Matuschka, Artistic Activist, Activist Artist

Another Vintage Interview

By: Edward Bride - May 21, 2013

Serving two masters, as the saying goes, means that you serve neither well.

On the other hand, dueling priorities can sometimes be symbiotic: Feeding one actually nurtures the other. In the long run, being able to thrive where one achieves two claims to fame can be a notable achievement.

Such is the case with Matuschka, the one-named artist whose reputation as an activist preceded her fame as a fine-art photographer, model, and abstract artist. In fact, it could be argued that she achieved success as an artist because she was first known (better, at least) as an activist.

Well-known as an avid campaigner for breast cancer awareness, Matuschka would rather be known as an artist who became an activist out of necessity and a desire to help others. Her work is certainly worthy of such attention, since she has been an exhibiting artist since 1972, having her first solo show at the Lenox Library.

Nonetheless, the two aspects of Matuschka’s work have been so interwoven that it might be impossible to determine cause versus effect. From the 1970s to now, “it was just one evolution, and I guess I got lucky that something happened and I received recognition for some part of it.” Just as happens with political causes that are fostered by actors and other famous people, without her accomplishments in art, her voice as an activist might never have been heard.

At the same time, and unlike actors who campaign for causes, her activism was expressed within her art itself, and did help call attention to it; so perhaps there was a sort of symbiosis between her two personae. “I could have gone on, perhaps some day more known as an artist, but the activism did kick in,” so these two elements are, indeed, more connected than merely by passion or opportunism. Her fame provided a bloody pulpit, but the activist and the artist are one and same.

Evidence abounds: In 1993, Matuschka received the Rachael Carson Award for her work addressing environmental concerns. Her poster “Time for Prevention,” which was commissioned by Greenpeace, won the Best Environmental Poster of 1996. Many of her images addressing the breast cancer epidemic have been collected by museums and reprinted in a wide variety of publications, including the covers of the New York Times Magazine, McLeans, German Max, Professional Photography and FOTO, among others. In 1994 she was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and won numerous awards including a Front Page Award from the Newswoman Club of NY and a Gold from the World Press Foundation, one of the most prestigious awards in photography.

Very little of Matuschka’s contemporary work would fall into the activist category today. History is prologue, and some of Matuschka’s past has a more direct bearing on how she got to where she is today: a part-time Berkshires resident who is becoming more involved in the very ripe art scene in Pittsfield. She expects to be involved in curating shows; participating in the “Think Pink” exhibition in October to boost breast cancer awareness; the Artscape committee; and some formal affiliation with the Storefront Artist Project, starting with a solo show this Fall (or nearly solo: it will be mainly her work, with guest metal pieces by artist/sculptor and co-conspirator Zachary Ronan of Lenox).

Having lived in Lenox as a youth, being in the Berkshires is like finally coming home, she says. She enjoys the scenery, community spirit and the safe warm vibe of the area, remarkable given that she has lived in South Philadelphia, Arizona, France, England, California, and New York. This is the area where Matuschka feels most at home.

She considers the Berkshires “the friendliest place, where people actually call you back….” Besides which, “It’s gorgeous, friendly to the arts, close to New York and to Boston.”

She came to Lenox the first time in 1971 as a ward of the state of New Jersey, having moved among foster homes after her mother died and the courts decided it was best to remove her from her father for a variety of reasons. Windsor Mountain School, on West Street in Lenox (in spaces now occupied by the Berkshire Country Day School during the regular academic year, and the Boston University Tanglewood Institute in summer), was more-or-less a last chance for her, although the idea of a boarding school certainly wasn’t a big hit with this pre-teen future artist.

The school originally existed in Germany, a private prep school that moved to the Berkshires when Hitler came to power. In western Massachusetts, the student body was a wild mix, “bizarre,” as she says. There was a combination of wealthy children, kids whose parents were rock stars, famous actors and actresses, and then there were the disadvantaged youths from Harlem, who attended under a program called ABC, for “A Better Chance.”

Then, there was Matuschka, who fit none of those categories. She was legally an orphan, several unsuccessful adoptions or assignments to foster homes didn’t work out and in 1971 this wayward teenager was a ward of the state, and officially homeless. The Bureau of Children’s Services had no other option but to send her away. “I was being kicked out of the State of New Jersey,” Matuschka reflects, and sent to “bore-ing school,” a decision which “ironically turned out to be miraculous.”

