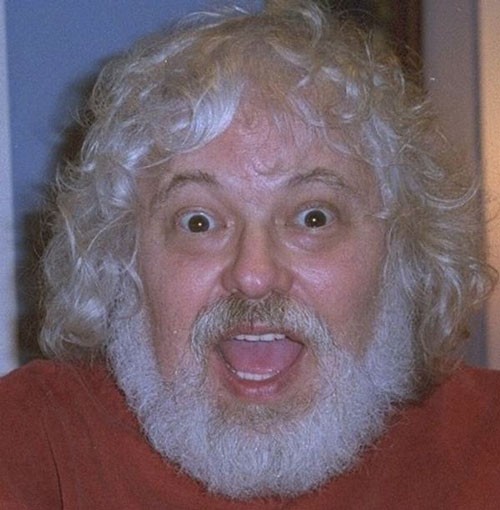

A Conversation With Herb Gart - Part VII

On Auditioning Record Labels

By: David Wilson - Jun 24, 2012

David Wilson Herb, I want to talk a bit about record companies and the recording industry, then and now and get your perspective on the changes that occurred in the latter half of the 20th century. I know that in some ways you were an agent of some of that change. What were some of the changes you set in motion that come immediately to mind?

Herb Gart In The Youngbloods contract with RCA I negotiated a special clause that changed the way artists could record for their labels. I got them to agree to let us have as many 3 hour recording sessions as we wanted as long as there were no more than six musician to be paid in the session. RCA was used to sessions by Henry Mancini and other large orchestras, so it seemed a reasonable request to them. However, there are only four members in The Youngbloods, so we would never have to pay more than 6 people in any session. This meant we could record forever - and we did. The result is that other artists started to demand extra recording time.

DW Pat Sky once told me that Vanguard freaked every time you called to set up an appointment.

HG When I negotiated the Buffy Sainte-Marie contract with Vanguard Records, I was dealing with a very conservative folk and classical music label. ‘Real’ promotion was just not what they did. I had a list of things I wanted them to do, but I started out by asking them for billboards over the Lincoln and Holland Tunnels! This so shocked them, that they gave me almost everything else I asked for as long as I dropped that tunnel idea!

DW I found Vanguard, and really, that meant Maynard Solomon, hesitant to accept opportunities for promotion, although with careful explanation if it made any sense he usually came around.

HG To give you an idea of how conservative they were, I let my great publicist Dan Moriarty go to their office for a day to try to help get publicity for their artists. Dan came back to the office and said that Vanguard was a hopeless case. He had gotten an article in Time Magazine for their esoteric banjo player, Sandy Bull. Vanguard turned down the article because they didn’t think it was appropriate for a folk artist to be in Time!

DW Hah! Ever get a concession from them that came back to haunt you?

HG I negotiated a contract for John Hurt to record for Vanguard Records. There was constant conflict among the people working for John; Dick Waterman, Tom Hoskins and I all wanted to protect John from any harm, so we fought and argued about everything. When I made the contract for John I wanted to be sure for history’s sake, that I got the credit for making the deal with Vanguard, so I had my name added to the contract as “business manager”. Several years later, Adelphi Records, who had a deal with Tom Hoskins to release some John Hurt records decided to sue Vanguard about their releases.

In fact, Adelphi should have sued Tom Hoskins for misinformation and broken promises, but Tom and Adelphi were close friends and Adelphi knew Tom didn’t have much money. So Adelphi, and Tom, sued Vanguard.

They named me as a party to the suit because my name was on the contract! After their lawyers took my deposition, they realized that I had nothing to do with the lawsuit so they dropped me from the suit.

This made Vanguard suspicious, so they added me onto the lawsuit! My lawyer got me out of the suit shortly before the trial went to the jury. Lucky thing he did! Although there was no merit to Adelphi’s lawsuit, Vanguard was represented poorly so they lost and had to pay many thousands of dollars to Adelphi and Tom Hoskins. My desire for proper credit almost cost me thousands of dollars!

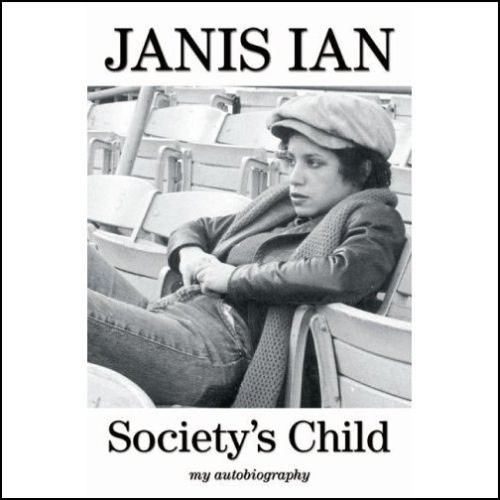

DW In her autobiography, “Society’s Child”, Janis writes very warmly about your efforts to get her a record deal and of taking her tapes to Australia when you went there on tour with Don McLean.

