Letter #2 from Southern California

Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980

By: Patricia Hills - Apr 05, 2012

In my Letter #1 I discussed my reactions to three of the LA exhibitions participating in the Pacific Standard Time initiative: The Otis Center of Art and Design, with its exhibition focused on the LA feminist movement and the Women’s Building; the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center in Santa Monica, which hosted the lead PST exhibition; and the Hammer Museum’s Now Dig This? Art & Black Los Angeles 1960-1980, an exhibition of mostly African American artists.

Day 2

The next morning was Friday, January 6, and my son Brad and I set out for Long Beach, south of LA. Our destination was my daughter Christina’s rented condo in Coronado, a suburb of San Diego, but my mission continued to be searching out those exhibitions funded by the Getty Foundation’s initiative Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980 and located along the 140-mile highway to San Diego.

It made sense to stop next at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach, with its exhibition MEX/L.A.: “Mexican” Modernism(s) in Los Angeles, 1930-1985. The goal of the very large exhibition, as stated in the foreword to the accompanying bilingual catalogue, by chief curator Cecilia Fajardo-Hill, was to present “a hybrid culture that has shaped multiple key aspects of Los Angeles art and culture.” The show itself was curated by Rubén Ortiz-Torres, a professor of Visual Arts at UC/San Diego.

A customized 1964 Chevy Impala, an actual automobile nicknamed Gypsy Rose, by Jesse Valadez, the “low-rider godfather” of East LA car culture, greeted the visitor at the entrance. We then entered a sprawling exhibition, with paintings, videos (clips highlighting stereotypes embedded in old Hollywood movies and Disney cartoons) photographs, and installations. Certainly we knew about Los Tres Grandes—Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco—all of whom came to the LA area during the 1930s, painted murals, and made an impact on local artists. And we knew about Tina Modotti’s photographs, although we didn’t know that she played in sentimental silent films (on view on monitors in the exhibition) before she met Edward Weston and took off for Mexico. We also knew of Yolanda López and Guillermo Gómez-Peña, who have had exposure in the East, particularly Washington DC and Boston. But have we heard of Alfredo Ramos Martinez, who painted in the 1930s? Or the more contemporary photographers Harry Gamboa Jr, Juan Valdez, Graciela Iturbide, and Ricardo Valverde?

The eight 1930s tempera paintings by Martinez, compare with Rivera in terms of powerful imagery; we should all know more about him. And it was a pleasure to see some of the studies for Orozco’s magnificent mural Prometheus (which I saw a few days later at Pomona College.) Not to discriminate, the exhibition curators also included 1960 studies by Rico Lebrun for his mural Horse of the Apocalypse (also at Pomona). Siqueiros was represented by a sketch for his mural América Tropical, a lithograph, and an oil painting of Zapata. The curators did not neglect Rivera, but his work appeared in a surprising context, which I will discuss momentarily.

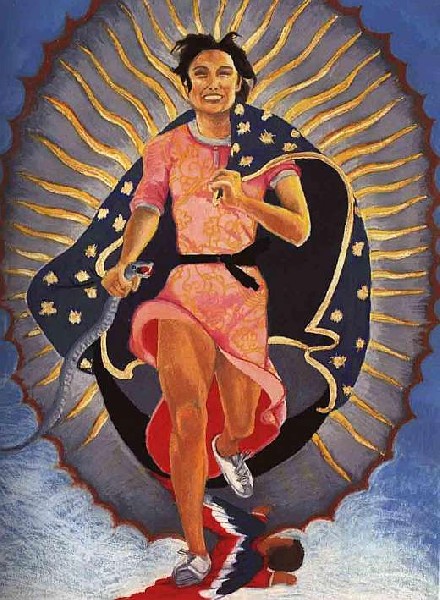

I was pleased again to see the original triptych that made Yolanda López famous: three large oil pastels that include portraits of her grandmother, her mother, and herself, in, respectively: Guadalupe: Victoria F. Franco; Margaret F. Stewart: Our Land of Guadalupe; and Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe, 1978. According to the catalogue essay by Catha Paquette, the artist included these three paintings in her MFA diploma exhibition for the studio department at UC/San Diego. An activist even then, López took a further step by organizing bus trips to take Mexicans and Mexican Americans from Balboa Park to the UCSD campus to see her exhibition that celebrated Chicana culture. This was in 1979, when the Anglo world by and large ignored the art of Latinos and Latinas.

I have always loved the image of an exuberant, grinning López springing forward from the Virgin of Guadalupe’s almond-shaped mandorla with a star-studded mantle draped around her. In her sprint toward liberation, López clutches a snake in her right hand and nearly tramples a winged cherub lying on the ground, as if declaring her right to borrow from the heritage of Virgin Mary imagery even when she rejects the piety.

The photographs in the exhibition commanded our attention, but not all the photographers could claim a Latino heritage. For example, 1950s color photographs by Paul Outerbridge, showed leisure activities of the vacationing Latino bourgeois businessmen and their families lounging at luxury hotel pool sides.

