Edith Wharton at Home: Life at The Mount

A Study by Richard Guy Wilson With Photos by John Arthur

By: Charles Giuliano - May 07, 2013

Edith Wharton at Home: Life at The Mount

By Richard Guy Wilson

Foreward by Pauline C. Metcalf

Photography by John Arthur

The Monacelli Press, 2012

188 pages, illustrated, with index and notes

ISBN 978 1 58093 328 5

US $45 Canada $51

Images for this article courtesy and copyright of John Arthur C., 2012

In an absorbing manner “Edith Wharton at Home: Life at The Mount” combines the insightful detailed scholarship of the distinguished architectural historian, Richard Guy Wilson, a forweard by Pauline C. Metcalf, and the superb photography of John Arthur. The book provides a compelling and often poignant narrative.

More than a study of architecture Wilson probes deeply into an understanding of Wharton, the complexities of her failed relationships, and the evolution of her advanced approach to structure and design as well as how that conflated with her style of narrative fiction.

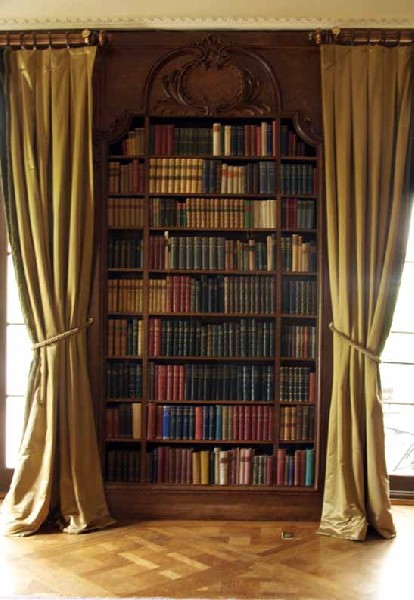

The summer home of one of the foremost American authors of her generation The Mount was an exquisite expression of unique ideas formulated and published in collaboration with Ogden Codman (1863 – 1951) as the seminal treatise of its era “Decoration of Houses” (1897).

With a move from Newport, Rhode Island, Codman was the obvious choice to design the ambitious Lenox home of Edith (1862 – 1937) and Edward R. (Teddy) Wharton (1850-1928). As Wilson lays bare with scathing intensity the audacious Codman was not about to reduce his handsome fee for a colleague, collaborator or “friend.”

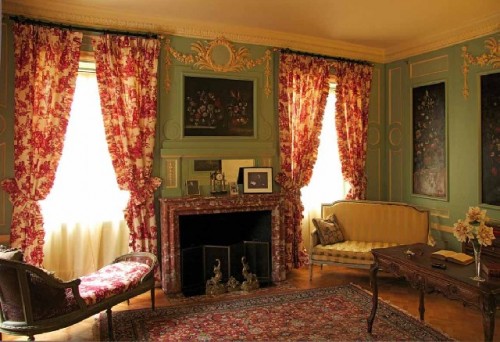

Although she was involved in every aspect of the design the architect of record was the more affordable Francis L. V. Hoppin (1867–1941). The Mount's main house was inspired by the 17th-century Belton House in England, with additional influences from classical Italian and French architecture. The Whartons later met Codman’s price to design the interior details according to her wishes.

Wharton's niece, Beatrix Jones Farrand, designed the kitchen garden and the drive. Farrand was the only woman of the eleven founders of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Codman gossiped about his famous collaborator in letters to his mother. Wilson has quoted from this correspondence as evidence of the manner, perhaps all too typical of the period, in which Wharton was abused by men she loved and admired.

As a woman of letters, however, she held her own through great adversity, both personal and professional, which earned her fame and fortune. Her novels were best sellers later relegated to a lesser status as period fiction focused on the lives of the very rich and privileged. After a later scholarly reevaluation Wharton is regarded today as a leading American author of her generation on a level with her great friend Henry James.

The Wharton’s built and owned The Mount from 1902 to 1911. They lived and entertained in their home from June through Thanksgiving with travel to Europe the rest of the year.