HG When I first tried to get a deal for Janis Ian, I was having trouble getting an American label to understand how much she was worth - so I made my deal with Festival Records in Australia for the recording money and I gave them the rights to Europe and Asia. We had the album almost finished when I walked into the office of Charlie Koppelman, the head of A&R for Columbia. Columbia had turned Janis down twice; once by Clive Davis, then the President of Columbia. and a second time by Charlie Koppelman. “Charlie”, I said. “You can’t turn Janis Ian down, she is too damn good!”

“Okay,” he said and after Columbia Records agreed to sign Janis Ian the negotiations began. At one point I wanted an additional $35,000 in the advance so I took the President of Columbia to lunch at the Keewah Yen Chinese restaurant right next door to the “Black Rock”, the nickname for the Columbia Records building. I had my office right across the street in the building that had been the original Museum of Modern Art before they built the new building. (I finally had to move when the new Museum wanted to tear down the original building to build condos above the museum). I had lunch and dinner at the Keewah Yen almost every day so we became friends. When I took Bruce Lundval to lunch I negotiated about minor things until the fortune cookies were brought at the end of the meal. Then I pressed him for the money and some other important things. When he opened his fortune cookie, the fortune said “Give Herb the deal he wants”.

DW What a great story, did it work?

HG That fortune cookie gained $35,000 and a few extras.

DW Didn’t the record labels ever learn how tricky it was to negotiate with you?

HG The final contract I negotiated for Janis Ian was so complicated, that it was used to teach newcomers to the legal department. We made our deal for the United States and Canada as I had given Europe to Festival Records. Then on behalf of Festival, I negotiated a deal for Europe with Columbia International. To make a long story short, when Janis announced she was recording an album, we received advances from the United States, Europe and Australia!

DW It is still hard for me to understand why artists as accomplished and as fine as Janis Ian and Don McLean were, had such difficulty getting a record contract

HG Why do unique artists have so much trouble getting a record deal? Because they are unique. A&R, (Artist & Repertoire,) men like to claim they are looking for the “next big thing” but they almost always pass on the “next big thing”. There are many reasons for this. First of all, there are only two great A&R men and I can’t think of who the second one is.

DW [sigh]… Go on…

HG Also, being human, A&R men have certain tastes. They can’t be expected to like all kinds of music. If you brought to five different A&R men tapes of Prince, Bob Dylan, The Rolling Stones and Garth Brooks, they would choose one, assuming the others were not worth signing. It is a very rare person who can function well in more than one idiom. More important than all of that, when an artist is unique, they don’t fit easily into any pigeonhole. Since they are not easy to pigeonhole, it leaves the A&R man uneasy. He usually translates this uneasiness into a negative. His career depends on his signing acts that he is certain will sell well. With a unique artist, he can’t be sure. Most great artists have long tales of rejection before they finally find the right A&R man.

I explain to my clients that they are not auditioning for a record company; the record company is auditioning for us. We know you’re great and we are looking for the A&R man who gets it. If they don’t get it, we pass on them. This point-of-view has aided some artists to get through the constant rejection on their way to finding the ONE who hears it and understands it.

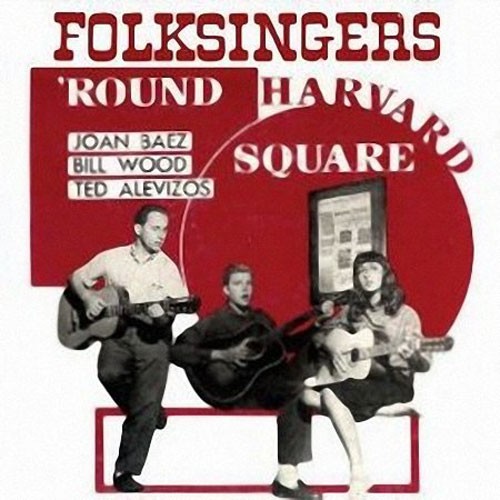

DW A number of years ago I had a conversation with Ted Alevizos. Ted was a lawyer and the head of Harvard’s Widener Library and was on that first LP with Joan Baez, Folk Singers Around Harvard Square. At the time we spoke he was on a crusade to get a number of folk artists the royalties to which their contracts entitled them and he was constantly in the middle of one audit after another. How have you kept record companies honest?

HG As to keeping record companies honest, the first rule is they aren't. Assuming enough sales to warrant the expense, the occasional audit will always turn up some money they 'forgot' to pay. In one case, there was a top record company executive who was known to get paid a piece of the action under the table; I always said that was a good label to be with because you knew that you could always get out of the contract by suing! Keeping track of past deals was not often necessary because my share of the total amount came to me first.

DW Didn’t you have to keep track of sales to make sure your clients were getting their due royalties? With sales of a lot of your artists continuing even to this day, I would think that requires a lot of monitoring.

HG Your only way to keep track of sales in the 60s and 70s was the statements you got from the label. As these were usually ‘inaccurate’ you had to have a ‘feel’ for when to audit. Another way was to hire the Harry Fox Agency who audited the labels for publishing money continuously. Based on their reports, you could get a fair idea of what was in the pipeline. Also if BMI or ASCAP showed significant airplay, it would be a fair indicator that sales were happening.

