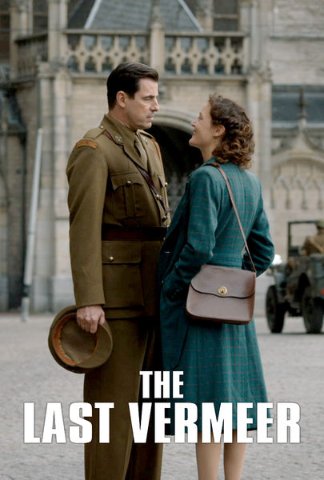

The Last Vermeer

Art of Forgery

By: Jack Lyons - Nov 21, 2020

In the sometime labyrinthine and complicated world of art and paintings for sale of the great masters over the centuries, it is easy to get lost in the authenticity, and/or forgery issues, plus ownership claims that occur when money blends with desire on the part of collectors, museums, and the prestige that comes to the owners of such art treasures.

Following World War II, the Allies created commissions to insure the return to the rightful owners of the art masterpieces that had been stolen and hidden by the Nazis during the war years.

“The Last Vermeer”, a TriStar Pictures film based on the book “The Man Who Made Vermeers” by Jonathan Lopez, opened in over 800 ‘live’ theatres on November 20, 2020; centers around one such court case and trial reparation event in the Netherlands in 1945.

The War in Europe ended with VE Day, May 8, 1945. Over 23, 000,000 European civilians perished. Collaborators were being executed in public squares in cities all over Europe. The survivors from Nazi-occupied countries began seeking revenge on the collaborators and war profiteers. Passions were out of control as public executions by government officials were taking place in public squares throughout Europe.

Long-time American hands-on producer Dan Friedkin, now a first-time film director, brings to the screen the probing and dramatic story of the notorious 20th-century Dutch art dealer, painter, hedonist, aesthete Han van Meergeren, who sold Dutch art treasures to Hermann Goring and other high ranking Nazis during the war years making millions in his dealings with the Nazis.

Reverence for the Netherlands Golden Age of Dutch masters practically borders on being a religion in Holland. Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, and Pieter de Hooch are but three giant names that quickly come to mind. The Dutch style of painting in the ‘Golden Age’, inspired new lighting techniques for 17th-century Dutch painters who credit Rembrandt and his style, of creating and capturing in his brush strokes the skill and magic that influenced painters that followed for generations to come.

The story in short is set in Amsterdam in 1945. Canadian Captain Joseph Piller, a Dutch Jew, who fought in the Resistance during the War, is stoically underplayed by Danish actor Claes Bang. The witty Bon vivant art dealer Han van Meergren is sensationally portrayed by Australian actor Guy Pearce, in a highly nuanced bravura performance that should nab him acting nominations from several festivals from countries where the film will be screened (despite the pandemic).

After WW II ended in 1945, Piller becomes an investigator for the Allied Commissions assigned to the task of identifying and redistributing stolen art, resulting in Dutch art dealer Van Meergaren being accused of collaboration – a crime that brings a death penalty if convicted.

But, despite mounting evidence, Piller, with the aid of his assistant Minna Holberg, played by well known, wonderful, European actor Vicky Krieps, (who is wasted in a small role in this film), becomes increasingly convinced of Van Meergren’s innocence, finding himself in the unlikely position of fighting to save his life (Shades of Tom Cruise as Jack Reacher in the eponymous 2012 action movie). Solid supporting turns come from Roland Moller as Piller’s security enforcer and aide Esper Vesser and Adrian Scarborough as Dirk Hannema, the art critic expert as a witness for the prosecution in Van Meergaren’s trial for collaborating with the Germans.

Movies about art heists (“The Thomas Crown Affair” with Steve McQueen and its later re-do with Pierce Brosnan had a certain sophistication and style to their storylines. “The Last Vermeer”, however, is a richly textured film set in post-war ravaged Europe. There no glamour there just the appropriate grit and destruction that the legacy and folly of war provides. Non-the-less the technical credits along with the performances are first-rate.

The production design by Arthur Max brilliantly recreates Amsterdam of 1945 both externally and internally. The courtroom and trial sequences have the ring of authenticity as do the period costumes of Guy Speranza. I always find the courtroom dramas fascinating in the rules and the cultural differences in Europe from our American and English court systems.

Director Dan Friedkin and his cinematographer Remi Adefarasin, have spiced up the film with creative camera angles and movement. Unfortunately, for me, the script by James McGee, Mark Fergus, and Hawk Ostby is the weakest link in this production that had promise of being a serious candidate for box office success by the nature and the appeal of its premise and its subject matter.

However, the final arbiter of success in the film business is always the audience. Small stories produced by independent filmmakers have a way of becoming big box office when the planets are appropriately aligned. In 1955 relatively unknown supporting actor Ernest Borgnine and the intimate film “Marty”, walked away with Oscars for Best Actor and Best picture. As Oscar-winning screenwriter William Goldman once famously said about Hollywood “nobody knows anything.” The proof of the pudding is in the eating of it. So check out “The Last Vermeer” for yourself.

Posted courtesy of Desert Local News.