George Wein Part One

From Boston's Storyville to Newport Jazz Festival

By: Charles Giuliano - May 02, 2011

In the jazz world the legacy of George Wein (Born October 3, 1925) is unprecedented.

We spoke with him recently while in the process of preparing for another season of jazz and folk festivals. Two years ago he transformed the historic Newport Jazz Festival into a non-profit in the hope that it will sustain after he is gone.

This is the first of three installements. It is a part of a series of dialogues with seminal arts leaders in the cultural history of Boston from the 1950s through the present.

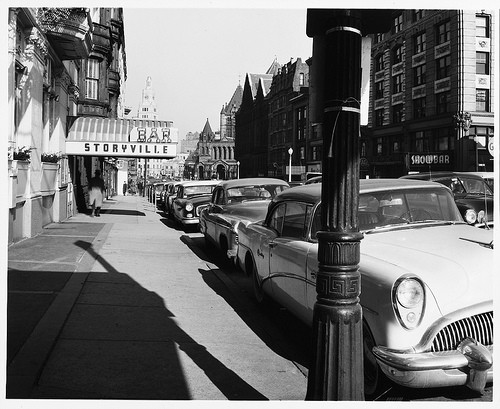

Before Newport, Wein, who grew up in Newton and attended Boston University on the GI Bill, ran a legendary jazz club in Copley Square called Storyville.

George Wein You’re right on time. In fact a minute early. What can we do for you?

Charles Giuliano When I was a teenager, my Uncle James Flynn, took my sister and me to Storyville to hear Duke Ellington. It was my first exposure to live jazz.

GW A good beginning.

CG As I recall the club was painted in black, brown and beige.

GW Yes.

CG In addition to Storyville of course I would like to talk with you about the Newport Jazz Festival, what is happening now. As well as the collection that you and Joyce assembled of African American artists. Particularly as that work has been shown at Boston University and some pieces have now been donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

There is a lot to talk about.

How are you?

GW I’m fine. Getting a little older every day Charlie. I’m in good health. Working very hard and pleased with what I have done with the Jazz Festival this year. The Folk Festival is going gangbusters.

CG I understand there was a tough transition going back to Newport.

GW There was an incident at Newport in 1971. That was two years after Woodstock. It was the era when music should be free. We had 20,000 people in the park and another 8,000 to 10,000 outside trying to break the fences down which they managed to do. We sent the 20,000 people home and then we were out of Newport for ten years. That’s when I started the Festival in New York, in 1972.

CG I reported on that for the Boston Herald Traveler.

GW You reported on the kids breaking the fence down.

CG It ran on the front page of the Sunday Herald Traveler. Ernie Santosuosso in the Sunday Globe ran a review of the concert which never happened.

GW I remember you well from those days. You were always a good friend.

CG What I am referring to is actually more recent. Wasn’t there a two year lapse?

GW What happened is that I sold my company four years ago. I was still involved in producing the festivals. I was on a salary with the people. But after a year and eleven months they went busted. I had sold them the name the Newport Jazz Festival. But I had a clause in that contract where it came back to me if they went out of business, or abandoned it, or went bankrupt. They abandoned it so I just went back there by myself and took it back. We had two great years. We had a sponsor that made it possible to get by for two years both the Folk and the Jazz.

This year I made the major decision to go non-profit. Going back after I sold it made me realize that I would like to perpetuate it. These events should continue after I’m gone. The only way to do that is to go non profit and then get people involved. People willing to support it. So I’m putting a lot of my life’s earnings into it and asking people to join me. If they do the festivals will go on long after I’m gone.

CG I was talking with John Sdoucus who sends his regards.

GW John is a good friend of many years.

CG He told me that when that occurred you told him you were going to “put every penny I have into making that happen.” If necessary.

GW Well, yes, I’m going to put a lot of money into it if I get help. I’m working pro bono. I can’t take a dime out because I’m putting money in. That’s no problem. Thanks God. I don’t have to make a living out of the festivals. So that means that the profit motive is not as strong as when I was supporting a whole business doing jazz events all around the world.

CG So you sold the entire business and not just Newport.

GW I sold the entire business. But I don’t want the entire business. I just want Newport that’s all.

CG Newport was a brand.

GW Newport is my legacy. It’s a brand that goes with my name.

CG When you went to New York, initially, wasn’t it the Kool Jazz Festival?

