Letter #4 from Southern California

Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980

By: Patricia Hills - Apr 20, 2012

Letter #3 described my visits on Saturday, January 7, to the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, which held Pacific Standard Time exhibitions in both downtown San Diego and La Jolla, on the subject of “California Light and Space.” The next day my son Brad and I drove up to Newport Beach to see the PST exhibition “State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970” held at the Orange County Museum of Art. Organized by both the Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA) in Southern California and, in Northern California, the UC/Berkeley Art Museum and the Pacific Film Archive (BAM/PFA), the curators are Constance M. Lewallen from BAM/PFA and Karen Moss at OCMA.

The curators divided the big exhibition, broadly defined as California Conceptual art into eight themes and idea sets: “Mapping the environment,” “The Street,” “Politics,” “Private and Public Space,” “Feminism and Domestic Space,” “Perceptual and Psychological Space,” “The Body and Performance,” and “The Artistic Process, Language, and Wordplay.” As Lewallen and Moss comment in the accompanying catalogue, in the 1960s California artists played a large role in the development of Conceptual art, “However, during the succeeding decades, the group of artists identified with the beginnings of Conceptual art was narrowed, and, with a few exceptions, California Conceptual artists were less likely to be included among them (p. 3).” Their words echo what I noticed about the California Light and Space artists. East Coast, where were you? Answer: Exhibiting East Coast Regionalism!

(Relevant disclosure: I lived in California as I was coming of age—all through college and then San Francisco for over two years, before my ex-husband and I decamped for New York City to make our fortune. My best friends stayed in the Bay Area and became Buddhists.)

It is easy to see why artists gravitated to California: the weather, easy living, access to good colleges and art schools, music and Fillmore West, liberal politics on campuses (the Free Speech movement), tolerance of hippie and gay life styles, the Beats, the Buddhists, later the Black Panthers. In California one could think and meditate, and no one thought you were weird. Then there were always the mountains, the desert, and the ocean. No wonder artists turned away from the materialism of the object. As Lewallen and Moss observe, “If the object was not eliminated altogether, it was deemphasized in favor of the idea and the process that went into its making. Artists devised new, noncommercial forms of expression and communication: the photographic document, video, sound, performance, and installation—modes that pervade artistic practices today” (p. 2). It seems as if these California artists were ahead of the game.

There was a lot to read in this exhibition: wall labels explaining movements, galleries, exhibitions, networks of artists, etc. Maybe too much to read. As for the artworks: some were familiar from East Coast exhibitions and fun to see again; others, unknown to me, caught my attention and seemed central to the overall themes. I was chiefly struck by the wit and texture of much of the work.

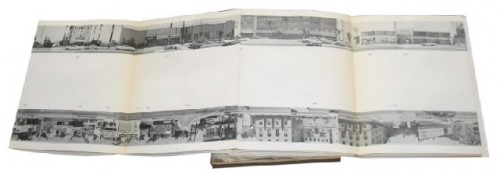

John Baldessari’s California Map Project Part I: California, originally done in 1969, is a witty comment on making concrete what is, after all, a conceit. Baldassari took a map of the state of California and noted the location of each letter on the map. He then traveled from south to north with friends, found the actual geographical spot where each of the letters of CALIFORNIA had been printed on the map, constructed a letter to place on that landscape site, and photographed the result. Since childhood I have always loved not just maps but charting the road trips of my Army family as we criss-crossed the country seeking my father’s next post. I always delighted in imagining and then seeing the towns, rivers, and lakes noted on the maps. Baldessari’s whimsical geographical epistemology thus touched a chord of memory.

Mapping also formed the inspiration for Douglas Huebler’s Duration Piece #9, Berkeley, California—Hull, Massachusetts, January – October, 1969. He executed the piece by mailing a package through the mail to undeliverable addresses, getting the package back by return mail, and then mailing it to another undeliverable address along a plotted route. The final exhibition consists of the battered package (about 3 x 5 x 3 ½ inches), an array of framed receipts, a map, and a typed explanation. With my recent experiences of vexatious relationships with the USPS, I found the piece amusing and almost visceral. One imagines the well-traveled package (what was in it doesn’t matter) going back and forth, handled by endless people, going through sorting machines (if such machines existed in 1969), and finally arriving back to the artist like a good prodigal son.

Mapping is also the motivation of Ed Ruscha in his 1966 artist’s book Every Building on the Sunset Strip, a piece made when Ruscha mounted his camera on the back of his truck and shot every building as he drove along. Then it was a novel idea to photograph buildings adjacent to each other along the streets; today we can get such street views of almost any neighborhood on Google Maps. So such projects have lost their novelty, but not their sociological interest.

All three artists—Baldassari, Huebler, and Ruscha—seem to consider mapping as a way to merge the boundaries, both physical and psychological, between space and place, the body and the mind. One more artist person of interest: mapping guided Bas Jan Ader when he composed his work In Search of the Miraculous (One Night in Los Angeles) of 1973. He took eighteen photographs at regular intervals one night as he walked from the Hollywood Hills through Los Angeles to the Pacific Ocean, passing by stores, highways, and lonely people. The finished work consisted of these photographs mounted on four panels with a handwritten text in white ink scrawled along the bottom edge of the photographs. According to Lewallen’s catalogue essay (p. 28), Ader’s texts were phrases “from the Coasters’ rhythm-and-blues ballad ‘Searchin’.”

