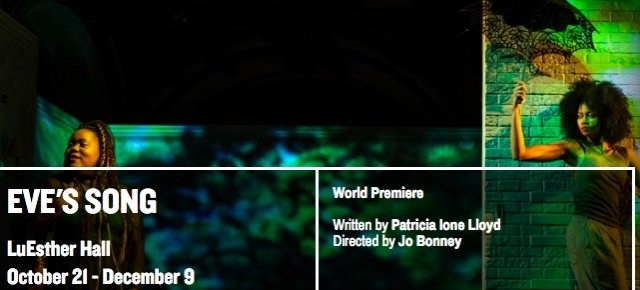

Eve's Song at Public Theater

Patricia Ione Lloyd Is Playwright in Residence

By: Rachel de Aragon - Nov 26, 2018

Eve's Song is being presented at the Public Theater in New York. "The Funeral Procession" by Ellis Wilson hangs prominently above the dining table against the white flocked walls to place us in the epitome of an African-American middle-class home. Ecru cloth napkins, straight-back, dark-wood chairs and glass scones on the walls, we wonder whether anything could possibly ever be out of place. Riccardo Fernandez creates a setting which is both understated and symbolic as the backdrop for dramatic use with lighting by Lap Chi Chu and sound design by Elisheba Ittoop.

But the invulnerability of middle-class achievement is haunted. Pervaded by the present staccato-like news flashes from the television tell of black men shot, killed, dead . “We” don't discuss that sort of thing at dinner. Dark phantoms, shadows of women slide along the corridor where fear is a weakness which is not part of who 'we' are. Director Jo Bonney captures this brilliantly.

The family itself is no longer 'whole'. A divorce after 22 years of marriage has left Deborah (De'Adre Aziza), skillfully understudied by Patricia Lloyd for this performance, to hold the family together. Deborah believes that politeness, good grooming and nutritious meals can protect the family. Her vulnerability is palpable as she keeps the world at bay by turning off the news. Her adolescent children, Mark (Karl Green) and Lauren (Kadijah Raquel), are struggling with the realities of their own emerging adulthoods and well as their parents' divorce. Although it would seem that neither Lauren's coming out as a gay young woman, nor the racist harassment that Mark encounters at school, break through the impenetrable wall of platitudes that forms their family dinners where the walls have literally begun to crack.

Lloyd braids the painfully routine with humor, horror, and romantic hopes and abandonment. Raquel is able to bridge these moods with grace. She gives us both the joys of sexual discoveries and the anguish of her anger. Her new love, Upendo (Ashley D. Kelly) brings a feisty voice of protest and social criticism which begins to intrude, confront and alter what is said at 'our' dining table. What has been torn open is the fragility of the pretense and the vulnerability of those who believe their lives can exist separated from the world around them.

When Upendo first meets Lauren, she is trying to remember her song, “the song all the molecules in your body hum before you have an orgasm …the song on the wind in the garden of Eden.” She tells Lauren, “We remember our song when we die and we sing it with the spirits that come to take us in death.”

The metaphor is picked up throughout the play, as the Spirits move to the rhythm of the stories which have taken their lives. As they speak, you feel that you remember reading of these tragedies somewhere in a small paragraph in the newspaper. These are the stories of their deaths. They are the spirits of murdered women. Their dance-narrative carries the solemnity of the funeral procession ( Stephanie Batten Bland) heightened by gunshots and Hana S. Kim’s flashing, chalk line-like projections.

Spirit Woman, Kerrice Lewis (Rachel Watson-Jih) a beautiful young gay woman who has been shot 15 times and set on fire in the trunk of a car tells of last moments hearing her cell phone ringing. Spirit woman, Amya Tyrae Berryman (TamaraWilliams) reminds us of intrinsic vulnerability in an biased and violent society. She was shot; “as soon as they knew I was trans”. Spirit woman, Katheryn Johnston (Vernice Miller), with the strength and fragility of an ancient carving, commands our attention as she tells us that she is so old everyone she ever loved is dead. At nearly 100, she was shot by police who mistook her home for that of a drug-dealer.

Can there be a place of safety where nothing bad can happen, as Deborah has assured her children? Does the violence of social biases always threaten our comfort zone? Does compliance assure protection? Deborah is herself a victim of racial stereotyping, sexual harassment and biased assumptions despite her six figure compensation. We are invited to laugh, fear and think. As in life itself, there are no easy answers.