Jazz Entrepreneur George Wein Two

Storyville to Newport

By: Charles Giuliano - May 03, 2011

Charles Giuliano What was your motivation for going into the jazz business? You started the nightclub Storyville early on.

George Wein I never had a motivation. I was going to college. It never entered my mind to have my own nightclub.

CG Where were you playing piano?

GW At the Savoy and at the Ken Club. All the time I was in college (Boston University) I was often playing seven nights and Sunday afternoons. My senior year I arranged classes so I only had them on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. So I could sleep Tuesdays and Thursdays. I was part of the jazz world and jazz was my life. I never thought about being a musician or going into the business of jazz.

When I got out of college I went to my grandfather’s business and asked him for a job. But they didn’t have one for me. It was a paper products business. They were distributors. So I said the hell with it and took a job playing piano in a Chinese restaurant. Somebody came to me and said why don’t you start your own club? It was never a motivation but I was in the world of jazz and music was my crutch. That was my excuse for not getting a job.

CG I remember you playing during intermissions.

GW I didn’t play that much when I took over the club. But I would front bands and play outside the club. First I had the Storyville All Stars and then it became the Newport All Stars.

Newport happened because of Storyville. I never had the motivation to do a jazz festival per se. When the Lorillards (Louis and Elaine) came into my club (1954) they said we would like to do something in Newport for the summer. I came up with the idea of a festival because Tanglewood had a festival. A classical festival. So why couldn’t we have a jazz festival. The first year it was held at the Newport Casino.

CG A Stanford White building.

GW Yeah, it’s still there and we are still doing things every Friday night during the festival. Then the Lorillards got divorced. They supported it for the first several years. Until 1960 when we had that first riot. The Beer Can Riot we call it because the kids were throwing beer cans at the police. The Lorrilards got divorced. There was nothing in 1961. Then in ’62 I said, nobody is doing anything so I’ll go back there. I called some friends and raised a little money and went back. That’s been my life ever since. I did not know I was a pioneer. We were just doing things. We created the first jazz festival at Newport. Then, when we came to New York, we created the first urban jazz festival.

When we came to NY we used Carnegie Hall, Avery Fisher Hall, Radio City Music Hall. We had 40 events in ten days.

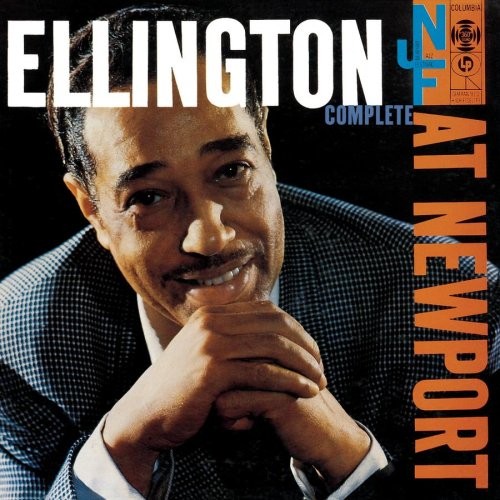

CG Can we talk about the most famous night at Newport in 1956 with Duke Ellington and Paul Gonsalvez.

GW Duke called me the night before. There was a party in Newport and somehow he got the number. It was at the Lorillard’s house. He said “What’s happening up there?” I said “What are you planning on doing?” He said “Well the medley and then a few things.” I said “You better come in here swinging. The critics are out to get you unless you do something.”

CG Why would the critics be out to get him?

GW The critics in those days were very involved in criticizing everything that happened. It was a brand new situation to have a brand new festival with every major artist. Everyone had a game. It was really the beginning of major jazz criticism. Up to then there had just been Downbeat and Metronome. Then came John Wilson in the New York Times. It’s probably why you were assigned to cover for the Boston Herald Traveler later on. We were the establishment. So they didn’t want Duke playing the same medley he played everywhere. He needed to do something new, something different.

CG He introduced the Festival Suite.

(Personnel: Duke Ellington (piano); Ray Nance (vocals, trumpet); Jimmy Grisson (vocals); Russell Procope (alto saxophone, clarinet); Johnny Hodges (alto saxophone); Paul Gonsalves (tenor saxophone); Jimmy Hamilton (tenor saxophone, clarinet); Harry Carney (baritone saxophone); John Cook, Clark Terry, William "Cat" Anderson (trumpet); John Sanders, Quentin Jackson, Britt Woodman (trombone); Jimmy Woode (bass); Sam Woodyard (drums).)

It was not that well received.

GW No but then there was the Gonsalves solo on “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue” which was the most fantastic thing he had done in years.

CG Also George Avakian of Columbia recorded the festival and that was a break through to issuing live music and expanding through LPs from the traditional three minute cuts.

GW Columbia said “We want to record” which was a big thing so I said, “Ok you pay the artists.” So I would get the artists for nothing which I thought was a really good deal. They paid Duke that night. But it was a bad deal. We should have gotten royalties on the records. We never got royalties. I forget but I was probably paying Duke five or six thousand dollars for the night. I can’t remember the prices in those days.

CG Didn’t you have your own Storyville label?

GW I had a little company for awhile. Two or three years. But I wasn’t in the record business.

CG You recorded Vic Dickenson, Ruby Braff, Wild Bill Davidson.

GW We had about 20 different albums. Jackie Cain and Roy Kral. Ruby, and Pee Wee Russell.

CG Those were 10” LPs.

GW They started with 10” and ended up with 12.” Then we let it go.

CG Do you think you should have stayed in the record business?

GW No unless I just wanted to spend 24 hours a day making a living grinding out records. You can’t do things part way. I tried management. I managed Teddy King and Jackie and Roy, and a few other people like that. Then I realized you can’t do both. I ended up giving my life to what I do best which is producing festivals.

CG You are notable for having married an African American woman and been so involved in African American culture. That was very unusual for the 1950s.

GW It’s difficult to read people’s minds. There were different attitudes. One was it was very liberal and isn’t it wonderful. To have the courage to marry an African American girl before the Civil Rights Bill. Another thing was people saying why are you taking one of our best girls when we can’t have any of your girls? Black guys would say that to me. Everything is a different attitude with different people. Some people resented the integration while others loved the thought of integration. My white friends, close friends supported me and they loved Joyce. Other people, I don’t know what it cost me, I don’t think it cost me anything because the pluses far outweighed the minuses. The best thing I ever did in my life was marry Joyce. That was the best thing I ever did.

CG Think about how early that was.

GW We married in 1959. The friends that we made had kept me going. The help that we received. From both the black and white communities.