Academically accomplished and with an art portfolio, Matuschka didn’t quite fit in, and yet her work stood out. She had doodled and drawn cartoons as a child, and was encouraged to take formal drawing classes by one foster mother whom she remembers fondly. “Mrs. Marco would leave a stack of art books on an end table outside my bedroom door. Every day there was a new selection. It was better than Christmas.” The books and classes brought a renewed inspiration to art, and set a behavior pattern that would last for the rest of her life: “My car is always loaded down with books.”

The Berkshires was already the arts and cultural mecca of the universe, as she remembers. It was the time of Arlo Guthrie, James Taylor and Alice’s Restaurant. The Music Inn. Tanglewood. And Mundy’s, “where everyone spun down over beer and a few rounds of pool.”

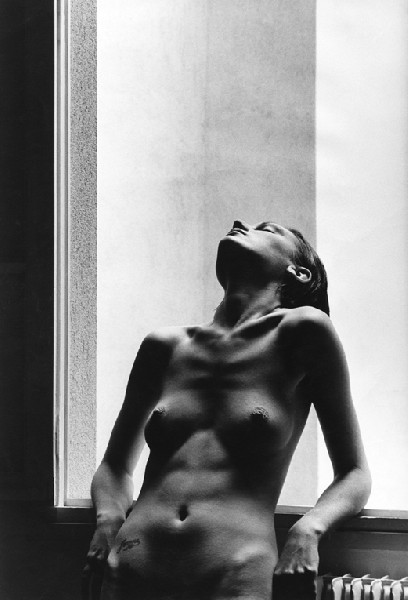

Before her scholastic stint here, Matuschka had put her toe in the arts water by becoming a model for life-sketching classes, which she says is a great foundation for all artists. Once again, this was advocated by her foster mom who knew she could make some money while watching others draw her. On breaks, she would walk around the class, see what the students were sketching, and of course hear what the teacher was saying. “It was two for the price of one. I got paid for modeling and received an education vicariously. “

She put that same ethic to work here, with the weekly drawing classes at Clemens Kalisher’s studio in Stockbridge, with Julio Grande teaching at BCC in Pittsfield, as well as with other regional artists. “Anybody famous --- or working as an artist- and who was showing here, I became their model,” she says. The aspiring artist took up residency on West Street, setting up a mirror in her basement apartment, applying the lessons that she had learnt in the daytime, and drawing herself.

Two years later Matuschka was accepted into George Washington University’s art school in St. Louis, but the idea of a big city turned her off, after falling in love with the pastoral setting of the Berkshires. Instead, she went on to Prescott College in Arizona, which almost immediately, and coincidentally, went bankrupt.

Returning east, she enrolled in the School of Visual Arts in NYC (which was also attended by Peter Dudek, new acting director of the Storefront Artists Project). She stayed there for a year; having satisfied all her academic credits at other schools, the only thing she needed at the School of Visual Arts was the art courses themselves, and she was already painting beyond her academic peers. Bored, she left, and went “freelance all the way,” as she puts it, never succumbing to a full-time job but taking on modeling assignments while perfecting her skills in the darkroom.

The sketch artist turned model absorbed instruction. Once in NYC she continued studying photography with ex-Berkshirite photo master Don Snyder, becoming more competent with chemically toning photos in the darkroom, and so has developed skills in all aspects of this particular visual art, from the true-to-life figuratist to abstract to photo adaptation and montage.

Nude modeling led to clothed modeling, and that led to fashion, sort-of a side-step. At the School of Visual Arts, she actually abandoned the figurative work, which she found too traditional, too commonplace. She discovered that she preferred modern, abstract art. Living on “museum row” in New York, she could walk to the Guggenheim, the Metropolitan, or the Whitney in a matter of minutes, so she was not lacking for inspirational surroundings. “That’s when I fell in love with abstract art.

“At the age of 20, I was painting large abstracts when I got waylaid into modeling, I’m not sure if I look at this time as wasted, but while I was modeling I became more and more interested in photography.” That part of her career progressed from taking Polaroid pictures and doing caricatures to still posing for fashion and nude photography, to becoming her own photographer. “I didn’t like the way I was looking in most of the photographs shot by other photographers, and figured I could do it differently. I’d look in the mirror, then gaze back at the contacts, and wonder ‘what happened here?’”

So, Matuschka decided to photograph herself.

