Letter #3 from Southern California

Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980

By: Patricia Hills - Apr 19, 2012

In Letter 1 I offered my impressions of the Pacific Standard Time exhibitions mounted at the Otis College of Art and Design, the Getty Museum, and the Hammer Museum; and then, for Letter 2, I talked about the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach. The next two nights my son Brad and I camped out on couches at the condo that my daughter Christina and Shamus (her husband) were renting in Coronado, a suburb of San Diego on the ocean and adjacent to a naval base. Their eleven-year-old daughter (my granddaughter), Maggie, was performing in a children’s play that weekend in the fabulous Balboa Park. Another typical winter California day—a bright sun radiating warmth in contrast to the cool moments in the shadows of buildings and palm trees.

But back to the Pacific Standard Time exhibitions—Phenomenal: California Light, Space, Surface—split between two locations, in downtown San Diego and in La Jolla, which we saw on Saturday, January 7. Robin Clark, the curator for the SDMCA exhibition, explained the premises of the exhibition in the catalogue: “During the 1960s and 1970s, light became the primary medium for a loosely affiliated group of artists working in Greater Los Angeles who were more intrigued by questions of perception than by the notion of crafting discrete objects. Whether by directing the flow of natural light, embedding artificial light within objects or architecture, or playing with light through the use of reflective, translucent, or transparent materials, these artists each created situations capable of stimulating heightened sensory awareness in the receptive viewer.” Clark’s remarks succinctly express what we were about to experience.

The SDMCA light and space shows were Brad’s favorites. I had, of course, seen works by Robert Irwin, Larry Bell, and James Turrell in New York, but never, as I recall, in the Boston area. Checking the catalogue’s bibliography of exhibitions devoted to California light and space artists, I was astonished at the degree to which the East Coast had ignored solo exhibitions of these artists. The Whitney Museum had a Robert Irwin show in 1977 and a James Turrell show in 1980, and one could always see a few Larry Bell sculptures, but the East Coast seems mostly to have shown only its own light artist, Dan Flavin.

Why was that the case? Because of snobbism toward the West Coast? Because the patrons who support New York museums always preferred the kinds of objects that they could buy for their penthouse apartments? Or was it that Clement Greenberg and his acolytes, such as Michael Fried, found such work too theatrical, too performative? And what are the works anyway? Not objects, but installations planned with engineering drawings and new technologies, and using light to flood a corner or a corridor. Such works are theatrical, with us the players moving through elusive spaces and forcing our eyes to comprehend the blurred and unseeable.

To discuss all those works in San Diego with the wow-factor would be to write too much, so I will stick with the highlights. The downtown SDMCA (two buildings, actually) held Robert Irwin’s cast column, a clear acrylic prism twelve feet high, standing alone in a corner space surrounded by floor-to-ceiling windows. The guard told us that on one sunny day a woman came in, sat quietly on the floor for hours, and watched the rainbow moving slowly across the wall that had been cast by the sun reflecting through the gigantic prism. She probably considered it a pure Zen sensation. But with an overcast day, we had to forego that experience.

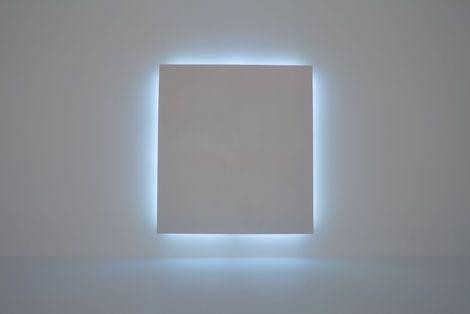

Upstairs, we encountered Robert Irwin’s Square the Room, 2007, which simply looked like a square space defined by flat walls on which were mounted works by Irwin. So where was the work called Square the Room? Then we realized that subtle lighting masked a scrim separating the square space from a much larger space behind the scrim. Why did our eyes not see this?

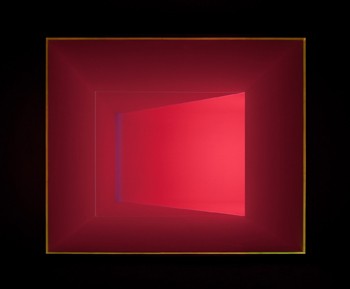

Another exhibition space contained James Turrell’s Wedgework V of 1975 that consisted of red fluorescent lights creating a virtual structure within the large dark space—a space that seemed to open to another large space. Gingerly approaching the demarcations between the two light filled spaces (Would I fall in? Would my steps be blocked?), I experienced that sense of sublime awe in which all rational thought disappears. I seemed to be in an elusive space of light and darkness wherein existence was nothing but pure intuitive sensation. Similarly sublime was another large space that contained Doug Wheeler’s light environment, Stuck Red and Stuck Blue, 1970. Here a wall bathed in magenta light within which hovered a rectangle of blue light was paired with a wall of deep purple light with a similar rectangle of cherry red light.

