The Prisoner by Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne

Large Questions at Theatre for a New Audience

By: Susan Hall - Dec 09, 2018

The Prisoner

By Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne

Lighting by Philippe Vialatte

Set Elements by David Violi

Costume Elements Alice François

Theatre for a New Audience

Polonsky Shakespeare Center

Brooklyn, New York

Through December 16, 2018

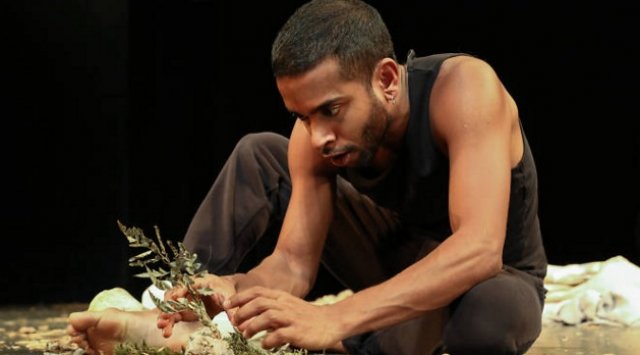

The set is spare and quiet. David Violi has scattered some sticks across the stage. A recessed room dips back from the hill in a front of a prison, which is imagined where the audience sits. Doors on either side of the stage are used by actors for entrances and exits.

Lighting by Philippe Vialatte singles out characters and also divides scenes, as the stage goes to black. Casual clothing is interrupted only once, when the woman in the prisoner’s life and the mother of his child appears in a suit after she has graduated from school and begun work.

We are in a neutral country, anywhere in the world where crimes are committed and people are punished. The question that pervades the quiet space of this moving drama concerns appropriate retribution.

Afghanistan may be the location. It was here that the creator and director, Peter Brook, heard the story which propels this drama. A narrator on stage introduces it. A man has committed an unspeakable crime. At first we are not told what it is, but will see the murder of his father. His brother takes a stick, which looks like the sole Becketian leafless tree on the set, and drills its spiked end into the criminal legs.

The community decides not to imprison the murderer but have him sit on a hill and contemplate a prison.

Over time he is visited by his woman and brother. He befriends a rat who tickles him like crazy. He kills the rat, roasts it over a fire and eats it. He is visited by a tree cutter with an axe. The prison would like to reduce its population of prisoners and hires the cutter to chop off prisoners' heads.

More time passes. The Prisoner looks like a desert visionary, his eyes gleaming with other worldly light. His woman visits with his brother.

The only clear sounds we hear in the drama, besides the rat squeaking, are the collapse of the prison when it is bulldozed.

The narrator returns, and cannot find The Prisoner, or any trace of him. Nor can she find the prison.

In this quiet, beautifully directed and acted story, the questions of crime and punishment are inexorably and movingly raised. We are held captive by the Prisoner, Hiran Abeysekera as he struggles to understand why he is on the hill in front of the prison. The object of his gaze becomes irrelevant over time, and so there is no prison and he is no longer a prisoner. We come to the quiet conclusion that the issue of punishment can be resolved without incarceration. It seems so obvious here. Why is it not so in the world today? A haunting question posed by Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne disturbs and mesmerizes.