Modern Art in the Berkshires

Clark Curator David Breslin Part Two

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 12, 2014

Charles Giuliano Other than an iconic work like Pollock’s Lavender Mist by far the most astonishing painting in the exhibition was the Guston (Untitled, 1964, oil on cavas, 66 x 76” Gift of Musa Guston). That Guston floored me.

The question is where does it belong. While abstract it is more evolved than his earlier, more modulated, lyrical paintings from the height of Abstract Expressionism. The brush stroke is bigger, bolder, more energized and gestural. It seems closer to the figuration that developed in his later work. This painting seems to reside on the cusp between abstraction and his return to the figure. It’s just a knockout picture.

David Breslin You’re exactly right which is why we chose to use that quote which Amy (Sillman) read at the end. “We are image makers and image ridden.” To frame what we hoped would happen in that symposium. These hinge figurers, these hinge works are great ones to think of what the stakes are. Not just in the period. Individual careers. The fact that people wouldn’t talk to Guston. They wouldn’t talk to the guy after he did his first Klansmen exhibition.

There are real stakes to this. You see it in the painting. Things are being worked through. In the center towards the bottom there’s that little vertical line of almost orange red which reads just as a line but could also read as part of a cigarette referring to pieces that come after.

CG Did you write the catalogue entry on the Guston?

DB I did.

CG I read that and looked intently at the illustration and said where the fuck is the cigarette? (laughing)

What concerns me, as I tried to evoke a comment from Bois, there are the now iconic individuals and monuments. But in an art history that celebrates the victors of the art wars so much falls between the cracks. So many individuals and movements have been swept over in the dominant narrative of Post WWII art, The Triumph.

The neglected movements interest me. But then artists and critics align into camps like figurative vs. abstraction. You can’t be a servant to two masters or many masters. As I was discussing winners and losers with Brice the notion of Red Sox vs. Yankees emerged. You are loyal to one team or the other. It was funny as he put it but also true. That was the way in which the extremes of art making were debated. There were winners and losers.

Unfortunately I have always lined up with the losers. I’m always more interested in what falls off the edge. Which is more interesting to me than yet another book and exhibition on Jasper Johns or Andy Warhol. Or Jeff Koons.

(Marden commented on still trying to make up his mind about Koons. “It’s not for lack of information” he said.)

Perhaps you can help me.

DB I will if I can.

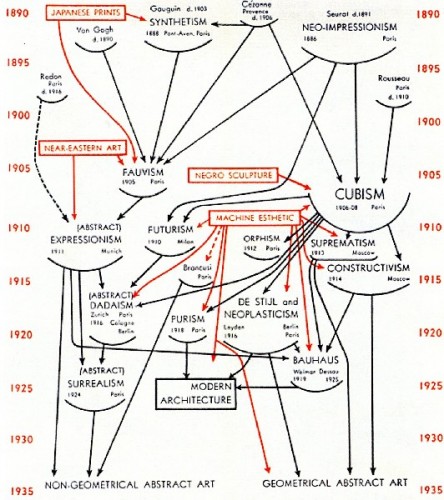

CG In his conversation with Marden it stared with Vincent Katz projecting a diagram delineating the development of schools of abstraction evolving into primary branches. A gestural approach coming from the Abstract Expressionism of Kandinsky. Then a geometric evolution from Constructivism and Mondrian to Ellsworth Kelly.

It was an illustration of the cover of a MoMA exhibition. I would love to see it again. Can you recall it?

DB I believe it was an exhibition that (Alfred) Barr did in 1936.

CG Cubism and Abstract Art?

DB Yes. That’s it.

