Tanglewood Jazz Festival Two

Sing the Truth, Mingus/ Schuller, Cobb

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 07, 2011

The rains came. Before and after.

In between the weather Gods smiled as we managed to scrape through the annual Tanglewood Jazz Festival unscathed under ominous clouds and humidity so thick you could cut it with a knife.

The break of a niche between storms got lots of folks out of the house to dig jazz. Ozawa Hall was packed for afternoon and evening concerts and there was a good crowd on the lawn clustered around the open end.

With charisma and energy during the Sunday evening Sing the Truth, the African singer Angelique Kidjo hopped off stage, charged down the aisle and plunged deep into the lawn crowd. It united all elements of the audience.

There seemed to be a perfect symmetry between a Sunday afternoon that brought us two Jazz Masters. First, Coast to Coast All-Stars, with vocals by Mary Stallings, led by legendary drummer Jimmy Cobb. After intermission we heard The Mingus Orchestra including four selections as transcribed and conducted by Gunther Schuller. Returning from a dinner break the roof of the Shed was blow off by Sing the Truth featuring the Soul Sisters, Kidjo, with four time Grammy winner, Dianne Reeves, and Lizz Wright.

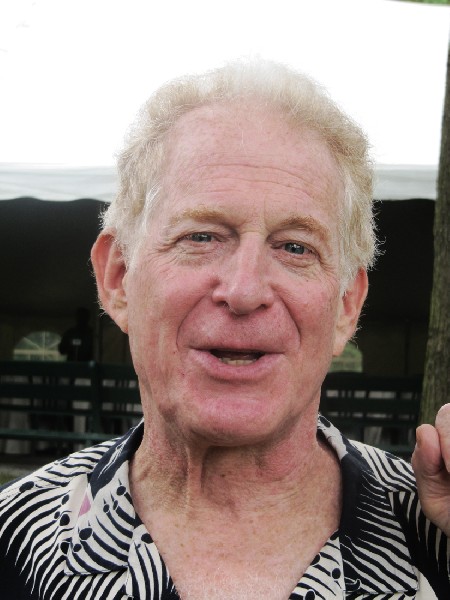

On Saturday afternoon we attended a dialogue conducted by jazz critic Bob Blumenthal. He conversed with the NEA anointed Jazz Masters, Cobb, and Schuller. It was a great introduction for their Sunday afternoon program.

In particular it was insightful to hear Schuller talk about his introduction to American music and jazz. He grew up in Germany during the Third Reich and even revealed that, as a student in a secluded boarding school, he was forced to join the Hitler Youth. Of course American jazz was verboten. He descended from generations of musicians but came to develop a taste that reached beyond classical music.

In 1949 he was a part of the Miles Davis nonet that created a series of 78’s later released by Capitol Records as The Birth of the Cool during the early days of LPs. He discussed a particular interest in the music of Charles Mingus primarily because of a mutual love of “low notes.” In addition to bass, the music Schuller transcribed from 32 instruments to just ten for the Tanglewood concert included bassoon, bass clarinet, and French horn. There is a lot of bottom in the music of Mingus as well as a rich vein of classical influences. Mingus aspired to play bass with a symphony orchestra but came of age when that was not possible for black musicians.

During the Blumenthal led session the three expounded on how the music of so many jazz masters from Scott Joplin, to Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington has fallen off the mainstream radar screen.

As we noted in a review of Porgy and Bess at Tanglewood the first jazz opera Treemonisha was written by Joplin in 1910 but was not fully staged and performed until 1972. Schuller’s book Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development, Oxford University Press, 1968 essentially rediscovered the ragtime of Joplin. In 1973 Marvin Hamlish won an Oscar for his score of Joplin’s “The Entertainer” for the hit film The Sting.

As Schuller informed us Mingus was influenced by modern classical composers from Igor Stavinsky to Arnold Schoenberg including the atonalities of 12 tone composing. It is what informs the music of Mingus making it so rich, complex and compelling.

As an autodidact Cobb developed a unique approach to percussion. With bass player, Paul Chambers, and pianist, Wynton Kelly, as Blumenthal noted they formed the all time great rhythm section with Miles Davis and later with guitarist, Wes Montgomery. Famously Cobb was the drummer for the seminal Kind of Blue Davis album in 1960. From 1955 to 1958 Philly Joe Jones was the drummer with the Davis quintet. Miles referred to him as his “favorite drummer.” When Jones departed Cobb was the drummer for Kind of Blue which was recorded in 1959 and released the following year. While Jones may be more highly regarded Cobb had the right touch for the modal style which emerged at that time.

Cobb participated in the Davis sessions for Sketches of Spain, Someday My Prince Will Come, Live at Carnegie Hall, Live at the Blackhawk, and briefly on Porgy and Bess and Sorcerer. Kelly shared tracks on Kind of Blue with pianist Bill Evans.