GW When I went to New York it was the Newport Jazz Festival New York. We have a license on the name Newport and kept it alive. It became the Kool Jazz Festival but produced by the Newport Jazz Festival. We always kept the logo in there somewhere.

CG Is there a sponsor this year?

GW We have two sponsors. Alex and Ani a jewelry company from Rhode Island which will make symbolic pendants and wrist bands which they will sell at the festival. It’s a young people’s thing. They are going to be very successful. Not a major sponsor but a good local sponsor. There’s another company getting ready but I don’t want to give the name because the contract’s not signed.

CG Can we go back to Storyville. You were a nice Jewish kid from Newton playing the piano and going to Boston University. How the hell did you open a night club?

GW In those days you could do things very cheaply. I didn’t have any money. I had $5,000 that had been given to me for my education. I didn’t use it because of the GI Bill. The Army paid for my four years of education. I leased a room from a hotel. In those days you could buy tables and chairs for ten dollars. A cash register for sixty dollars. A piano for $600. So $5,000 went a long way in those days.

CG You started at the Buckminster in Kenmore Square, right.

GW No. The first one was in Copley Square at the Copley Square Hotel. When I found out the guy was cheating me on the liquor I closed up and went to the Buckminster. I was there for three years and then I went back to the Copley Square Hotel.

CG It is good to clarify this as people have been telling me it started at the Buckminster.

GW No it started in what became Mahogany Hall. I did two rooms Storyville and Mahogany Hall. What was the original Storyville. Down stairs, I called Mahogany Hall. I had the big names upstairs and the Dixieland downstairs. I opened in the fall of 1950 in Copley Square. I closed after six weeks and opened up in January or February of ’51 at the Buckminster. I think in ’53 I went back to the Copley Square Hotel. I was there until 1960. That’s when I moved to New York. I was doing production and management. I was producing festivals. The management at that time was Albert Grossman who was managing Peter, Paul and Mary and then Bob Dylan, Odetta. He was my partner and I was producing the Jazz Festival and the Folk Festival. I had a partner in Detroit. We did a festival in Detroit.

Then there was the riot in Newport in 1960 and we all ran out of money.

As Marc Myers has reported “But what began as a chance to swim, find romance and listen to live jazz quickly turned ugly on the evening of Saturday, July 2. Unable to disperse an intoxicated mob of up to 12,000 young people seeking access to the sold-out Newport Jazz Festival, New England's wealthiest community summoned the state police and then the National Guard to restore order. When the tear gas cleared, stricter rules for crowd control and alcohol consumption were enforced at outdoor jazz, rock, pop and soul concerts nationwide. And the Newport Jazz Festival was left with a black eye.”

Then I started working overseas to make a living.

That was the first time the Festival was finished. I went back in 1962. By myself. Then I had another incident in 1971. That’s when I went to New York. ’71 was the Music Should Be Free situation. 1960 was the beer kids. We never had a riot in the Festival. It was always outside. The police in 1960 asked me to keep the music going until two in the morning so they could clear up the streets outside. I had all the musicians extend their playing so they could clean up what was happening. So many people came to town because they kept the bars open until four in the morning.

CG Let’s go back to Copley Square. What was a jazz scene at that time and what was your motive to get involved?

GW My roots were at the Savoy where they would keep a band for six weeks. Usually a traditional band of some sort. I had Bob Wilbur (reeds), Sidney DeParis (trumpet), Sid Catlett on drums. It was a very nice band. When I went to the Buckminster I did the same thing. We weren’t doing much business. Then we closed for the summer.

Somebody sold me George Shearing for $2,500 a week. It was a fortune. We sold out the entire ten day engagement of George Shearing. You couldn’t get in the club. That’s when I realized I had to play different attractions and play bigger names. That’s when I got involved with everything in jazz from Charlie Parker to Lennie Tristano. Charlie Parker played Storyville twice.

CG As a kid I remember seeing an ad for Billie Holiday. I wanted to see her.

GW Yeah we had Billie Holiday. As well as Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong. Everyone played there. You said you saw Duke there. He played several times.

CG During the summer you ran a club in Gloucester, Mass.

GW Yes, we used to close during the summer and go up to the Hawthorne Inn in Gloucester. There was a fire there at the Hawthorne Inn.

CG My family has a summer home in Annisquam so as a teenager I went to the Hawthorne Inn several times.

GW We had fun. We used a traditional band up there. Charlie do you have my book? Myself Among Others, a Memoir. It has a lot of what you are asking. You can check the answers.