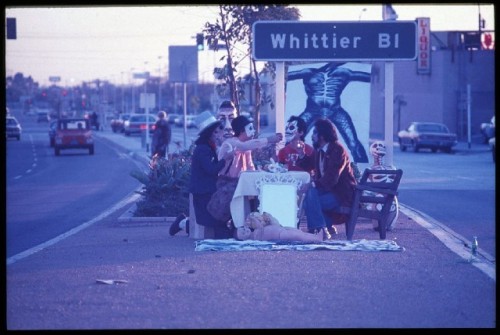

These set the stage for the gritty street photography of the 1970s and 1980s that were highlights of the show. Not exactly “street photography” of anonymous people in the sense of a Garry Winogrand or early Joel Meyerowitz, but full-length portraits of photographers’ friends standing on the sidewalks of their neighborhoods. As a group the photographs tell the story of the rise of the Chicano/a movement, from the images of the East LA “zootsuiters,” to the protests of the 1960s, and the street performance art of the 1970s. Harry Gamboa Jr., a photographer on the scene, participated in the founding in 1972 of “Asco” [Spanish for “disgust”] that included Willie Herrón III, Gronk (Glugio Nicandro), and Patssi Valdez [about whom Charles Giuliano has been writing]. The group performed in the famous Walking Mural, with Valdez as the Virgin of Guadalupe. Another performance (with garish masks and costumes) was First Supper (After a Major Riot) of 1974, when Asco set up a table and chairs on a traffic island next to Whittier Boulevard, the site of a 1970 anti-war demonstration and police riot. Gamboa was also on the scene in the late 1970s photographing César Chávez, more artists, and protesters. There was a lot to protest, especially the Chicano fatalities in the Vietnam War, bloody confrontations between the police and neighborhood people, and racism.

Other photographers demand mention especially for the ways they took control of the representation of their Latino neighborhoods. Juan Valdez did a series in color in the 1970s called “East L.A. Portraits.” Stunning, proud, handsome men and women pose outside—on the sidewalk, at bus stops—for the photographer. Graciela Iturbide’s series focused on the White Fence barrio of East LA in the mid-1980s and included glamorous young moms posing casually outdoors with their babies. Ricardo Valverde altered photographs (with a date range of 1978/1993) take on a surrealist tone, when he cuts, scratches and adds elements such as black dots and white bands to mask the eyes of his working-class Mexican subjects. The subjects are compelling, but I’m not sure what they mean.

The film and video components of the exhibition highlighted the stereotypes of Mexicans that have persisted in the last century. Disney Studios caricatured Mexicans in featured cartoons, such as The Three Caballeros, which depicts Donald Duck and his pals as guitar-thumping, grinning, Mexican singers wearing outsized sombreros.

Most intriguing, however, was the presence of Diego Rivera’s painting, The Flower Carrier, 1935, the original of which measures almost four by four feet, that hung as a reproduction in several B-movies of the early Cold War period and apparently served as a trope for “evil” doings, such as sinister Communist Party machinations. A monitor carried segments of the films Bury Me Dead, 1947; Where There’s Life, 1947; I Married a Communist I (also called The Woman on Pier 13 and Beautiful but Dangerous), 1949; In a Lonely Place, 1950; and The Prowler, 1951. Naturally I spent some time looking at the movie clips of living room interiors where reproductions of Rivera’s picture functioned as plot clues to underscore the dastardly intentions of villains conniving nefarious schemes. It mystifies me why a Hollywood director or set stylist would see the Rivera painting as a potent symbol of evil, except that Rivera was a well-known Leftist.

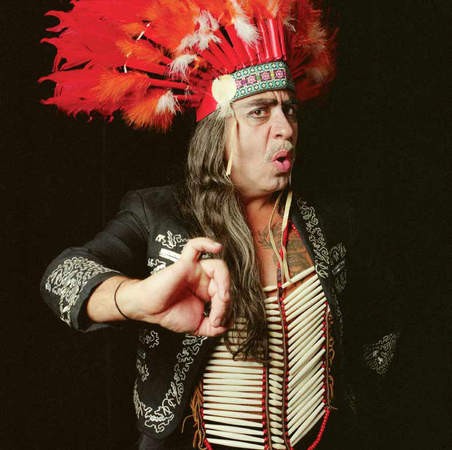

Finally, near the end of the exhibition was a table set up with props that Guillermo Goméz-Peña used in his installations. Does anyone remember his performance at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, on the occasion of the exhibition The Bleeding Heart in 1991. He was funny, shocking, and riveting, as he used his own body as a site from which to harangue his audience about Mexican stereotypes. Later he and Coco Fusco created the performance piece, Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West (1992-94), in which they put themselves in a 10 x 12-ft cage as exotic creatures. Created at a time when there was much hoopla over the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s “discovery of America,” the two artists brought the needed irony to the “celebrations.”

Later it occurred to me that what was missing from MEX/L.A. were examples from the Chicano mural movement, particularly references to those murals on the outside walls of the Estrada Courts Housing Project in East LA, and also the work of Judy Baca, founder of the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC), who along with students created the Great Wall of LA in the 1980s. When I emailed the curator, Rubén Ortiz Torres, he explained that he had no intention of presenting “a comprehensive history of Chicano art” in LA.

He wanted his exhibition to look forward not back, meaning that his focus was not the continuity of tradition, but the ways much East L.A. art of the 1960s-1980s disrupted conventions and set the stage for future art. Indeed, the artists Lopez, Gamboa, and Iturbide reclaimed their heritage but asserted their rights to control their own discourse, subjectivities, and representation. To me, they succeeded, and their images look fresh today.

In sum, I liked the show at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach. I learned from it and envied the Southern Californians who have such vibrant artists working in their midst. New England art seems pale by comparison. My next letter turns to the light and space works in the exhibition Phenomenal: California Light, Surface in the two San Diego Museums of Contemporary Art, both in downtown San Diego and out in La Jolla. Those exhibitions touch on the Apollonian sublime – with none of the Dionysian boisterousness of the Long Beach exhibition.

© Patricia Hills, 2012

Letter Number One