Gunther Schuller and Jimmy Cobb on Miles Davis

Birth of the Cool and Kind of Blue

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 09, 2011

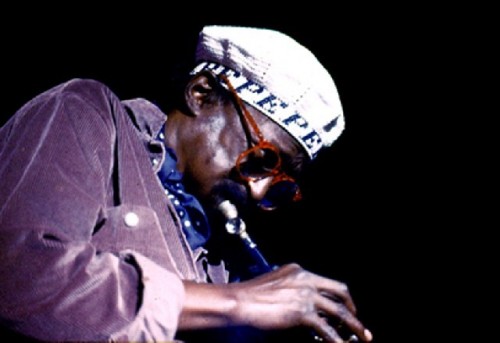

A new feature of the annual Tanglewood Jazz Festival were seminars with jazz critic and historian Bob Blumenthal. On Saturday afternoon he conducted a dialogue with the NEA’s Jazz Masters, drummer, Jimmy Cobb, and composer/ conductor Gunther Schuller.

On Sunday afternoon they shared a program in Ozawa Hall. Jimmy Cobb opened with a set by his Coast to Coast All-Stars featuring the San Francisco based singer Mary Stallings. That was followed by The Mingus Orchestra in a set that also included four pieces transcribed and conducted by Schuller.

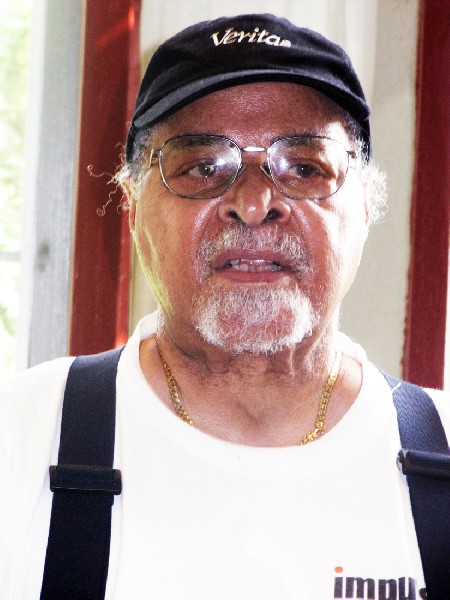

Trained as a classical musician and composer in his native Germany, upon emigrating to the United States, Schuller developed a lifelong passion for jazz. He straddled the worlds of classical music and jazz. When he became director of the New England Conservatory, in the 1960s, he initiated an undergraduate and graduate degree program in jazz. For which he assembled a renowned faculty. It was the first classical conservatory that expanded to include jazz.

In 1955 Schuller and jazz pianist John Lewis founded the Modern Jazz Society, which gave its first concert in Town Hall, New York later known as the Jazz and Classical Music Society. While lecturing at Brandeis University in 1957 he coined the term "Third Stream" to describe music that combines classical and jazz techniques.

He wrote many works according to its principles, among them Transformation (1957, for jazz ensemble), Concertino (1959, for jazz quartet and orchestra; one of its movements, Progression in Tempo, has sometimes been performed separately), Abstraction (1959, for nine instruments), the opera The Visitation (1966), and Variants on a Theme of Thelonious Monk (1960, for 13 instruments), which was recorded by Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, and Bill Evans. He also orchestrated Scott Joplin's only known surviving opera Treemonisha for the Houston Grand Opera's premier production of this work.

In 1959 Schuller gave up performance to devote himself to composition, teaching and writing. He has conducted internationally and studied and recorded jazz. Schuller has written over 160 original compositions.

Boston has evolved as the foremost matrix for jazz education. In addition to the program at the New England Conservatory there is also the renowned Berklee College of Music. It was founded in 1945 by Lawrence Berk as Schillinger House. In 1954 the name was changed to Berklee School of Music and in 1970 it became Berklee College of Music.

The Blumenthal led session with Cobb and Schuller focused on their evolution as jazz artists and the program planned for Sunday. When it was opened up for questions I wanted to know about their connections to Miles Davis on the albums Birth of the Cool and Kind of Blue.

Birth of the Cool is an album released in 1957 on Capitol Records. It compiles twelve songs recorded by Davis's nonet for the label over the course of three sessions. The music consisted of innovative arrangements inspired by classical music, and marked a major development in post-bebop jazz. Blue Note recently released a version using the original tapes from Rudy Van Gelder, who produced the album.