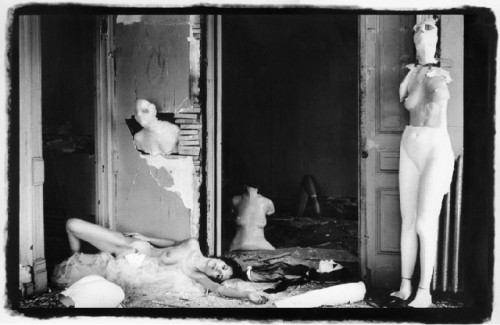

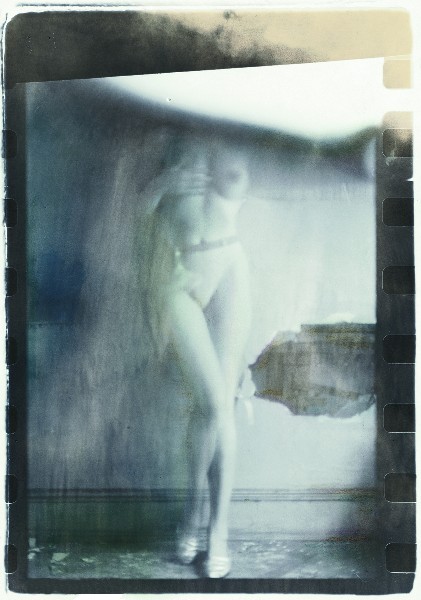

In 1987, she started a significant (for more ironic reasons) photographic project called the Ruins, for which images became prominently displayed in magazines and exhibited worldwide. Matuschka would photograph herself inside old abandoned buildings, among plaster casts of her own body or simply alone, clothed or otherwise. “It was a big production, moving all these plaster casts of myself to various locations, then setting up the lights and tripod, and jumping into the shot.”

Then in 1991, she got breast cancer which not only changed her life, but her work forever.

Fast-forward ten years.

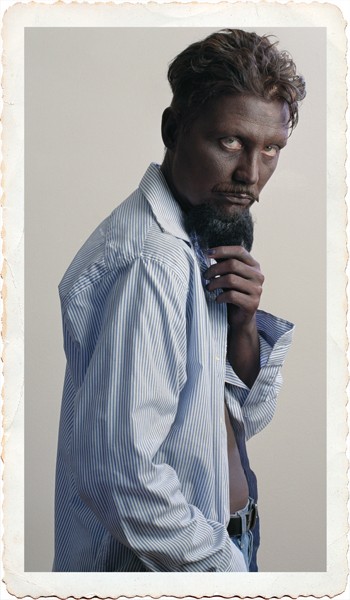

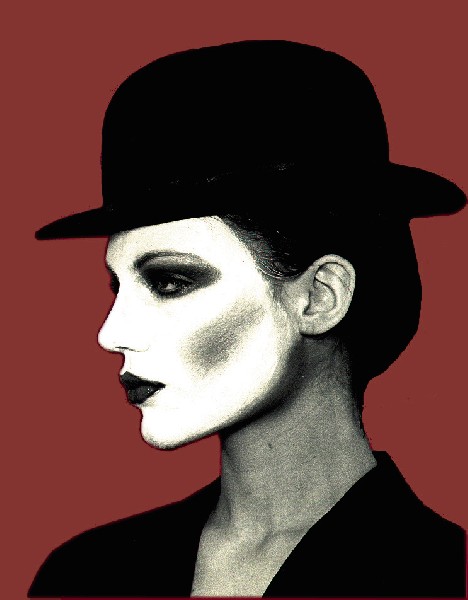

Today, Matuschka would rather discuss her new work that is still being discovered. Work that is not as well-known as the images that became historical, studied by scholars, reprinted in a variety of publications, and occasionally awarded. Having been involved in the environmental and feminist movements of the 80s, Special Education in the inner city school system during the early 90s, and the breast cancer epidemic since 1991, the artist’s focus shifted in 2000 while temporarily residing in South Philadelphia. There she lived on the fringe of the black ghetto and, as her web site points out, racism and the issues of globalization fascinated her.

These observations and emotions lead to “Don’t Globalize This,” whose point was to raise questions about identity, power, and the social concepts of race and gender. She wanted “to bring greater awareness of the effects of globalization in a homogenized culture which explores depersonalization through advertising." So, while it is not a critique of Government policy, it points out a part of American culture that many feel bears criticism.

Like her previous photographic work, this 2000-2001 material focuses on self-portrait, but utilizes a format that incorporates multiple photographic images and text into a unified piece of artwork. The work depicts the model (who is also the photographer) in a variety of settings, with gender and racial transmogrifications (through faux mustache, blackface makeup, and other theatrical accoutrements), “all designed to confuse the viewer into asking what is going on.” The photographs are accompanied by essays or contemplative sayings, such as “one has to suffer a lot to have no more desire,” “if you’re not living on the edge, you’re taking up too much space,” and “everyone has an accent.”

Looking at these photographs makes one think of the message, as well as the work itself, which is, after all, the point of activism. And, the point of art.