These days it’s a bit easier thanks to computer software and Neilsen’s Soundscan, a sales tracking service.

DW Someday I would like to have a conversation with you about copyrights, how they have become changed, some would say perverted, through time and how in their pursuit of profit media corporations and their front organizations, the RIAA for example, have destroyed their own market to the point where they are now devouring the very fans who have continued to support them. Clearly that would require a lot more space and time than we have here at this moment. But, I would like to ask you for an off the cuff assessment of the recording industry as a whole and its current decline.

HG The business of music is changing and the record industry has a lot of adjusting to do. They are working on the old model in which they controlled all sales and all artists. They have come late to the internet. The new business model centers around the artist’s business instead of the record companies. They have lost a lot of their control. The business should have always centered on the artist’s business because that is the only way the record companies had product to sell. They are part of a chain that comes from the artist. Radio stations are another one whose influence has been reduced. Those that play records are dependent on the artist creating the records they play. Club owners, concert promoters, and TV shows depend on talent to make their money. Up to a few years ago, all of these people were in complete control of the fate of an artist. Things are changing rapidly. Due to two factors, one being the audio and TV technical improvements: an artist can make a record that sounds as good as any they could have made ten years ago in an expensive studio - they can do that in their kitchen with a few thousand dollars worth of equipment that ten years ago would have cost much more money.

DW That gives the artist more freedom and control over production… What about distribution?

HG The other change is the internet. No artist has to find a label that will sign them nor do they have to deal with the lack of control they face with a Columbia Records. Their work in the kitchen can be put on the internet and have as much chance of success as they would have on a commercial label. Almost all records on Columbia don’t sell well. Almost all records on the internet fail to create enough buzz to succeed, but the possible audience is a lot larger than radio can provide and when you put together something that creates a strong reaction, you are famous across the world. At that point, it may be wise to work with a record company, but the negotiating position you are in is much stronger. One of the advantages to the internet for labels is that the internet can find the strong buzz artists and increase the labels’ chance to get a good return on their investment. The labels could make a lot more money on the internet if they recognized it as an important source of income instead of having the RIAA fight it all the time.

DW Can you give us a concrete example?

HG One example: Before the release of Brittney Spears’ (or some other artist who is currently hot) new single, it can be made available on the internet for one day at 99 cents a download. That could easily bring in more than a million dollars in one day with almost no overhead and help promote the record at the same time. Another result of the internet is that people can choose the songs they want to download instead of having to spend more than $10 to buy the whole CD. This is a different way of selling singles, not albums. The public picks the single -and album sales increases if they like what they hear. I, for one, am grateful that the internet put the music industry back in the artist’s court.

DW So the RIAA (and the MPAA,) are acting as the enforcement arms of a dubious industry strategy, attacking the fan base of the very artists whose product they both need to survive.

HG The RIAA is desperately trying to retain some control for the record industry by ignoring the new business models and trying to prevent people from downloading the songs for free. Yet the label will spend several hundred thousand dollars to get radio to play their song which the listener gets for free. The promotion on radio benefits the artist and the label. The same applies to the internet except that the record company makes less money but the artist benefits more. When an artist is already famous, it is hard to judge the positive impact that downloads have on their careers. It is much easier to judge the impact on a new artist. Yet they both benefit at the concerts and peripheral sales like tee shirts - which often make as much or more money than the concerts!

Record Companies are prepared to spend over $100,000 to get radio stations to play their record and another larger sum to get TV to play their videos. All of this is to send their record out to the public FOR FREE so that the public can HEAR the artist and decide whether they like them or not. The consumer gets the music FREE, then decides to buy the CD or the Single, the one song they like. Record companies recognize the value of PROMOTION and are stupid not to realize that it applies to the internet as well as a radio station.

The same principle applies. CD sales are down because people would rather spend 99 cents to get the song they love than spend $15 to buy the CD. The internet business model is one of single sales and the ability for the public to choose their own playlists at 99 cents apiece. All the free downloads are promotion that is very valuable to the artist in many ways from getting KNOWN to selling tee shirts and tickets; building a fan base and getting a substantial offer from a major label - or making more money selling less product on their own label, since royalty rates with the majors are a rip-off anyway. It is harder to judge the positive value to an already successful artist, but I think there is some value.

So the industry has shifted from the labels to the artist. The labels are still important because they have money and distribution that is valuable and a promotion staff and influence. But they are no longer the only game in town.

**********

Next, Herb shares his regrets about some of the acts he did not get to represent, and some he represented who gang agley...

Videos

McLean - Vincent

A Conversation With Herb Gart – Part I

A Conversation With Herb Gart – Part II

A Conversation With Herb Gart – Part III

A Conversation With Herb Gart - Part IV

A Conversation With Herb Gart - Part V

A Conversation With Herb Gart - Part VI

A Conversation With Herb Gart - Part VII

A Conversation With Herb Gart - Part VIII

A Conversation With Herb Gart - Part IX