Lucy Dhegrae at National Sawdust

Giving Voice to Rape

By: Susan Hall - Nov 24, 2019

Lucy Dhegrae is National Sawdust Artist-in-Residence. She has conceived The Processing Series. Part I, More Beautiful than Words Can Tell, was produced this weekend. It is an extraordinary work, a response to a long ago sexual assault on the artist. Keeping the experience to herself, Dhegrae continued to be able to speak. Speech is of course very much within our own control In singing, we place ourselves in the hands of others, composers who have created a work. Dhegrae was unable to sing. She was unable to trust herself to another’s hands and music.

Part I is a musical portrait of the paralysis and its subsequent working out. Dhegrae came to see that in order to heal, she must learn to sing again. Her moving journey to mastery of her vocal cords, breath and projection was like reclaiming her vagina. Large screen images of the folds of the vocal cords are very much like those of a woman’s personal parts. The journey is ripe with powerful emotional content, the stuff of song.

We have become accustomed to contemporary composers’ exploration of the organization of sound into music. Drums began this journey, and Dhegrae’s passage to song is marked by a wild use of beating the body by Vinko Globokar. Sticks and rocks were the earliest forms of music.

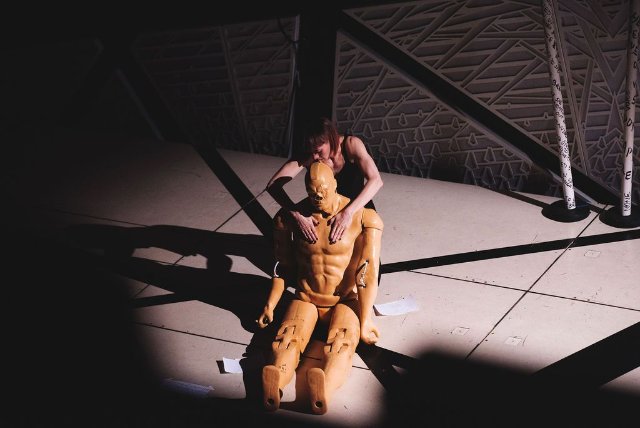

Globokar's Corporel, which means 'of the body', was performed with a large demo man puppet, there to teach how to defend against assault. It is a very physical piece. The composer points out that singers use bodies to create their work. Yet performance is supposed to be a non-physical experience. What has happened here, rape, is above all physical and the self defense lesson that accompanies Corporel never lets you for get that.

Globokar is interested in the use of the body to produce sound. He notes that singers are rarely able to use the body beyond its breath and manipulation of the vocal cords. He finds this odd. Singers do too. Defense exercises are pounded on the body of a dummy male. The sounds of beating are crucial. They remind us of the drum’s skin. Globokar provides an opportunity for Dhegrae to undertake her self defense as she explores the body.

Utterances are offered by Jason Eckhardt, whose Dithyramb, a hymn from Tongues, opened the evening. Dhegrae explores sounds, not spoken, but uttered during moments of intense feeling. The variety of sounds called forth suggest both a chaotic personal state, and wild appreciation of cackles, hee haws, vowels and consonants we have at our beck and call.

Bethany Younge’s Her Disappearance filtered sound through PVC pipes and felt desperate and often shrill and breathful. You felt the struggle and in the end no resolution. Whispers, beats, runs and scratches followed the disappearance.

Maria Stankova’s Rapana is a lullaby to celebrate a birth. It is known that by 4000 BCE the Egyptians had created harps and flutes. Performed with a flutist often walking side by her side, Dhegrae sing's her first beautiful recovery notes. A rebirth is celebrated.

The world premiere of Osnat Netzer’s Philomelos brought us to the daughter of Titus Andronicus, Lavinia, who was raped and then had her tongue removed so that she could to speak her assailant’s name and her hands cut off so she could not write it. Sand is on hand, for this is the material that Lavinia, and Philomelos before her, would use to identify the assaulting man. Mixing sounds of nature and music, the powerful presence of a woman who can identify her assailant by whatever means available, seeps into the listener's consciousness.

And finally with almost Glass-like repetition, Dhegrae learns to say no in Caleb Burhans song by that name. The word becomes beautiful, and, as we know, the way to keep ourselves safe. We were all invited to dance and celebrate at the performance's conclusion.