Boyhood: Film of the Year

Talking with Director Richard Linklater

By: Susan Hall - Dec 27, 2014

Marcel Proust would have loved Boyhood. Those thick layers of time he was able to put on the page in his search have now been placed on the screen by the brilliant film director and auteur Richard Linklater. When I mentioned this to Linklater, a smile spread across his face. Of course. Proust.

There is not a wasted moment in Linklatter's accumulation. Time may fly, but it seeps in layer by layer, minute by minute. Boyhood hits you in deep, hidden places.

I asked Linklater at a recent screening if we were watching and listening to his script on screen. He said every moment was scripted.

So how did he achieve the feeling of being in the real moment of the actors? Rehearsal, probably like Ingmar Bergman who also took his troupe to an island.

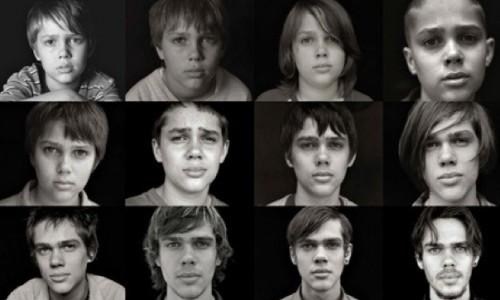

Year after year for twelve years Lorelei Linklater, Patricia Arquette, Ethan Hawke and the film’s star, Ellar Coltrane, met for about three weeks to rehearse and then shoot for five. The actors came to accept each other in roles. Arquette said that ‘her children’ would ask for food when they were hungry. She morphed from in loco parentis to parent. When Coltrane had trouble with his ‘real’ parents, Arquette helped him sort things out.

Linklater suggested that his mother may have inflicted multiple, disastrous father substitutes on him. But it is so clear that the mother is trying here. She protects her cubs even as she puts them in harm’s way with an alcoholic husband and generally poor taste in men.

So many children are brought up by single parents today. How many of us look back and wonder if we could have made it with the children’s father? Certainly the father played by Ethan Hawke is flawed, but he is also a wonderful Dad. The kids thrive in his gaze, in his car, even with his born again new family.

Sandra Adair edited the film. From their first discussions Linklater wanted no artificial delineations between Years I and 2. Time’s passage would be reflected in cuts not in wipes, dissolves, and notices.

The effect of this approach is a life as one eternal moment. Time changes, but the moment does not. The life of one small family. A single mother tries to hold the unit together imperfectly. She never slams the door on the father of her children. She accepts him as he is: charming and fun and erratic, until he finally settles down and celebrate his son’s rite of passage to the end of boyhood in redneck style: gifts of a Bible and a gun.

The film is like a wallop. One big wallop to the gut. But there is this odd relief in knowing that we are all grace notes on the earth’s crust. Two scenes in Texas parks place us in Proustian time. It is the thickness of the world’s time we have in many very dense scenes and complex personalities that grace the screen. The scenes are breath-taking and yet anchored by time-framed people in a timeless place.

The scenes are complex and rich in texture. Yet because they ring true in Linklater’s hands, they never burden the viewer. The film is entirely from Mason Jr.’s point of view, but this is not achieved by phony camera angles, but rather deep insights. Mason Sr. is an absent father, but the love he generates in his children is borne of a blind indulgence by both father and child. We forgive as we share.

There is no nostalgia here. Everything is fleeting. What accumulates are the images of several lives, brushing past us. We do not have to penetrate the surface to feel the pain and the joy. Like clouds they pass and cast lingering shadows.

The only film I have seen that comes close to this is Russian Ark, the one take journey through the Hermitage. Like Linklater Alexander Sokurov filmed the collection in one day. He was constrained by permissions. He rehearsed the all-important camera move again and again with the cinematographer, and the actors. Linklater does this too. Somehow this precision yields brilliantly sustained ideas in both films.

In Boyhood, we do not hold our breath as we do in the one perfect take. We are sucked in by Linklater’s mastery of time and somehow forget how very difficult making this film was. Linklater is one of the fearless and not so foolish people who trusts his idea and brings it off.

Occasionally the shadows cast by our thoughts are realized as a drunken man endangers his wife and children, for instance. We do not know that locations were chosen in part because they were accessible. Clemens is on the mound at Astor Park, and I thought of this father, known for strikeouts, whose children’s names all began with the iconic K. (Koby, Kory, Kacy and Kody.) Mason Sr. undoubtedly knew this when he took his children to see the great pitcher.

The project was funded by IFC. Some wondered how the producers kept their jobs over the years when nothing seemed to happen. But the rewards now are rich. The film is suffused with humor in a more gentle, subtle vein. It is a brilliant grace note.