it distracting and slow-going and at times confusing. It’s hard to keep the narrative thread clear in the reader’s mind. I wish there were an index and things like a chronology showing the museum’s timeline and directors’ dates of tenure, etc. on just a page or two. Which is only to say that I wish you had had a professional editor and editorial team (including a copy editor and proofreader) at your back to support such a vast and compendious undertaking. Your mind is vast and compendious – but properly organizing an entire book as all-encompassing as this takes a village.

One of the things I appreciate most about the book is the way it tells the story of an institution through the lens, and in the voices, of those who worked within it, and to some extent gave their lives to it. Famous artists are kept in the background (though the great works of art are not), and the spotlight is on the administrators and the curators. For someone who made his career as an arts administrator, and who recognizes so much that comes with keeping a venerable institution vital and relevant (and solvent), from the bloody struggles over budgets, internal power politics, economic and social roller-coasters, personnel management, to momentous decisions about mission and aesthetic priorities, this book accomplishes something rare. It stands in the end as an homage to everyone who did their best to move the best in culture forward. They, including the ghosts, should all be eternally grateful to you.

I look forward to that bottle of wine.

Bill

The author will discuss the book at the Williams Faculty Club, at 7 PM, on Friday, November 19 at 7 PM. Protocol entails wearing masks and producing proof of Covid-19 vaccination. The club is located at 968 Main Street Williamstown, MA 01267. It is parallel to the 62 Center theatre. The event is free and open to the public.