I have not even mentioned the Larry Bell glass panels (both installation and object), or the Mary Corse paintings containing glass microspheres, or the Craig Kauffman wall reliefs, described as synthetic polymer vacuum-formed Plexiglas with acrylic lacquer. The Corse and Kauffman were discrete objects of calm beauty, like those Chinese celadon bowls one sees in cases at the top of the grand staircase at the Metropolitan Museum.

Brad and I, joined by Christina, next drove some 14 miles to SDMCA’s La Jolla building, the back side of which hovers on a cliff above the ocean. Here our bodily experiences of the sublime intensified. We saw more of the same artists, including Irwin, Bell, and Wheeler, but also Helen Pashgian, John McCracken, Peter Alexander, and De Wain Valentine—all working with cast polyester resins, and other beautiful translucent synthetic materials developed after World War II. We had already seen similar works at the Getty Museum the first day of my California visit so the names were becoming familiar.

Three works stood out for us: Robert Irwin’s 1° 2° 3° 4° of 1997 is an altered environment consisting of three apertures cut into the tinted windows on the west side of the building that overlooks the ocean. The title refers to the four dimensions: height, width, depth, and time. Exterior and interior space thus had a dialogue with each other; the view of the ocean within the building with its tinted windows contrasted with the unobstructed vista obtained by the rectangular cutouts in those tinted windows. Art in California has to compete with the actual ocean landscape; in this work by Irwin, the artist frames and intensifies that reality.

Another installation we liked was Bruce Nauman’s Green Light Corridor, initially constructed in 1970, and consisting of a forty-foot-long structure of two ten-foot-high walls facing each other across 12 inches. Green fluorescent light flooded the inside corridor created by the walls. The museum guards benignly looked on as we shimmied sideways through the corridor several times, filling our retinas with such an abundance of green light that when our eyes turned away we saw pink everywhere. Photographs of Nauman’s structure are incapable of capturing that personal sensation of optical color saturation and relief.

But the chef-d’oeuvre of the exhibition was John Orr’s Zero Mass, an environment recreated from the original 1972-73 installation. Before I begin to describe our encounter with Zero Mass, to help you readers I turn to Dawna Schuld’s comment in her catalogue essay, which I read long after I experienced the work: “Light and Space art does not deal with light and space as media as much as it deals with the participating subject’s personal perceptual adjustment, a capacity that can be ‘flexed’ by extending one’s own experience in the extremes of sensory deprivation experiments, which take place on a continuum of perceptual experience extending into nearly total darkness and silence” (p. 118). That sentence makes sense when you do experience Orr’s work—as we did. We know the drill: when confronted in a museum exhibition by an opening in a wall, one enters and gropes along one of the walls, turning corners until one arrives in a dark space where one can then see something, often a video projection. That was not the case with Orr’s piece. Here, as I trailed my left hand along one wall, covered with paper, I sensed I had moved into the interior of a space that seemed, through my movements, to be large and oval. The darkness intensified into a pitch black environment. I became aware of the murmuring voices of other people who had groped their way in before me, but I was profoundly disoriented. How many people were in the space? Would I bump up against them? Would I panic? How large was the space? How would I escape?

I then heard the reassuring voice of my son Brad, who apparently had gone in long before me. He urged me to slow my movements and stay, even though it was a place so dark and disorienting that nothing—not a hand pressed against my nose, nothing—could be seen. Brad promised me that my eyes would eventually adjust to allow me to see forms. I stayed and, indeed, after six or seven minutes the darkness abated. I could see the outlines of people moving slowly through the space like specters.

The lighting had not changed, my perceptions had; and with this change, my psychological disorientation left. I became open to my intense awareness of my own being, but a being out of body—an absence within a void. When other people including Christina entered the space, I joined Brad in calming them. Soon we all became a community of bodies and voices, urging patience on new strangers to stay to the moment when their eyes again could see, even in total darkness, for they, like us, would have an unforgettable experience. Christina and I eventually left. Brad lingered on. To him that space of perceptual engagement with total darkness had morphed into a room inhabited by a community of human beings caring for each other, and he let himself be absorbed by those feelings.

I am not a religious person in terms of organized religion, but the experience did evoke the spiritual understanding of the body/mind oneness and the oneness of human community.

Schuld ends her catalogue essay with a summary especially apt to Orr’s work: “A phenomenal art enables us to observe how our knowledge of the world is shaped, not as an object but as an embodied experience with spatial and temporal dimension. With no specific object to which we might attend, we are left to consider the work in terms of the dynamics of perceptual engagement. Moreover, we take the work with us: our heightened senses, now attuned to the subtleties of the conscious fringe, encounter a more vivid world than the one we left behind” (p. 121). I agree, Orr’s work extends the limits of consciousness, and I will long remember the possibilities for calm—and oneness—that the encounter made me understand.

Later that evening we went out to dinner, shared margaritas and West Coast oysters, and planned our trip back to LA, by way of the Orange County Museum of Art in Newport Beach, California. The exhibition there, State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970, with its focus on conceptual art, will be the subject of Letter #4.

© Patricia Hills, 2012