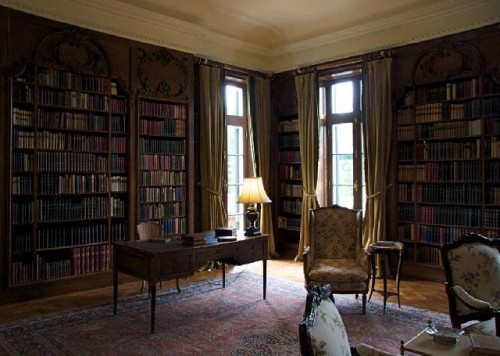

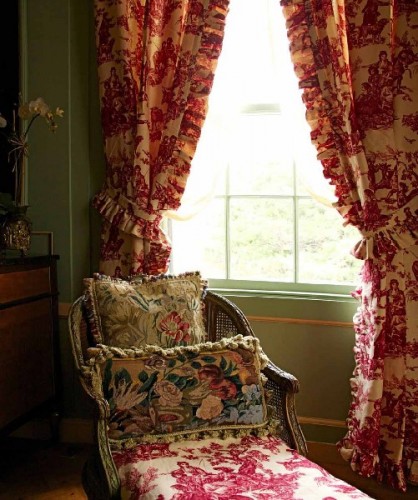

As Wilson analyses The Mount it was designed around providing her privacy in a suite of rooms that allowed for work without interruption while entertaining guests who stayed for weeks and even months at a time. The suite for Teddy, who did not share her literary and artistic life, adjoined hers with his dressing room.

Unlike the pompous and pretentious Newport cottages with their grand balls and intensive social calendar The Mount was designed for comfortable country living and casual entertainment. The dimensions for dining, for example, were intimate and modest by the standards of The Gilded Age.

The Whartons were well off and socially connected but more through her wit and talent than deep pockets. Teddy, whose physical and mental health declined, relied on her income which he controlled, speculated on with losses, and embezzled.

Even by Berkshire standards, compared to those of Newport, the Whartons lived well but were of modest means compared to many of their neighbors. The Whartons who entertained at home did not have the challenge of keeping up with the Joneses. Their guests were more often artists, like Daniel Chester French who lived nearby, and writers rather than captains of industry and finance. Their social life was chronicled by Berkshire gossip columnists whom Wilson uses as a resource.

With a combination of saddle horses, Teddy had several and looked after the stables, and carriages, they enjoyed riding about the Berkshires exploring its hamlets. Oddly, she was critiqued for not knowing the terrain she described in “Ethan Frome” (1911). In fact she knew the Berkshires intimately. When they acquired a car and driver (Charles Cook) in 1904 they traveled as far as Beverly, Vermont and Newport.

Cook continued as Wharton’s driver in France including visits to battle fields where she did relief work. In 1921 he suffered a stroke and returned to the States with a pension from Wharton. Typically, she was most generous to their servants. She worked with staff not only in management of the house but also the extensive grounds. The initial head gardener was an incompetent drunk replaced by one she could work with.

When “House of Mirth” was published in 1905 it sold 140,000 copies between October and the end of December, It was her first successful novel and by 1911 when she left Lenox never to return she was assured the steady income of an established author. In fact, she was the best selling American author of her era.

As Wilson conveys there was an intimate relationship between Wharton’s knowledge and passion for architecture, landscape, and interior design and the role that plays in her literature. There is enormous detail and pride of place in the manner in which Wharton set down her characters and described their actions.

Consider, for example, the role of city planning and the urban settings in "The Age of Innocence" (1920). It captures the mood of New York during a time of its development when The Dakota, constructed from October 25, 1880 to October 27, 1884, located on the northwest corner of 72nd Street and Central Park West in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, was so named for its daunting distance from civilised neighborhoods.

Or how the Cottages of Newport figure into the narrative of "The Buccaneers" which was unfinished at the time of her death in 1937.

Which is why The Mount is more than just a great American home in which a famous author resided. Not just a shrine and pilgrimage destination for her many global fans to visit and spend time in The Mount invites us truly to imbibe of her spirit and originality.

Arguably, there are only a few American architectural destinations quite like The Mount. It compares, for example, to Jefferson’s Monticello where one imbibes the genius of a great man of the Enlightenment. The grim Hermitage of Jackson with its slave quarters. Or the shockingly cramped Eisenhower home on the campus of the first Presidential Library with its many siblings in Abilene, Kansas.