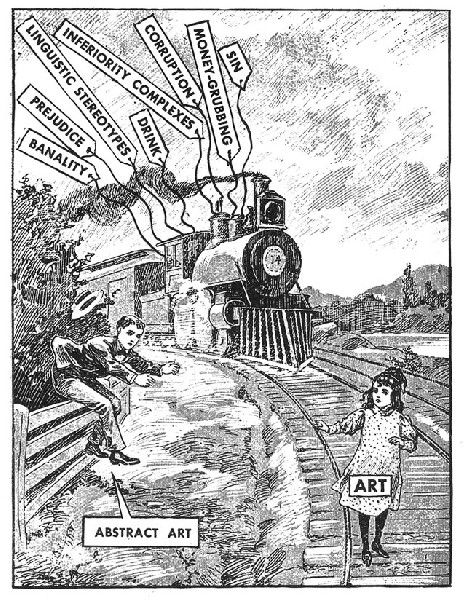

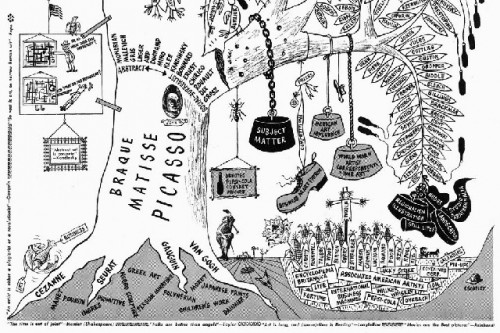

CG Related to that I have always loved the Ad Reinhardt cartoons about modern art. Like the girl on the railroad tracks threatened by an oncoming train. Abstract art is jumping over the fence to rescue her.

There is the fascinating contrast between the witty illustrations and his dauntingly difficult, closely valued paintings that anticipate Op art and Minimalism. Then fast forward to Mark Tansey's representational paintings that illustrate Guilbaut’s idea about the “surrender” of the School of Paris to New York.

I find all that interesting. Do you?

DB We could discuss Reinhardt. How many weeks do you have? (laughs) He kept those two parts of his life always in his brain. They were always kept separate. After him artists decided whether they wanted to keep their advocacy and art in two different planes or bring them together. When do we bring them together? He has been an interesting example.

This would be an interesting question to the Marden comment that “De Kooning taught us how to paint but Pollock taught us how to be artists.” Reinhardt might serve as one of those figures. That’s an interesting question today. I should have posed that to the younger artists up there (at the symposium).

In some ways he thought that you can do it all. But obviously he didn’t or he wouldn’t have had such an engaged life as a cartoonist, caricaturist advocate.

In ways we saw the artists on the stage trying to reconcile how their art can do the things at once that Reinhardt kept separate.

(Glenn Ligon for example projected examples of his porn drawings and Sillman who opted not to illustrate her discussion mentioned jokes as an aspect of the work. Which is a theme with other artists. Is this poetic irony or truncated social commentary?)

In that way he’s extremely instructive and important.

You know, I’m with you. I’m always trying to think through who got left through the cracks.

One of the artists I have worked on for awhile and have always thought about is Paul Thek. (November 2, 1933 - August 10, 1988 an American painter and, later, sculptor and installation artist.)

CG I love his work. Do you remember his Hippie Funeral (Tomb: Death of a Hippie, 1967).

DB When I was in graduate school Harry Cooper supervised my master’s thesis on Paul Thek. I published an essay in the catalogue of the Whitney retrospective a few years ago. It was about the painting he was making just before the Meat pieces. It plays on minimalism. He’s a figure who was extremely smart about the work that was happening in his time. But never fit neatly into any category.

That’s why it’s up to us, Charles, to keep thinking about these people.

I kind of throw out the winners and losers. There are winners and losers around a period. I hate this long run stuff because you like to see people rewarded during their lifetime. For being smart and taking tough points of view.

Thek for me is a big winner. People ignored him because he never changed from being confrontational in the work. He never bowed to market or critical pressures.

CG I reviewed that show (Tomb: Death of a Hippie).

DB I didn’t see that.

CG It was for an underground paper The Avatar. I was the New York correspondent.

(Also wrote in the 1960s for the former Arts Magazine and 57th Street Review a zine published by Betty Parsons Gallery.)

That work floored me and I have often thought of making a funeral piece for myself. In the woods behind our home in the Berkshires. Kind of like a Native American spirit platform with offerings. I was an intern in the Egyptian Department of the Museum of Fine Arts and have long been interested in funerary art.

I agree that Thek is one of the great undervalued artists. But I found the Whitney show strangely disappointing. Something felt missing. It didn’t come through as strongly as it might have.

