Wes Anderson's Moonlight Kingdom

Film Wins Five Independent Spirit Awards

By: Susan Hall - Dec 01, 2012

Wes Anderson is a superb filmmaker in the tradition of the great film directors. One of his haunts is the Thorne miniatures room at the Art Institute of Chicago. These miniatures also launched Orson Wells’ career. When Wells received his Academy Award for Citizen Kane, he was asked to what he attributed his success. He replied, “Thorne,” but everyone thought he was talking about the Rosebud.

No, Wells, when he first saw the Thorne rooms at a World’s Fair, before they were ensconced at the Art Institute, realized that natural light was far more dramatic than the kliegs shining down from the ceilingless sets of yore.

For Anderson, the Thorne rooms are models for miniatures, and another way of creating objects on his sets for films prompted by emotional longing. In a fascinating assemblage of a tall lighthouse and the Island Police station rising up from what appears to be a point of Point Judith, RI, you see immediately Anderson’s purpose: the constancy of color and shape no matter the time of day, or the weather; the isolation of the scene from the world of which it is a part, the odd proportion to live human figures and the surrounding countryside all at first jar and then become familiar.

In the interior of the lead actress’ home, the rooms are not miniatures, but the lighting and the placement of the furniture and staircase have the same effect as the tiny Thorne settings.

The overall impact of Moonrise Kingdom, Anderson’s latest and most successful work, is operatic. In a post screening Q and A, beamed by satellite from New York to the German border near Poland where Anderson is preparing to shoot The Grand Budapest Hotel, scheduled for a 2014 release, Anderson said that he had begun to construct his film with Benjamin Britten’s Noye's Fludde, an oratorio composed by Britten in the style of the 13th century oratorio.

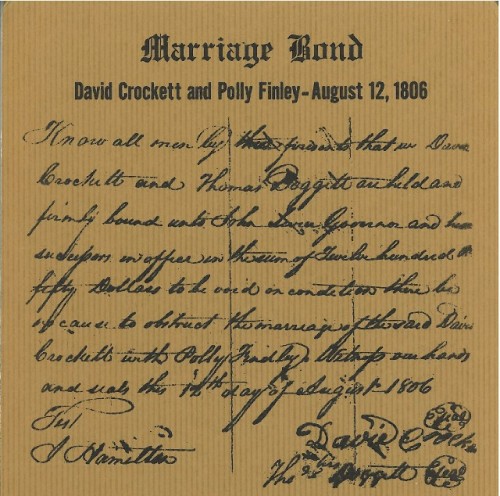

Growing up in Houston, Anderson had performed the piece in church. In his film, the twelve-year-old boy Anderson wishes he had been and a girl who appeared in the oratorio with him, agree to run away together as a Katrina/Sandy type storm approaches. Anderson easily has you believe that they will make it on to the ark, two by two, Sam the boy looking to all the world like Davy Crockett as he dons his coonskin cap.

The real Davy ran off with a bride to be at twelve, but we are in an Anderson fantasy, not Davy’s. We root for their marriage, even though the scout who officiates says he is not sure the ceremony is legal, but if they are really committed to each other, it counts.

The Anderson’s usual suspects are rounded up to act. Bill Murray does a wonderful turn with Frances McDormand, Edward Norton and Bruce Willis, singled out now for an acting award. Bob Balaban, billed as narrator, creates a straight-faced Al Roker weatherman. If the ark is going to sail, the weather report is all-important. Roker, I suspect, has never before been dressed as an elf in green and red. Launching a big yellow balloon to measure the weather, Balaban also seems to launch the moon.

The special touches go on and on. The 1965 telephone operator looks like Lily Tomlin’s Ernestine. In a wonderful, sad scene between Police Officer Willis and Sam’s foster father, Mr. Billingsley, the two rooms, literally separated by miles, are jammed together, but the dividing wall is only as high as the police station phone bank. It made me feel more intensely the dialogue, which concerned Sam’s rejection by his foster Dad and the police officer’s touching disbelief that any one could do this to a child.

Battening down the hatches is the act required at every turn. Through composed with Britten, Midsummer Night’s Dream and a Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra as well as Noye's Fludde as a torrential storm threatens the New England coast in 1965, all the diverse elements are seamlessly woven together.

Hank Williams underscores the Davy Crockett-Sam escape (Davy had fallen in love at twelve and gone exploring with the object of his affection). Anderson evokes the yearning for the wild we still experience. His labyrinth of woods and rocks blurs boundaries between the escape, the passion and the form. In this world none of the adults can achieve the intimacy and attachment the kids can.

Using film cameras which are held close to the body at about the height of a twelve year old, Anderson effortlessly captures their perspective, to which he adds look downs and look ups that help illustrate the complex problems pre-teens have.

Anderson said he prefers film to digital images. Film is of course three-dimensional, a digital image, two. Many of Anderson’s newly created objects are appropriated from the avant garde, but the emotions are more universal than vampires and Bluebeards. The Quay twins feel weird by comparison. Anderson’s story can be understood by anyone, and its universal feelings bind the audience.

Earlier this week, Moonlight Kingdom received back-to-back honors with five independent Spirit Awards after winning the best feature film award from Gotham. Academy members are taking note. Anderson’s films, rooted in meaning, accident, marginalia and idiosyncratic, handcrafted details, are rich in reference and also in dark humor. They defy description. One is left with a lingering satisfaction, surely the mark of great filmmaking.