Ader’s piece points to the underlying philosophical dimensions to mapping. Unlike Brassaï’s Paris by Night (published 1933 as Paris de nuit)—those great photographs of the streets, storefronts and brothels of Paris and which still charm for their noir sensibility and iconography—Ader’s photographs suggest not the voyeur, but the lonely seeker of some kind of fulfillment.

Mapping guides us to find that place (the destination) through the comprehension of space (the process that needs to be traversed to arrive at the destination). With some this is a game; to others it is deadly serious—a way of knowing. Ader’s photographs have a haunting quality that pulled me in, and I emphasized with the solitary Ader, walking alone at night, not knowing what he would meet, but knowing that when he reached his destination it would be day break. The catalogue tersely describes Ader’s brief career: “In Search of the Miraculous was to be the first of a three-part work. The second was to cross the Atlantic in a small boat; the third, to walk through the night in Amsterdam. He did undertake the ocean voyage in 1975, but was tragically lost at sea” (p. 28). And that is it! Not even a speculation about the circumstances of his death. I can imagine a dissertation here.

Other artists in the exhibition focused on not just the human body, but “performing the body”—making the artist’s own body teach us about stasis and process, about knowing our world phemenologically. In the 1970s, many women artists challenged ideas of female stereotypes as they sought to exercise control over their own representations. Beset always with others’ expectations, they created their own subjectivities from their experiences with their bodies. Eleanor Antin did this literally with her (now famous) Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, 1972. This performance piece consisted of dieting to reduce her weight by ten or so pounds; her documentation consisted of views of her nude—front, back, left side, right side—a total of 144 black-and-white photographs taken over 38 days. Did she lose weight? Perceptible, but only slightly. Her idea was to control her own representation from the inside, so to speak.

Bonnie Sherk in her Sitting Still Series, 1971, defined her art as a performance piece, which entailed moving a chair from place to place, sitting on it, and having someone photograph her in such odd places as the pedestrian lane over the Golden Gate Bridge. Her Public Lunch was another performance where she sat eating lunch at a table set up within a cage in the Lion House at the San Francisco Zoo, seemingly oblivious of a real tiger lolling on a ledge in the adjoining cage. The photograph documenting the event includes visitors’ gawking at her rather than the tiger, as she performs the mundane routine of eating lunch in the context of potentially incipient dangers.

Another meal scene we saw before (see Letter #2) was the photograph documenting the 1974 performance of the Asco group (Gronk, Patssi Valdez, Willie Herrón III, and Harry Gamboa, Jr.) called First Supper (After a Major Riot). In her catalogue essay Karen Moss points out that “Artists who ‘took to the streets’ followed the Situationists’ strategies of disruption and intervention within public space, staging events that responded to particular social issues” (p. 168). In this case the Asco artists were reminding their viewers that a police riot against Latinos had occurred at that corner of Whittier Boulevard on January 31, 1971, which had “turned deadly.”

Other old favorites of mine at OCMA included the 1967-72 photomontage series Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful by Martha Rosler. One shows a “typical” housewife vacuuming in doors while combat images of the Vietnam War can be seen through the window as the curtain is pulled back. Rosler’s political works always depended on “heightening the contradictions,” as admired by activist Marxists.

After spending a couple of hours in the Orange County Museum of Art, Brad and I drove to the Pomona College Museum of Art. There we met my friend Frances Pohl (author of Framing America, a popular textbook on American art), and viewed the show It Happened at Pomona: Art at the Edge of Los Angeles, 1969-1973. This exhibition is actually three consecutive shows that focus on the curators Hal Glicksman and Helene Winer who brought cutting-edge art to the Museum from 1969 to 1972. On view for the second show, which we saw, were early works by John Baldessari, Chris Burden, Allen Ruppersberg, William Wegman, the hapless Bas Jan Ader (who needs the dissertation), and others.

Frances then got some official to open the Pomona dining hall, then under construction, for us to view Orozco’s magnificent mural Prometheus, itself a justification to visit Pomona. The less-well-known murals by Rico Lebrun murals on the theme of Genesis, were hiding behind the arches to a staircase in another part of the campus. According to the Museum’s website, the artist wanted to show the “beginning of form”; the result is imposing, but rather histrionic and confusing. Even Peter Selz, the West Coast critic, curator, and art historian, who always had a predilection toward expressionism, could not muster much enthusiasm. In the one sentence Selz offered the website, he said of Lebrun: “By and large, he stands as a controversial and solitary figure, and the Genesis mural, a religious painting created during a non-religious age, remains a unique act."

Frances, Brad, and I then strolled over to the “Skyspace” structure of James Turrell, a Pomona alumus, who had installed “Dividing the Light,” light show combining artificial and natural light. This is an outdoor space [http://www.pomona.edu/museum/collections/james-turrell-skyspace.aspx] where we sat on a bench that wrapped around a square space over which seemed to float a roof with a large square hole that gave a view of the sky. Twenty-five minutes before sunset, lights go on to illuminate the underside of that roof structure. As the lights change through the colors of the rainbow, they contrast with the steady, ever-deepening colors of the sky. Again: colored light and space transported us away from the mundane and into the sublime. The light show (artificial and natural) lasted for an hour. Ah…Lala Land! What a nice way to end the day.

Back to LA late that night with plans to tackle the “Geffen Contemporary” the next day. That will be the subject for Letter #5.

© Patricia Hills, 2012

Letter Number One