With humor Cobb described his style. When playing with Dizzy Gillespie the trumpet player leaned down to hear the bass drum which is kicked using the right foot on a pedal. The left foot of a jazz drummer is used in a similar manner to play the high hat cymbals.

Dizzy wanted to hear his bass kick but Cobb told him that “There isn’t any.” We cracked up at that observation. Instead he demonstrated in the air the technique of keeping a beat on the cymbals. It developed in response to Chambers telling him that Cobb’s bass drum was drowning out his playing.

With gusto and duende Cobb, now 82, discussed how when paired with Chambers, they worked with what the other musicians gave them. A drummer is key to a band. As Blumenthal put it “I would rather hear a bad band with a great drummer than a great band with a bad drummer.” Try to imagine Basie, for example, without the drive of Jo Jones. Or what Benny Goodman sounded like when Gene Krupa departed after the 1938 Carnegie Hall Concert. (Along with Harry James, Lionel Hampton and Teddy Wilson.) Benny was just Bingo after that star studded night when side men from Basie and Ellington jammed with him.

The drummer is so essential that Blumenthal related how, out of frustration, Mingus trained Dannie Richmond. He started playing tenor sax until Mingus convinced him to make the switch. After that they played together for 21 years.

At Tanglewood Cobb fronted a band that included guitarist Peter Bernstein, bass player, John Webber, trumpet, Freddie Hendrix, alto sax, Jaleel Shaw, tenor sax, Doug Lawrence, and piano, Llew Matthews.

The set provided a retrospective of Cobb’s career. They opened with “Say Little Mama Say.” From the Miles Davis era Freddie Hendrix appointed himself brilliantly on trumpet in the Gil Evans arrangement of “It Ain’t Necessarily So” from the album Porgy and Bess. Hendrix provided an incredible simulacrum of the clear, rich, full open tone of Davis. With that same lilting, laid back, laconic and ironic touch. It was so tasty. And recalled the Gershwin opera performance a couple of week ago at Tanglewood.

Channeling Wes Montgomery the guitarist Bernstein was featured on “Full House.” That was followed by the Lucky Thompson composition “While You Were Gone.” For a number of years Cobb has fronted a band called Cobb’s Mob for which he wrote “Cobb’s Groove” featuring the alto of Jaleel Shaw. Then Bernstein came back with his tribute to the great pitcher “Vida Blue.”

For a number of years Cobb was music director for his wife Dinah Washington. He also toured for nine years with Sarah Vaughan. In tribute to that legacy of working with great female vocalists we were introduced to Mary Stallings, a San Francisco based singer. She is a mature and unique stylist who may rightly be spoken of in the same breath with the legends Vaughan and Washington. She offered a three song segment of “I Want to be Happy,” “I Want a Sunday Kind of Love,” and Ellington’s sensual and exotic “Caravan.” The set ended with an instrumental “Tell Me.”

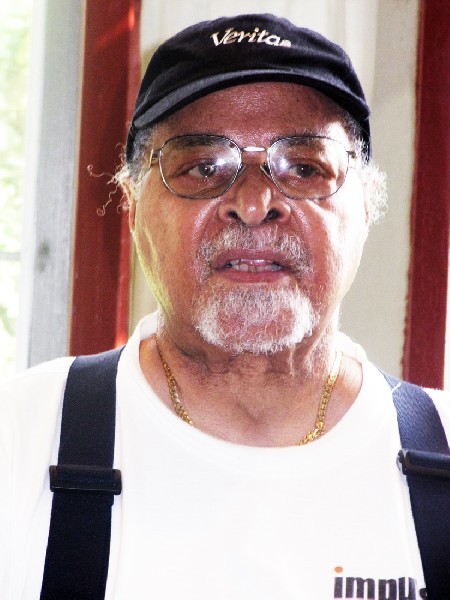

The high point of the weekend was a set featuring ten musicians playing the music of Charles Mingus. While he died in 1979 the music is being kept alive by his wife Sue Mingus. As Schuller pointed out he was so prolific that they are still making discoveries. Some of which came out of the project for Schuller to conduct the two and a half hour long composition Epitaph. From which Schuller conducted brief excerpts.

On ever level, musically, as well as human Mingus was outrageous, obstreperous, over the top, and larger than life. You don’t just experience his music you are assaulted by its joyful, malicious cacophony, infectious rhythms, jungle textures, screams, hollers and ever shifting time signatures. It takes awesomely talented musicians to play such challenging music. Which was surely the case at Tanglewood. Plus the brilliance of a Gunther Schuller to get it spot on perfect in all its splendiferous madness.

It was always a trip to see Mingus during his occasional pit stops at the Jazz Workshop in Boston or during festivals. You never quite knew which persona of his multiple personalities would show up.

For those Boston club dates, for example, he would arrive with Dannie Richman and hire some kids from Berklee. What resulted was a week of open rehearsals. While Richmond kept impeccable time Mingus would rant and rave often stopping and starting the playing while shouting at the cowering sidemen. One fell by as much for the drama and comedy as the chance at hearing great music. It was all worth while when he would make that bass talk, scream, and grunt the blues. He was to bass what Monk was to piano, Davis to trumpet, and Trane to horns. But it takes more than an average dude to dig the bass. Most folks don’t go that low. Mingus was the all time greatest bottom feeder. And hipster par excellence.