The nonet performed for a two week engagement in late August and early September 1948 at the Royal Roost Club in New York. Billed as the "Miles Davis Band", the group at this time consisted of Davis (trumpet), Mike Zwerin (trombone), Bill Barber (tuba), Junior Collins (French horn), Gerry Mulligan (baritone saxophone), Lee Konitz (alto saxophone), John Lewis (piano), Al McKibbon (bass), and Max Roach (drums). Vocalist Kenny Hagood was featured on a few songs. Unusually, the arrangers (Mulligan, Evans and Lewis) were given credit.

The group returned to the Royal Roost later in September, and recordings from 4 September and 18 September 1948, were included on the 1998 Complete Birth of the Cool CD, alongside the later studio sides. There was a further short residency the following year at the Clique Club. In 1949 Davis had a contract with Capitol to record twelve sides for 78 rpm singles. He reformed the nonet to record three sessions in January and April 1949 and March 1950. Davis, Konitz, Mulligan and Barber were the only musicians who played on all three sessions. Schuller was included in a studio session.

Kind of Blue was released August 17, 1959, on Columbia Records. Recording sessions for the album took place at Columbia's 30th Street Studio in New York City on March 2 and April 22, 1959. The sessions featured Davis's ensemble sextet, which consisted of pianists Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly, drummer Jimmy Cobb, bassist Paul Chambers, tenor sax John Coltrane and alto sax, Julian "Cannonball" Adderley. After the inclusion of Bill Evans into his sextet, Davis followed up on the modal experimentations of Milestones (1958) and 1958 Miles (1958) by basing the album entirely on modality. Kind of Blue is Davis's best-selling album and the best-selling jazz record of all time. On October 7, 2008, it was certified quadruple platinum in sales by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).

Charles Giuliano You were both involved with Miles Davis in recording two of the seminal albums of the 20th century. Last year was the 50th anniversary of the release of Kind of Blue. The sessions for Birth of the Cool occurred in 1949-1950 and you (Schuller) played French Horn with Miles.

Gunther Schuller. No French. Horn.

Bob Blumenthal That’s one of Gunther’s complaints. It’s a horn, not a French horn.

CG Those two albums changed the music of the 20th century. Can the two of you recall those sessions as well as comment on the importance of those albums?

GS For Birth of the Cool there were three sessions in 1948, 1949, and 1950. It was issued on 78s. It wasn’t issued on LP. It was one of the greatest flops in the history of jazz. Gill’s (Evans arranger/ conductor) sound his velvety touch. The extraordinary harmonic language and all these things that he did. This was just too far out and it wasn’t loud. A lot of people like loud, fast jazz but this was subtle music and very quiet. Rich in many colors so it was ahead of its time just like the Lenox School of Jazz (1957-1960).

Then, I don’t know who it was, Lee Gilette who was an A&R man, or maybe Pete Rugolo (composer and arranger). Nine years after the sessions, as I say nobody bought the records, the critics panned it to hell. Oh, and George Avakian (producer for Columbia Records) thought this was some of the greatest music that had ever been produced in jazz. George had left Capitol Records at that time but he told them you’ve got to do something. With Pete Rugolo pushing Capitol he said you’ve got to release this. It’s some of the greatest music.

Somebody came up with the name Birth of the Cool. And you know what they say, “What’s in a name?” It was a huge success (released as an LP) an instantaneous success.

BB In intervening years Miles Davis had really established himself with the public. So people were more prepared to take it in.

Jimmy Cobb Speaking of Miles Davis didn’t Gil Evans work with Claude Thornhill (1908- 1965, pianist, arranger, composer, and bandleader)?

GS Yes, of course.

JC That was the first sound I heard like that. I heard that Thornhill tune “Snowfall” (1941).

GS He did so many others like “Donna Lee” and “Anthropology” and as early as 1942 he wrote a piece “Buster’s Last Stand” which was already mature Gil Evans. That was a great orchestra (Thornhill). The group that played on that recording (Birth of the Cool) was originally called the Miles Davis Nonet. It had trumpet, also sax with Lee Konitz, Bill Barber, tuba, Gerry Mulligan, baritone sax. It is considered one of the greatest classics of modern jazz.

BB In the transition to Kind of Blue. Musicians heard those records when they came out. In California they started creating nine piece bands with tubas and horns. Not with Gill’s finesse but with what John (Lewis) and Gerry Mulligan did. Similarly I don’t know if Kind of Blue was considered to be Miles Davis’s greatest album but that developed over time.

JC Speaking of Gerry Mulligan that big band he had I thought that was a cocktail band. They played so soft I thought that was a cocktail band.

GS He’s one of those (Cobb) who didn’t like Birth of the Cool.