DB He’s so tough. There’s so little of the environments. You know the story as well as I do. How do you recreate things that were just a part of the magic of what Thek could do. With collaborators some place. Talk about the risk of being truly antiseptic. If you try to recreate an artist’s environment. An environment by an artist who didn’t have a scripted way in which it is installed. More like I’m there for a week give me a ton of chicken coops and newspaper and I’ll do the rest.

The Whitney had some tough calls to make. They were formal calls. There were ethical calls too. What do you do in the name of an artist? What do you do in the name of a curator? I think they took the side that (pause and thinking) Thek wasn’t a conceptual artist. He was really an artist who was dealing with materials. So restaging his stuff would really be a restaging and wouldn’t embody the artwork that actually is or was.

We could talk for hours about that and it would be a really good conversation.

CG Let’s get back to the exhibition and my notion of why it’s antiseptic. First it’s limited to works owned or loaned to the National Gallery. Because it doesn’t own a signification example de Kooning is excluded. Ok. Pollock and de Kooning are the twin peaks of their era.

DB We didn’t exclude it (de Kooning) we just didn’t have one.

CG You could have borrowed one.

DB Could have borrowed one. (pauses) That’s a good question. We were working with the collection of the National Gallery and the few works we did borrow came from living artists. Or had been on long term loan to the National Gallery. Not to make excuses but it was really an exhibition of works from the National Gallery. If we started borrowing things hither and yon it would have been a much different show. You’re exactly right.

CG The jewel in the crown is Pollock’s Lavender Mist. What if the exhibition had included de Kooning’s Excavation (1950, Art Institute of Chicago)? The essay states that subsequent artists primarily evolved from Pollock or de Kooning. Because his technique was so unique essentially Pollock was beyond imitation. If you worked like Pollock it was still a Pollock. When Chuck Close spoke at the Clark he recalled making a hundred De Koonings before coming to his own mature work.

During my student years I made some de Koonings and even a couple of Pollocks. It was a rite of passage for my generation of art students.

DB Glenn Ligon remarked that he made some as well.

CG Talk to me about the twin peaks of Pollock and de Kooning. If we go back to the MoMA diagram of abstraction on one branch it’s gestural from Kandinsky to Joan Mitchell. From the other branch it descends into formalism and the geometric. From Malevich to Elsworth Kelly. Or Robert Ryman. In his work it’s less obvious to assign him as a descendant of one or the other branch.

How do you see that as either or? The panelists appeared to struggle with that dichotomy. They were contemplating origins in the emotional and gestural or the purist and philosophical.

DB I’m wary of Barr’s diagram. It’s an interesting historical document. In some ways if you look at it now it looks like a corporate flow chart. It talks about one thing in the world. In red it has Negro Sculpture or craftsmen from Africa seen in Paris by artists like Matisse and Picasso. There are things like what Brice was talking about, the calligraphic. You have things like Japanese prints which are included in that chart.

The world isn’t represented and we shouldn’t expect Barr’s chart to show the world. When you have generations which Ligon and Eggerer are coming from there’s more knowledge of what’s been happening elsewhere. I hate to use the word phenomenon but abstraction has been a global event. Marden was exactly right and spot on to talk about that its transhistorical and that it’s transnational. That inability to talk about where one comes from is because it comes from a lot of places.

This kind of either or thing that pulls a lot of things in is what keeps curators having a job. Charles, it keeps critics writing. We’re the ones who can help see where these ties are coming from. From our own purview try to see if these strands tie into something neat or they’re as messy as the artists you describe that their influences leave them to be.

CG Can you talk about the chauvinism and jingoism of the abstract expressionists and how that filters down? Ideas like Rosenberg’s American Type Painting and Coonskinism. He used the analogy of Americans during the Revolution as guerillas behind trees picking off the orderly British lined up in an open field. For him the post war American artists were hit and run rebels. There is the rhetoric about how Pollock rejected Cubism. Cooper’s essay coments that de Kooning, an immigrant compared to Pollock (from Cody, Wyoming), never abandoned Cubism which is evident in the structure of his painting. (Greenberg viewed de Kooning as lesser to Pollock for never abandoning figuration.)

