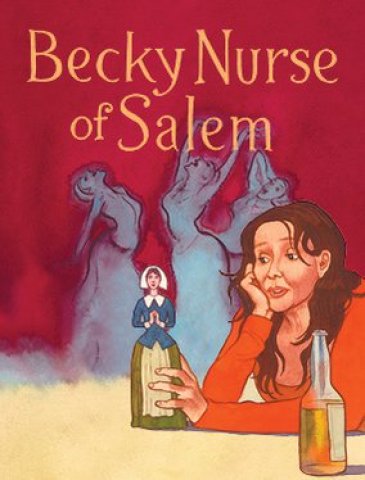

Becky Nurse of Salem at Lincoln Center

Sarah Ruhl Tackles Witchery

By: Susan Hall - Dec 20, 2022

At a family reunion in Prides Crossing, Massachusetts, James Howe, the organizer, announced that the state of Massachusetts had pardoned our relative, Elizabeth How(e) who was hanged in Salem on July 19, 1692, with Rebecca Nurse, whose ‘witchery’ is the subject of the play, Becky Nurse of Salem.

About a hundred 20th century relatives of Elizabeth's were at the reunion. In a thick volume, a copy of which is housed at the New York Public Library, about 8,000 family members are listed at the beginning of the 20th century. Among the ones I know, there was a collective and amused sigh of relief when Elizabeth was exonerated. No, we were not descended from a witch.

Rebecca Nurse, Elizabeth’s sister-in-law, has been pardoned too. Times change. The role of women has also changed.

Playwright Sarah Ruhl has treated historic subjects by embedding them in new material, like her libretto for the opera Euridyce. Now she takes Rebecca Nurse through three centuries.

Ruhl is lucky to have the incomparable Dierdre O’Connell in the lead role. Yet a dashing performance by the Tony Award winning actress is compromised by the play. We are mixing in not only court records from the 17th century but also Arthur Miller’s classic take on the trials, The Crucible.

In a Boston secondary school, distinguished actress Mildred Dunnock’s daughter once played Abigail. At 17, she was closer to the real character’s age (11) and hotter than Madeleine Sherwood, who created the role and sent a telegram, posted for all to read. Ruhl attributes Miller’s interest in the subject to his intense desire as a married man to ‘fuck’ the young Marilyn Monroe. This seems a stretch, but is confirmed by Miller’s daughter.

What to make of the play? Recently Mark Adamo, who had been obsessed for decades with Euripides' Bacchae, took that work as a jumping off point for the libretto of Lord of the Cries, composed by John Corigliano. The integration was seamless, with Anthony Roth Costanzo, a powerful acting singer, bringing together past and present. Adamo thought that Euripides infused most of the opera. This did not seem a concern of the audience, who loved the work. What mattered was the successful integration of a past work with a present one, set in the 19th century.

The temptation to look back is easy to understand. If you have monumental and successful works of art to draw on, you don’t have to begin at the start line. You might feel you are halfway home. Yet the challenge of bringing the past forward is great. And Ruhl gets it mixed up not mixed in. She is not helped by the direction, which can not decide on a style to help differentiate time periods and changing perceptions of the lead character.

Historians debate what prompted the Salem witchcraft trials. Did the town and the surrounding village quarrel about sharing responsibility for providing wood to a new minister? Was the hot-headed minister Cotton Mather the instigator? We still don’t know the prompts. Yet these women, among them Elizabeth Howe who I’ve come to know as best as I can, were not as badly off as contemporary women who rally to their cause would have you believe. Or perhaps it’s best to say they were not less fortunate than the men who also survived bitterly cold winters and food shortages.

Ruhl makes the case for love triumphant. Elizabeth Howe was a woman who thrived on the loving care of her blind husband. That was over three centuries before the current playwright discovered love as the solution for her character’s happy ending.

Historical note: On Sunday May 29, 1692, Elizabeth was at her brother in law John's home in Ipswich, when a Constable Ephraim Wildes of Topsfield arrived with her arrest warrant. Goody Howe pleaded with John to accompany her to Salem, even offering him ten pounds if he would. Apparently scared by the accusations swirling around the Massachusetts countryside, but also because his wife's sister, Rebecca Nurse, had already been accused of witchery, he refused to go. More pleading by Elizabeth made him reconsider. "If you will tell me what you did as a witch and who you harmed,” John insisted, “I'll go with you." Elizabeth vowed that she'd never been a witch and left alone with Constable Wildes.

At her preliminary hearing, Elizabeth was accused by her neighbors, the Perleys, of reducing their cows’ milk to a dribble. Almost as an afterthought, the Perleys claimed Elizabeth caused their daughter’s death.

Elizabeth, charged as guilty, was placed in jail to await trial.

The next day John was standing at his door talking to a neighbor when his sow suddenly leapt three feet into the air and fell down dead. John cut the sow's ear off to see if she'd been bewitched. When he did, the hand in which he held the knife became numb and then painful. John was unable to work for several days, a sure sign that the sow had been cursed, probably by his sister in law.

At Oyer and Terminer a month later, several young girls feinted when Elizabeth took the stand and she was ordered to come down onto the courtroom floor and revive them. This proved her powers and her possession.

Although many local residents testified to Howe's good character, their opinions did not count. Elizabeth's indictment was signed on July 1st. On July 19th she was hanged and buried at the spot where she dropped.

Becky Nurse of Salem at the Mitzi Newhouse Theater Lincoln Center. Tickets here.