During a Carnegie Hall big band gig Mingus lost his place in the score. He just sent it flying with sheet music fluttering in the air. With manic laughter he kept playing and conducting while grooving on the utter chaos.

George Wein liked to get musicians to jam together. During a Boston Garden benefit concert, after his Newport Festival was trashed, all the greats showed up from Mingus and Monk to Aretha Franklin. While Brubeck was playing Wein brought out Mingus. It was hilarious. Brubeck would lay down a riff. When it was his turn Mingus cut it to ribbons. It was like the scene from Amadeus where Mozart with gleeful mischief improvised on themes by Salieri. Mingus had Brubeck for lunch. It was a moment you never forget.

Hearing the great classic “Haitian Fight Song” with all of its anger, frenzy and energy I tried to conjure Mingus. The Peruvian Harp player, Edmar Castaneda, covered for the famous solo opening. It was brilliant, inspired and different. The other musicians included Kenny Rampton, trumpet, Kuumba Frank Lacy, trombone/ vocals, John Clark, horn, Michael Rabinowitz, bassoon, Scott Robinson and Wayne Escoffery, saxophones, David Gilmore, guitar, Boris Kozlov, bass and Donald Edwards, drums.

Mingus wrote “Eclipse” for Billie Holiday. He mailed it to her but never got a reply. I always loved the Jackie Paris version of the song. On this occasion it was sung by the trombonist Kuumba Frank Lacy. Of the great musicians in this ensemble Lacy was particularly memorable for his gritty, guttural, screeching horn playing as well as funky singing. He was also featured on the outrageously comic “Mr. Jellyroll” a tribute to the self described “Inventor of Jazz” Jelly Roll Morton. Lacy ended the set with a reading from “Eclessiastes.”

In between we heard the four Schuller conducted pieces including the early “Half Mast” and the masterful “Inquisition” as well as music from “Epitaph.” In the manner of a New Orleans funeral the musicians ended the program by playing while wandering around the stage to the delight of the spellbound audience.

Out there. Gone man gone.

Having toured extensively in Europe Sing the Truth capped off the Tanglewood Jazz Festival. Rarely have we experienced a more joyful and motivated performance. It demonstrated yet again that the whole, Angelique Kidjo, Dianne Reeves, and Lizz Wright, was more than the sum of its parts. Together the women, who opened with Tina Tunrner’s “Bold Soul Sisters” challenged and inspired each other. Of the three Reeves is the most formidable with a unique position among elite jazz singers of her generation. Kidjo brought a special energy and flavor to the evening. Rounding out the trio Wright held her own. She is a generation younger than the matronly Reeves, or Kidjo, at mid career. Wright does not yet have the depth and life experience of the formidable other women.

The wild card, in every sense, of the mix proved to be Kidjo. Actually, as she was born in Benin in 1960, Angélique Kpasseloko Hinto Hounsinou Kandjo Manta Zogbin Kidjo. She is fluent in Fon, French, Yorùbá, and English and sings in all four languages. She also has her own personal language which includes words that serve as song titles such as "Batonga". “Malaika” is a song sung in Swahili language. She often utilizes Benin's traditional Zilin vocal technique and jazz vocalese.

A petite woman dressed in a richly patterned, long African skirt with an orange top she often danced as well as sang. She spoke informatively and interacted well with the audience. She described how her father introduced her to many different genres of music. From her mother she learned that music is universal and has no nationality, race, or color. It appeals to and is understood by all people. She also made a special tribute to the late Miriam Makiba the best known of modern African singers. “It is because of her that I am on stage today” she said.

The sisters sang songs together as well as separately. The range of material was eclectic but selected to convey the notion of Truth. Another way of putting is was that there was no pop fluff or entertainment bullshit.

In this context it was interesting to hear their take on the Stones’ “Gimme Shelter” or a new meaning to Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now.” Wright’s gospel roots were featured on “Love is Forever.”

The highlight from Reeves was a stunning version of the Tracy Chapman song “All That You Have Is Your Soul.” She strung it out with embellishments that elevated it from a song to an anthem. The audience was electrified by her intensity.

The musicians backing the trio were under the direction of drummer Terri Lyne Carrington with pianist, Geri Allen, Romero Lubambo, guitar, James Genus, bass, and Munyungo Jackson, percussion.

The audience erupted when Kidjo covered the Makiba song “Pata, Pata.” Stating that if she sings in English, not her native language, then the audience owed her one by chiming in with a chorus in her own tongue. After a bit of successful rehearsal she launched into “Mama Africa” then she bolted into the audience.

After that, as they say, the crowd went wild.

What a wonderful way to bring the curtain down on a summer of music at Tanglewood.