JC When people say I like Kind of Blue I say, I liked Birth of the Cool when it first came out. They ask what makes Kind of Blue so great? I say, I can’t tell you. If I could tell you I’d be rich man. If I knew what they did I’d be doing it now every day.

GS One thing it is, after all the complexities that came into jazz with Bebop, Free Jazz, Third Stream, we lost a lot of audience through that. Then, what it is about Kind of Blue is a much simplified music. By that I don’t mean anything negative. It’s so pure. It’s so expressive and it’s simple enough in structure. It has a lot of repetition. Which enables people to catch on to what’s happening in the piece. It’s so strong in its simplicity. Simplicity doesn’t have to be something boring or lesser. I think that was the miracle of those tunes.

JC As I tell people if Miles had known that record would be as hip as it is, fifty years later, he would probably own Columbia Records. Because that day he would have asked for four Ferraris.

BB In his autobiography he talked about country, visiting his grandparents and that he wanted to make a blues album. With a different sensibility. He felt that he had failed in terms of what he had heard when it came out.

GS That album was the first time that most people heard the new Miles Davis. The soulful, warm, rich playing and technically, not too much. His using the Harmon mute. That was a whole new sound at that time. Harmon mutes had been around but this velvety, singing quality that he produced, that caught people.

BB I said this to Jimmy before. I don’t think Jimmy gets enough credit for that album. There’s an aura to it. Philly Joe Jones is a great drummer. Not to take anything away from him. But I can’t imagine Philly Joe playing on Kind of Blue. It would have a completely different feeling. If you go back to the way Jimmy, Paul Chambers (bass) and either Wynton Kelly or Bill Evans (piano) mesh in there it just envelops you as a listener. It ties all the solos together in a way that is very different from what had been happening with rhythm sections.

JC When we were doing those big band things (Sketches of Spain, Porgy and Bess) Miles would come over and whisper to me “Make it sound like it’s floating.” I would say, “Ok.” Then Gill would come over and say “Floating is all right but keep the band together.” Everybody is sitting around away from each other and I’m sitting in a place (booth) where you can just see the top of my head.

CG You were separated? What was the reason for that?

JC The engineer knew the exact spot for the exact instrument to sound best. So it was set up that way.

GS That’s not entirely true. I made recordings in that studio for 25 years. This also had to do with that they called quadraphonic sound and the beginnings of multi track recordings. What they wanted us to do, and most of us refused, was to put cans on, headphones. To play that way and most of us refused to do that.

Another reason is that Columbia had not given enough time and money to record Porgy and Bess. We had only four sessions while Sketches of Spain had many more takes for example. We were so unhappy. We would play and knew it really wasn’t perfect. They said “Ok, next tune.” So we went through all of that. Cal Lampley, the producer, figured out that given how little Columbia provided to support this project he would have to do a lot of editing. He spent four or five weeks of editing all this stuff. Yet some of it was so bad he couldn’t get it clean. That was the idea. When you separate all these different groups (of musicians) by fifteen feet, you have a better chance of no leakage into the other tracks. That was one of the main reasons and I never forgave him for that.

JC The reason they put the drummer in a booth was because it would feed into all of the other tracks.

GS It’s terrible because you hear this music and you can’t even hear what you’re playing. Unless you take one ear off the head set.

(In 1953, pianist George Russell published his Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, which offered an alternative to the practice of improvisation based on chords. Abandoning the traditional major and minor key relationships of classical music, Russell developed a new formulation using scales or a series of scales for improvisations. His approach to improvisation came to be known as modal in jazz. Davis saw Russell's methods of composition as a means of getting away from the dense chord-laden compositions of his time, which Davis had labeled "thick". Modal composition, with its reliance on scales and modes, what Miles considered, "a return to melody."

In 1958 Davis remarked on the modal approach. “When Gil wrote the arrangement of ‘I Loves You, Porgy,’ he only wrote a scale for me. No chords... gives you a lot more freedom and space to hear things... there will be fewer chords but infinite possibilities as to what to do with them. Classical composers have been writing this way for years, but jazz musicians seldom have.”

Davis began using with this approach and his sextet. Influenced by Russell's ideas, Davis implemented his first modal composition with the title track of his 1958 album Milestones, which was based on two modes. Instead of soloing in the straight, conventional, melodic way, Davis’s new style of improvisation featured rapid mode and scale changes played against sparse chord changes. Davis' second collaboration with Gil Evans on Porgy and Bess gave him more room for experimentation with Russell's concept and with third stream playing.)