The essay talks about Cy Twombly and how he moved further away. (While spending much of his career abroad.) It’s interesting that this show focused on American post war abstraction includes a few relative obscure European artists. (Other than Jean Dubuffet)

DB You’re getting to the heart of whether there is chauvinism in the work or the language of the abstract expressionist artists themselves or is it something that has been written into the work by critics and art historians after. I think there really was an idea that whether it’s chauvinism or just a need to assert what a new tradition of painting would be after, say, Picasso. I think that was very real. When Cooper tries to put Pollock in the place, or younger artists after him, as Picasso was for him. I see it less as a jingoistic thing than a Freudian killing the father issue.

There has been lots of discussion after the fact about the romance of the artist. Anything that strikes of the unconscious will always say, well, isn’t that kind of ridiculous. One feels that he has access to something new, raw, untouched. Whether I buy that or not is another question. To go back to Marden again, what’s art about? It’s about expression.

I don’t think any of the artists on the stage that day would refute, no matter how many references you feel flow through your particular work, you are making those decisions. The idea for me that one can nullify expression is pretty ridiculous. Even what Bois was saying at the end about content. Even if you say there is no content that’s a statement about content. If you say there is no expression or emotion there is expression or emotion.

I guess I wouldn’t want to be so fixed on the idea that the paintings or the work of the period was so chauvinistic. (deep inhaling breath) Or jingoistic. They were really trying to think through what had come before them. And reimagine what it could be. You had these towering models before.

CG This exhibition represents a major change of emphasis for the Clark. What will it mean for the Berkshires? We have a world class venue for contemporary art in Mass MoCA. There’s a think tank in the Williams College Museum of Art. If the Clark goes further in this direction it seems like we’re connecting the dots.

Conforti is careful to say that the Clark doesn’t want to overlap other institutions and their mandates. I see it more as a synergy that can pull institutions together. This creates a visual dialogue that can be very meaningful. Not just to the region but to the field. Because the Clark has the resources to work with and offer residences to top scholars, artists and curators in the field. A vivid example of this is having Cooper organize this exhibition and write a catalogue that brings new thinking to the artists and era in question. It is making us take another look at things we thought we knew.

Where do we go from here?

DB We have a real chance to be as collaborative as possible with our neighbors. The fact that Mass MoCA works with living artists and frequently does things by commission entailing projects that couldn’t be held in many other places. It’s not something we can do or want to since they do it so well.

It’s a matter of articulating what we do well and do best. In that regard the Make It New exhibition falls within a line of carefully researched, hopefully beautifully executed exhibitions that tell a particular story about the history of art. While the subject matter and period in which it was done are different it isn’t far away from how we’ve done business before.

That being so the fact that we can dip our toe into the 20th century and think about that as a historical period allows us to tell a greater story throughout the region. Especially with our friends and neighbors in the area of what the 20th century was. And how it still is in the present.

CG Thinking of the Clark’s campus Conforti during the opening of the renovated museum discussed how artists were coming in with projects to work with the nature trails. He discussed Janet Cardiff and James Turrell. This opens the possibility of creating site specific works. Has anything come from those visits?

DB You’re exactly right and on it in picking up from Michael the direction we might go in when working with living artists and that would be in the landscape. But I don’t think you would ever see trying to be something like a sculpture park. But rather how do we bring in artists to treat the landscape as a living thing as it is and not just placing sculpture as something to be encountered by a viewer. But to have things that don’t even have to be material.

The Cardiff things are walks that would take you through the campus but wouldn’t actually have a physical imprint on it.

I think you’re exactly right. That’s the direction we will be going in. Turrell has been discussed. Cardiff did visit. We’re talking with the German artist Thomas Schütte about a potential project.

All these things are kind of information. As you know the Clark has such a particular mission. When we take on something new we want to do it in a serious and deliberate way because that landscape is very important to us. We don’t want to start dropping things on it because it’s pretty perfect as is. Decisions will be taken seriously. How we articulate that to our public is important to us as well. Why are we doing this if we have peers in the area that do this well?

Historically there has been a sense that good fences make good neighbors. In some respects that is true. Let people have their institutional identities. In being somewhat different from each other we create this cluster of interest.

There’s also room for having some overlap. Missions that can dip into and out of each other create certain synergies that are good for all of us.

Part One of David Breslin interview.