Unlike her breast cancer awareness campaign, “Globalize” did not attract much attention, a fact which the artist chalks off to timing. “I came down with ‘the disease du jour’ at the right time and was in the right place [an irony in itself, when you think of it. Ed.]. So my timing was right on and everything worked out.

“But with the globalization series, 9/11 interfered with my agenda. Because this body of work was critical of American culture, it was difficult, in fact, impossible to have the work displayed after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11.”

Unfortunate, because “Don’t Globalize This” is one of the artist’s favorite series whose origin is activistic and more politically driven. “I finished the last image on the eve of 9/11, in fact. The Exhibition opened in New York, and was shown later at the University of Michigan; but this body of work didn’t get many reviews or go very far because it was difficult to criticize America after 9/11.” But there is news on this front: after five years in a sort of exhibition limbo, perhaps the attitudes have changed. “Don’t Globalize This” will be featured in the biennial photo show at the Carrie Haddad Gallery in Great Barrington, early in 2007.

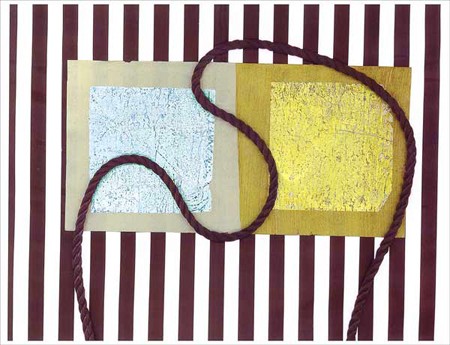

Meanwhile, in 2005 Matuschka returned to her love of abstract work, work that always starts with something physical, something that exists already…something concrete. For example, a simple shopping bag with a kinky rope. She discovered the visual backgrounds were vivid colors with intriguing designs, which inspired her to cover up the logos or any other advertising paraphernalia and make the bag beautiful, scan it into her computer, and output the image onto thick watercolor paper. The result of this process exemplifies an observation that concrete forms can be used to make an abstract result…rather the opposite of how an architect might work.

She recalls Jennifer Bartlett, an abstract painter and former teacher who gave the class another exercise in realism when Matuschka was 20, heading away from figurative, representational work. “It was 1974 and I was really into Cy Tombly and Rauchsenberg and didn’t want to paint another still life. So, I reinvented what Bartlett wanted the class to do”

The work entailed taking small pieces from the environment, showing them out of context (think of cracked floor tiles, an area of a painted wall that has been damaged by chairs. Up close, enlarged, and framed, those realistic elements might become masterpieces of abstract art).

“Ironically, I got the only A.”

Maybe ironic, maybe just a just reward for good thinking.

With her new “In the Bag” project that incorporates digitalization and photography, Matuschka feels a bit as if she’s stepping back into the 70s, a fertile time for both her life and artwork when she took “pieces of life threw them into a bag, and waited with curious anticipation for what would tumble out.” In revisiting the world of abstraction and color she has also revisited her old stomping grounds, the Berkshires. And despite the fact that everybody knows her, it is incorrect to say they know her work, at least her current work.

When Life Magazine declares you as the subject of one of the 100 most influential photos of the century, as occurred with her post-mastectomy image that had been printed on the cover of a New York Times Sunday Magazine issue, it is difficult to leave that distinction behind. But it is part of her activist past—emphasis on “past”-- and Matuschka is ever moving forward. While she still licenses the old images for publication, she will primarily be showing her new work, her new paintings and the Shopping Bag project at the Store Front Artist Space in Pittsfield this fall.

Matuschka and her activistic work addressing the environment and pollutional links to cancer have been featured in numerous documentaries including the Canadian Film Exposure narrated by Olivia Newton John and released in 1998. The artist’s posters (sponsored by W.H.A.M., Greenpeace & The National Lymphedma Network) have been featured in numerous many international publications, plastered in Urban areas, won several prestigious awards and in 1996 “Time for Prevention” was added to the permanent collection of the Cooper Hewit Design Museum in NYC.

Papers about Matuschka's contribution to the Breast Cancer Movement and interviews continue to be published in a wide range of academic journals internationally. Most recently a thorough account of her work with illustrations and feature interview was published by The International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education in their special issue entitled “Constructing Breast Cancer: Discourses and Practices” in 2004.

So, while she is certainly moving ahead, she cannot leave those achievements far behind. Future and past, two more masters, being served equally well by a most accomplished and interesting artist.

Reprinted with the permission of Edward Bride. See her work at Sohn Fine Art in Stockbridge and online at www.matuschka.ne

Matuschka Reacts to Angelina Jolie

Charles Giuliano Interview 2007