The Mount as a paradigm is far more subtle and nuanced. Like her novels it takes time and patience to unravel its mysteries and conundrums. Turning and twisting about in the house I have found myself confused and confronted by its odd design decisions. Like the back or main entrance, talk about ambivalence, in which one enters not to a vista but rather an ersatz atrium or galleria that shunts us off, with a bit of statuary, to an entrance leading to stairs to the floor above and another galleria.

The “back” of the house leads to a terrace overlooking the formal gardens and a lake beyond. From the gardens and their privacy we have the best views of the grand house. By turning its back to visitors, so to speak, the strategy of the villa is just the opposite of the ostentatious display of wealth in the Newport cottages.

Actually The Mount is not visible from the road. Vistors first approach the Gate House, which housed servants, as well as the great barn which also quartered Wharton's staff. Both buildings are being renovated. The Gate House will be a research center with accomodations for visiting scholars. The office which is presently there will be moved to the renovated stables which will be developed as a performing arts center.

If one gained access to The Mount there was a drive or scenic walk to the house itself. Deliveries would be received within the walled courtyard with no disruption of the occupants of the house.

This space was used well during last year's WordFest where a large tent was erected for programming. It is where panels and speakers were heard while up on the porch there were simultaneous readings and performances of music.

Following Wilson’s analysis this distancing design strategy had the advantage of slowing down visitors requiring them to be received and announced rather than barging in and disturbing her solitude and work.

These design elements start to make sense over the course of repeated visits to The Mount on occasions both public and private. We have explored servant and guest quarters not open to the public; and clambered up to the roof with its cupola for panoramic views of the gardens.

Over time, as a regular visitor to The Mount, slowly but surely Wharton seeps into you. It becomes visceral. That explains why it was no House of Mirth and has evoked so much passion and pain. Teddy, as the last straw of their failed relationship, sold it without her knowledge while she was on the high seas seeking a new life in France.

In 1909 and 1910 The Mount was rented to Alfred and Mary Shattuck. In July 1911 the Whartons stayed at The Mount. Henry James, a guest, left hurriedly when “violent and unjustified abuse” took place. When Edith left Teddy had “power of attorney” to negotiate a sale but not without her approval. The Mount which had cost $250,000 he sold at a loss for $180,000.

It was owned by the Shattucks and their heirs until 1938. Prior to that, in a 1935 auction, the contents of the house, including what had been owned by the Whartons, was sold. During the height of the depression the estate was sold for $25,600 to Louise and Carr V. Van Anda. He was then the managing editor of the New York Times.

In 1942 the house and 155 acres were sold to Aileen M. Farrell for $18,000 with another $5,659 for the contents of the house. It was joined with the abutting former Westinghouse estate Erskine Park to expand Foxhollow School which Farrell founded.

Between 1972 and 1976 the house remained empty and suffered considerable damage. By then, other than walls, the gardens were no longer visible. In 1971 The Mount was declared a National Historic Landmark.

Farrell set up a Committee for the Restoration of the Mount. There were grants but never enough adequately to maintain the deteriorating property. Shakespeare & Company rented The Mount from developer Donald Altschuler in 1978. In 1979 Edith Wharton Restoration was established. For a time the two organizations pursued very different missions leading to an inevitable separation.

Shakespeare & Company acquired a campus in Lenox. Not that long ago both The Mount and Shakespeare & Company faced bankruptcy. Since then they have achieved some fiscal stability through fundraising and restructured debt. (Interview with director Susan Wissler)

This summer S&Co will symbolically return to The Mount for an outdoor production of A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Under a former director a decision was reached to purchase Wharton's original library. It was viewed as essential to restoring her heart and soul, the books that she read and annotated, to the estate. The debt came close to breaking EWS. Now, however, having come back from the brink of extinction, it is described as one of The Mount's greatest attractions.

Wags comment that the books were enormously overpriced and a better deal was not negotiated. A collection of leather bound period volumes would have served the bill at a fraction of the price. This is consistent with the fact that The Mount, like Monticello, contains none of the original furnishings. Because there are no surviving detailed photographs of all of the rooms it is argued that some of the interior decoration is pure fantasy.

While there continues to be debate among scholars and journalists the Wharton spirit and legacy prevails at The Mount.